IRVING PENN: BEYOND BEAUTY

Interview by Dustin Mansyur | Photos by Irving Penn

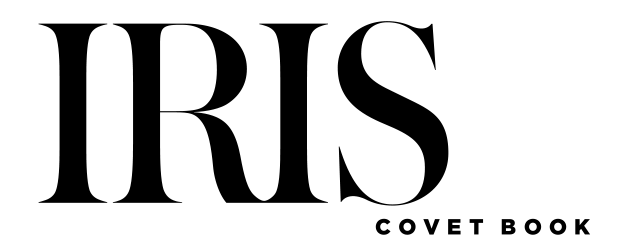

Bee, New York, 1995 by Irving Penn

A discussion with Sue Canterbury of the Dallas Museum of Art on the iconic American photographers latest traveling retrospective in nearly two decades.

For the first time in nearly 20 years, a retrospective of iconic American photographer, Irving Penn, will be on display at the Dallas Museum of Art for the first installment of the Smithsonian American Art Museum-organized (SAAM) exhibition. While known and beloved by fashion for decades, the exhibition delves into the body of Penn’s work, exploring the full range of his career. Often overlooked early periods of the 1930s street scenes & his study of the American South in the 1940s, these earlier works were crucial in the development of Penn’s approach surrounding his lifelong endeavor to experience and create beauty in all subject matter. The exhibition, now on display at the Dallas Museum of Art through August 14, 2016, debuts 100 photographs recently donated by The Irving Penn Foundation with over 40 more additional images drawn exclusively from the Smithsonian’s holdings.

“While Irving Penn was one of the key photographers of the 20th century, this will be the first retrospective of his work in 20 years…His mastery of lighting and composition, and his technical prowess in the darkroom, reveal him as a true master of modern photography,” said Sue Canterbury, the presenting curator in Dallas for the exhibition and the Pauline Gill Sullivan Associate Curator of American Art at the Dallas Museum of Art.

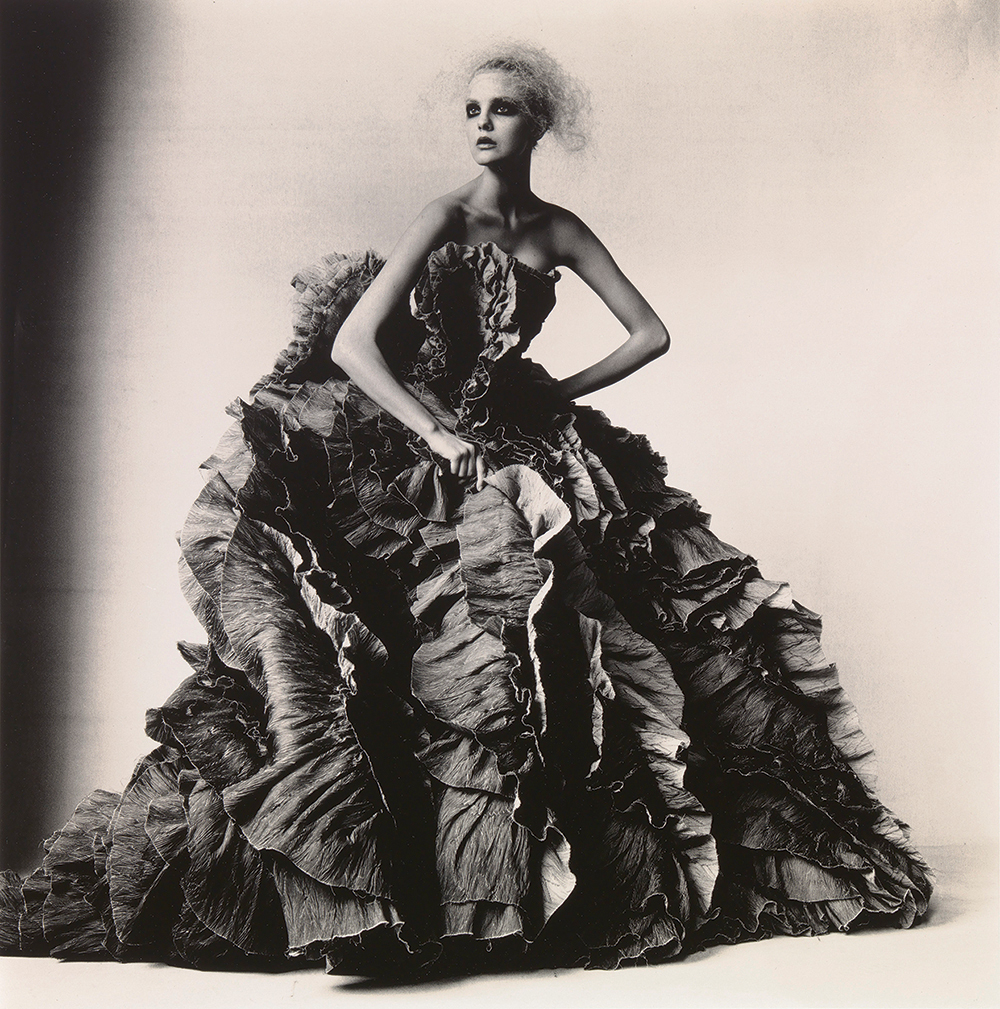

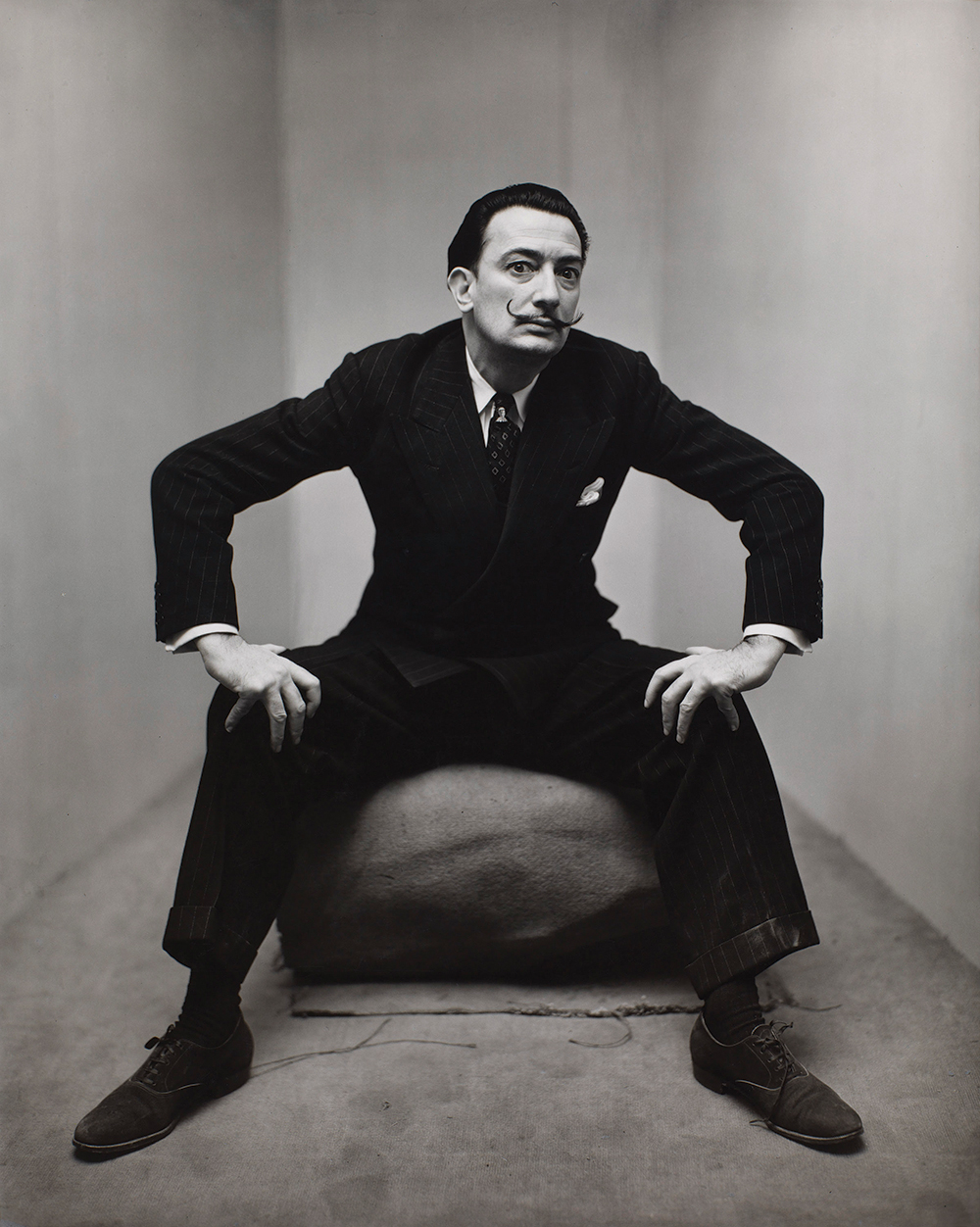

Perhaps more notable is that all 100 images donated to SAAM were printed during the artist’s lifetime and approved by Irving Penn personally, 60 of which Penn himself donated personally to the Smithsonian in 1988 and which span his career from 1944 to 1986. The photographs donated by Penn’s foundation, and now on display at The Dallas Museum of Art, include unpublished early works of postwar Europe; a host of color photographs produced for by Penn for his editorial and advertising work—some of his most highly recognizable fashion imagery, celebrity portraits which include Salvador Dali, Leontyne Price & Truman Capote, and a selection of still-lifes.

“Penn’s role as an innovator in the medium of photography is a compelling story, and the DMA is pleased to reveal, and celebrate, his artistic legacy,” Canterbury explains. Here Iris Covet Book spends time with Sue Canterbury to discuss the iconic photographers career & life’s work and the exhibition Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty.

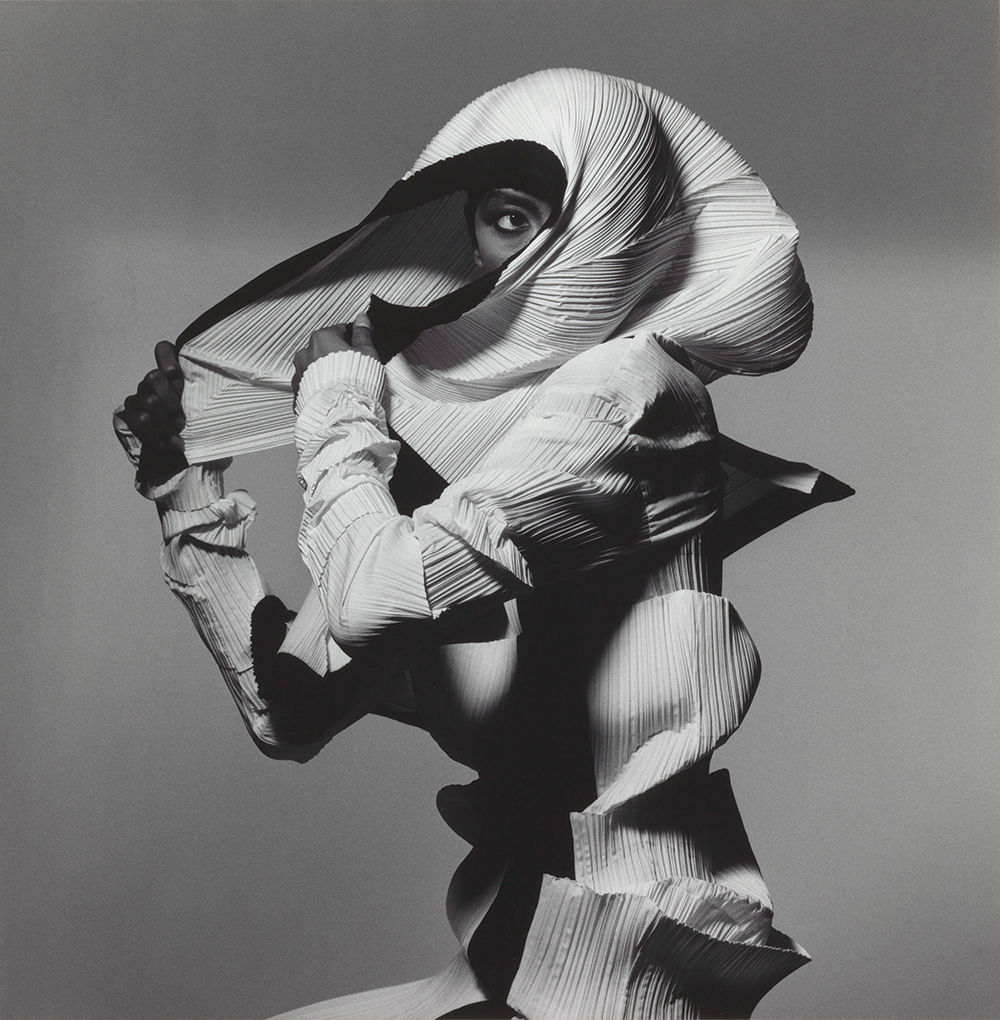

Head In Ice, New York, 2002 by Irving Penn

A lot of people are familiar with Irving Penn’s work as a fashion photographer and for the work that he did later on in life. What foremost qualities stands out to you about Irving Penn’s work and his creative process?

In some of his early works he had this real attraction towards surrealism. His earliest photographs of shop windows, or storefronts with cut-out signs have a surrealistic quality to them. This sort of approach continues throughout. Sometimes it’s not as obvious as others, but it’s there.

Another thing that stands out is his idea of beauty as an absolute value, and his interest in how people present themselves. All cultures have their way of self-adornment, which is part of what makes them beautiful. It’s how that culture sees and appreciates beauty.

He had, I think, a fascination with that beauty. While on assignment in San Francisco, you see it in the way he photographs the Hell’s Angels and the hippies. It didn’t really matter if you were a model from Manhattan or a woman from New Guinea. It’s just part of a continuum within his work.

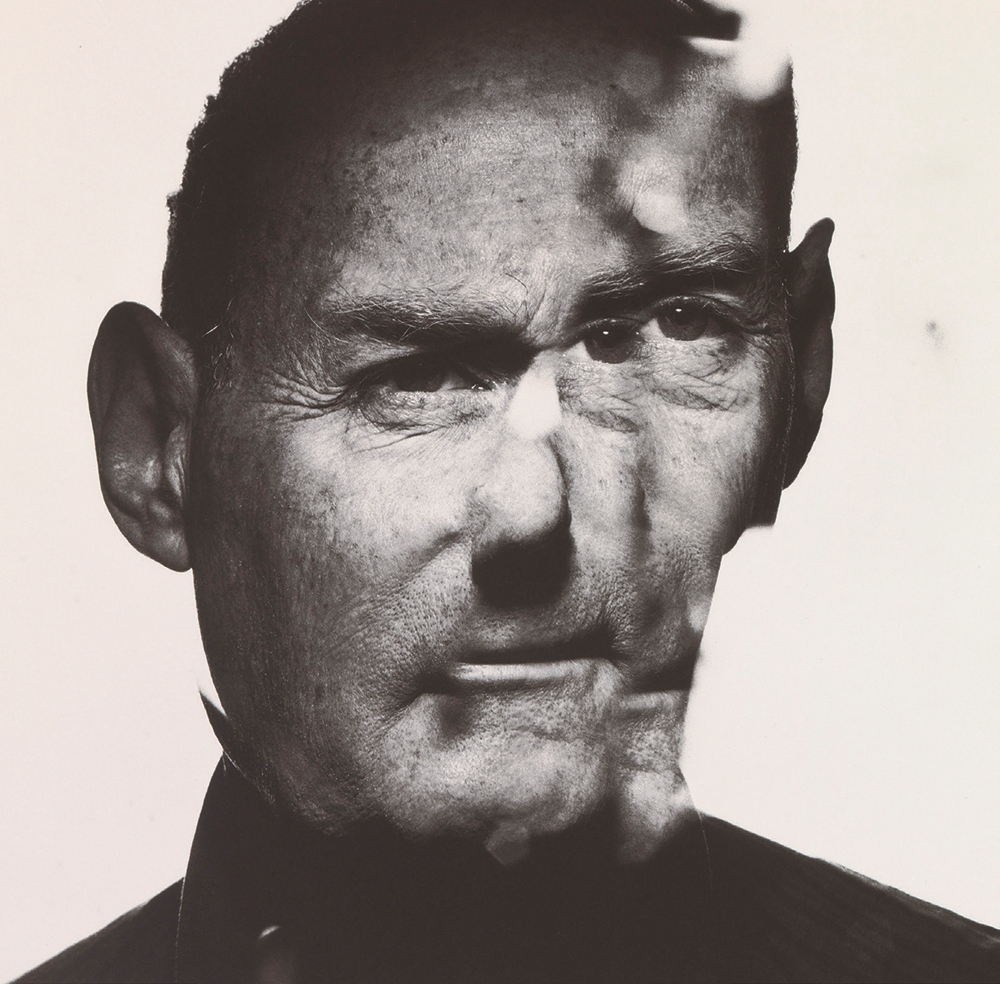

Truman Capote, New York, 1979 by Irving Penn

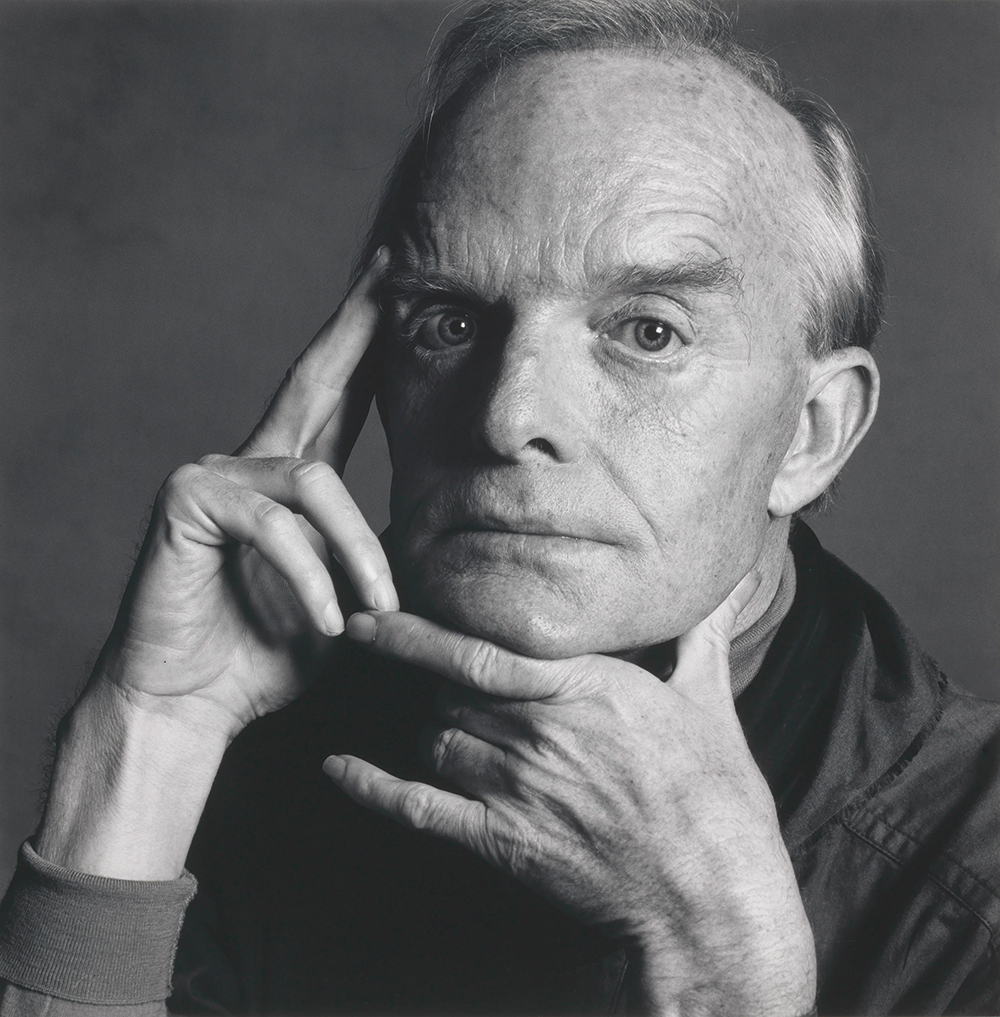

Issue Miyake Fashion: White and Black, New York, 1990 by Irving Penn

Do you think that his approach to beauty, and how he understood it, helped him to become an innovator in the world of photography?

I think one way he was really an innovator was his approach to fashion. In the ’40s, fashion photos shoots had become tableau-like. A model would wear a particular dress, and a contextual situation would be created around her to basically give her the excuse for her wearing the dress. It was a lot of work to put it all together, but another aspect of it, it really abstracted the eye from the main event, which was the piece of clothing.

In contrast, Penn deviated from that aesthetic and pushed a very stripped down background, which would have been considered minimal for the time. That’s something we also see with his portraiture, for example the Warner portraits, in how he stripped things down. The result is, there’s this wonderful emphasis on silhouette, light, and composition. And for his commercial clients, the designers and editors, this approach emphasized the costume itself. Because of its simplicity and elegance, other photographers began imitating.

Salvador Dali, New York, 1947 by Irving Penn

Were there any photographs in the exhibition that surprised you or that you were particularly drawn to?

I think in particular, the lead image which is on the cover of the catalog, Head in Ice. This image is unlike everything else that’s in the exhibition and it demonstrates his unusual approach to subject matter. After submerging a mannequin’s head in water and freezing it, Penn proceeded to photograph the head through the fractured block of ice and it’s incredibly surrealistic. He was always thinking outside of the box in his approach to his subject matter which is why he was such an exemplar in the advertising industry. He made images that were memorable.

Yeah, it almost appears as if it is a painting, the part where it’s fractured, as if it could almost be like texture from brush strokes on a painting. There’s a very painter-like quality about that image.

Yes, that’s very true. It’s sort of interesting you bringing that up, because when he was starting out, painting was what he wanted to do. So there are particular aspects of that in his work, and in the approach of it.

For a long time, photography wasn’t really respected as a viable art-form the way that painting was. Much of Penn’s work was geared towards commercial publications, but what about his work as an artist?

He had already began working in that vein to some degree in the ’40s. You see it in his early shots from Philadelphia or New York, and also the ones he did in Mexico in 1941, some of which he submitted to a surrealist magazine at that time. So he was already thinking of photography as an art form early on. It isn’t until 1942, when he returns from Mexico that he is hired by Vogue.

That’s when Penn became very oriented towards mass-publication magazines. A lot of photographers leading up to mid-century were picking up the greatest exposure through printed matter. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, when magazines quality began to suffer due to poor paper qualities and printing techniques, Penn turned away from that. It’s in the ’60s when he starts his research and began working with the platinum printing process. Still throughout the entire body of work, both commercial and art, his approach is always an unusual one.

With the accessibility and the popularity that has happened with photography, how do you think that society’s view of photography as art is going to continue to evolve over time?

It definitely becomes more democratized, not just because of digital, but because of smartphones actually. That has been one of the challenges for this exhibition because we realize we are speaking to a generation that may have never seen a piece of film negative.

They don’t understand the concept of shutter speeds or apertures. So we’ve been trying to do some other educational things on the side to inform them about what that process is because it’s difficult for them to realize what Penn accomplished and how he accomplished it.

Irving Penn In a Cracked Mirror, New York, 1986 by Irving Penn

Especially because the printing techniques and the technology was so different then. Today everything is Inkjet. Unless you’re still working with film creatively, and doing those types of printing processes.

Very true. His processes were so evolved. He had to be a bit of a scientist and alchemist in the dark room, not just an artist. I think another aspect of his work that people don’t realize is how he altered cameras to suit his needs.

An example of this is in the Underfoot series. Penn used a 35 millimeter that he had modified by attaching a tube to the body. At the end of the tube he put a macro-lens. So essentially, he could sit in a chair in the street and have the macro lens hovering as close as possible over the chewing gum. The detail, of course, is really quite amazing. He makes grains of grit and dirt sparkle like crystals. It has this wonderful tone and richness.

Another example of how he altered cameras, was in the ’70s. He purchased a Folmer & Schwing wide format, banquet-view camera, which had a 12 by 20 plate on it. That’s a camera that was manufactured in about 1910. So he reaches way back in technology, pulls it forward to ’79 and does these really great still-lifes. The wide format still-lifes in the show were shot with that banquet-view camera. What it meant was that he did not have to enlarge it. It was a direct contact print. So the resolution was really wonderful. Then he would go on to take that same camera in the ’90s and use it for his experiments with moving the light.

What are you hoping people will garner from the exhibition?

One of the things that I want them to take away, is that Penn’s work encompassed so much more than his body of fashion work. There was the public commercial areas where he had his own clients, but also his personal work that he did on the side, and how innovative he was with his eye – to understand how he saw beauty. Penn felt that he could pull beauty from any object, given the right circumstances, proven by his street trash, for instance.

One assistant recounted many years later how he would go out to find things for Penn to photograph. He would bring back things he thought were interesting. Penn said to him, “I don’t want things that are interesting. I want things that can be made interesting through photography.”

It’s a subtle difference, but it’s a big one. And that’s something that he brings to all of his work. That beauty extends far outside the fashion body of his work to encompass all of it, really. Everything is done with such intention, such precision, such perfection because he was a perfectionist. It’s incredible to see these really wonderful works and to realize what went into them.