BETTINA RHEIMS

Interview by Marc Sifuentes | Photography by Bettina Rheims

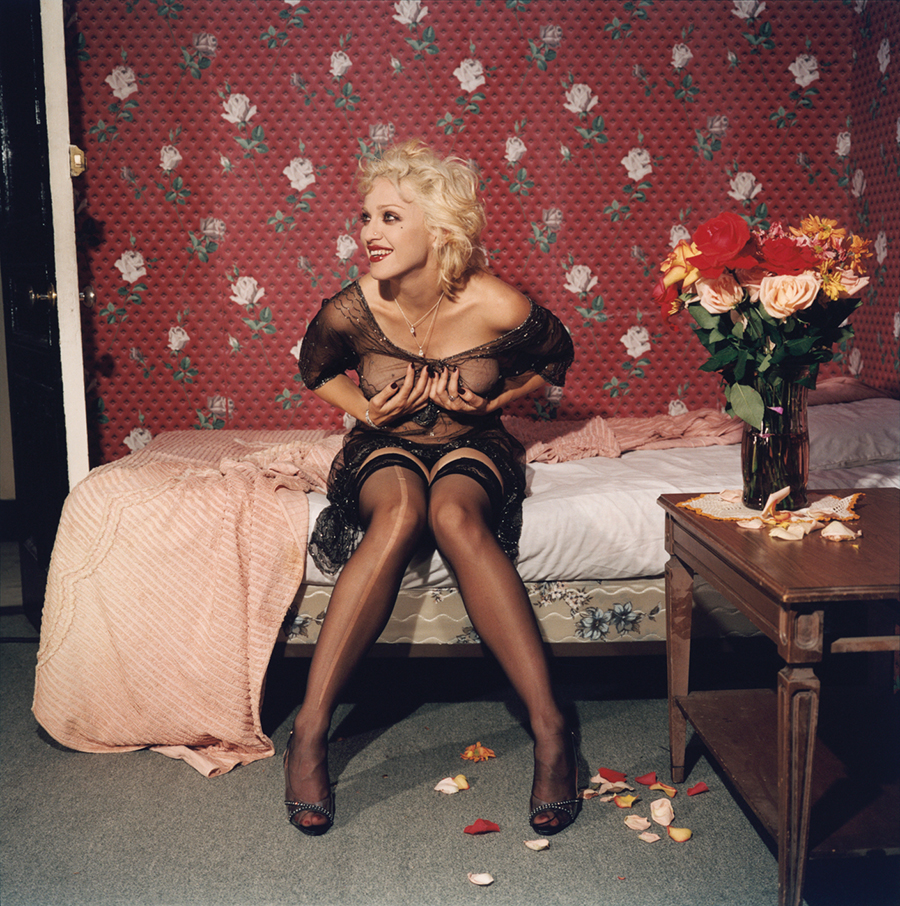

Madonna laughing and holding her breast, September 1994, New York © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen

Today in social media, whether through Instagram or Facebook, there is heated debate throughout the world surrounding gender constructs and sexuality. Thanks to Bettina Rheims and other female pioneers of the arts, women are able to express their own views of what it means to be female through images rather than just words. Beginning her career in France in 1978, Bettina photographed the female body, and her love of shooting flesh began. Soon that love turned into a career of portraying women as raw, sexual, real, and obstinately their own. Now, from Lena Dunham to Laverne Cox, powerful influencers are free to share their own views of what they think it means to be a woman. Her latest book published by Taschen, self-titled Bettina Rheims, is the largest retrospective she has undergone so far, and each turn of the page exemplifies Rheims’ fascination with gender constructs, fragility and strength, and her signature blend of eroticism, vulnerability, and womanly beauty. We were fortunate enough to talk to Bettina and learn about how she first began behind the camera, working in photography for the past four decades, and what is next for her in the world of gender studies, fame, and feminism.

I wanted to start from the beginning of your career and ask if there was a single event which inspired your decision to become a photographer?

I never had a career plan; I never thought beyond the next step. When Serge Bramly gave me a camera in the mid-seventies, and I looked through the viewer, I had the feeling that I was home. I had all sorts of stupid jobs and none of them were really interesting to me. I looked through the viewer of that camera and I thought, “Wow this is incredible! I am going to spend the rest of my time focusing on what I want to look at and editing out the rest”. I never thought it could be a profession. I was raised to believe that I had to have a boring profession, and maybe I could do something on the side for pleasure. The idea that I was going to spend the rest of my life wanting to run to work was something I never thought about.

How do you feel your friendship with Helmut Newton influenced your career, if at all?

He became sort of my mentor. I met him through Nicole Wisniak who was doing this amazing magazine called Egoiste, and Helmut was her star photographer. They published my series of pictures of strippers, and Helmut said he wanted to meet the woman behind them. I was very shy about meeting him. He was something big, and I was only twenty-five years old. He decided he was going to coach me somehow. So, every Thursday when Helmut and (his wife) June were in Paris, we would meet for dinner and I would bring my latest pictures. He would criticize them, too much sometimes, but it grew into a real friendship. Helmut encouraged me a lot, he was the first person who told me I should work in color because I was only shooting in black and white. He said if I was going to be a photographer, I had to start shooting in color and going out in real life.

When Helmut would give you a harsh critique, did you ever argue that you had your own style and beliefs that you wanted to stay true to or did you absorb his criticism and learn from it?

I wasn’t taking all of his advice because his vision of women was so different from mine. Our pictures were very different. He was into luxury and treating women like objects in his photography, and I have a different relationship with women. One day I figured enough was enough and I decided “to hell with him” and I slammed the door on our relationship. We did not talk for awhile, but soon he came back. It was like it always was, but he never asked to see my pictures again. He would come to all of my shows though.

Do you remember what Mr. Newton might have said that upset you at that time?

Yes, I think it was some stupid ad job, and he said this horrible thing. He came to my studio one Sunday and he asked to see my latest work. There was a big portfolio that he started going through, and at one point he said, “Do people really pay you to do that?”. I was so offended. I wasn’t going to take it anymore. That was it professionally, but we stayed friends.

You were talking about the relationship you have with women as your subject, what do you feel are some of the main differences between European and American ideas of feminine sexuality?

I think we Europeans are a much more open and straightforward, and there is a lot of hypocrisy in America these days about magazines and what people do and show. What is “politically correct” has become huge in the States and if I had started my career again thirty years later I wouldn’t have found a magazine in the States, maybe a little underground magazine, but no major one would publish my work. In Europe, it’s different. We have always talked in a much more open way about sexuality. It’s not even an issue, it’s just there, a part of our everyday life. Not that I find European magazines very exciting these days, but basically I think we have lost a lot of our freedom. I used to love looking at photography books and magazines, and today I would not know what to buy. Everything bores me and it is so predictable.

I feel like there is a lot of political correctness happening right now which has censored and changed the dialogue of the arts. On Instagram you cannot even show a woman’s nipple without being reprimanded with a warning from the company.

Well, that’s ridiculous! I mean, this is part of the general hypocrisy!

It is also specific to women. If men are shirtless you can post as many nipples as you want, but if a woman does then the photo gets deleted and she becomes a target for bullies and internet trolls.

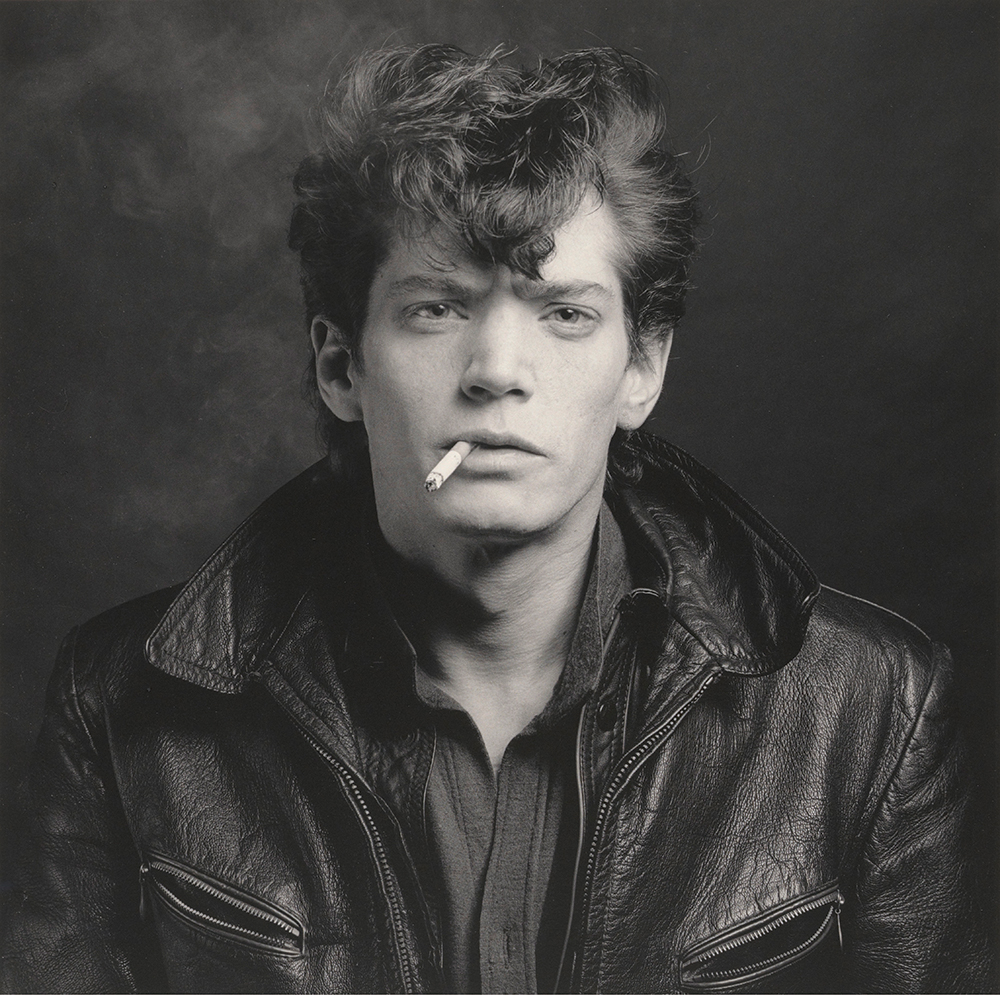

Well, beyond Instagram, do you think Robert Mapplethorpe could be doing today what he was doing decades ago throughout his whole career?

No, probably not. (laughs)

Probably not. We were pioneers! We were opening doors.

Rose Mc Gowan sinking in a bath of roses, September 1996, New York © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen

You have allowed us to publish some of our favorite images from your new retrospective book published by Taschen entitled Bettina Rheims, could you tell us how you came up for the concept of Rose McGowan in a bathtub full of roses?

Well, I was working very closely with a magazine called Details, and at the time it was a very brilliant magazine. James Truman was the editor-in-chief, and they had a brilliant stylist, Bill Mullen, and we worked very closely together. I worked with them for probably four or five years, five or six times a year. They were inventing stories and I went to the states and shot them. I cannot remember exactly, but I do remember that everything came from our conversations with Bill. We were very free with the pictures and what we wanted to do, and the celebrities were also very free and very brave with the images. They were going ahead and giving their best, and it was really a very creative time for me. Bill and I had an ongoing conversation and I said let’s put her in the bathtub, and the roses would eventually appear and we started pulling them apart. I never really have a concept of what I am going to shoot. I know who I am going to shoot, where I am going, and basically what kind of styling I am going for. I make this stupid list of props which always includes flowers and maybe food, and depending on where we go it just builds up. Working with me is more like a performance.

Many celebrities and their publicists seem to be much less open to risk taking than in the past, do you receive restrictions from talent that might limit your creative vision?

If people did not think my images suited them then they wouldn’t work with me. Some big celebrities have declined to work with me because they say that it is not a good fit for them, and I totally respect that! We all have the freedom to say yes or no. When I have a feeling that someone would not fit into my world, would not want to play these games with me, would not want to collaborate, would not want to trust me, then I just say no. It’s like a blind date. You have to make people fall in love with you and the other way around, and it has to be a feeling that you will be together for the rest of your life, and after a few hours you just leave them and never see them again! I love that. (laughs)

Kind of like a one night stand. (laughs)

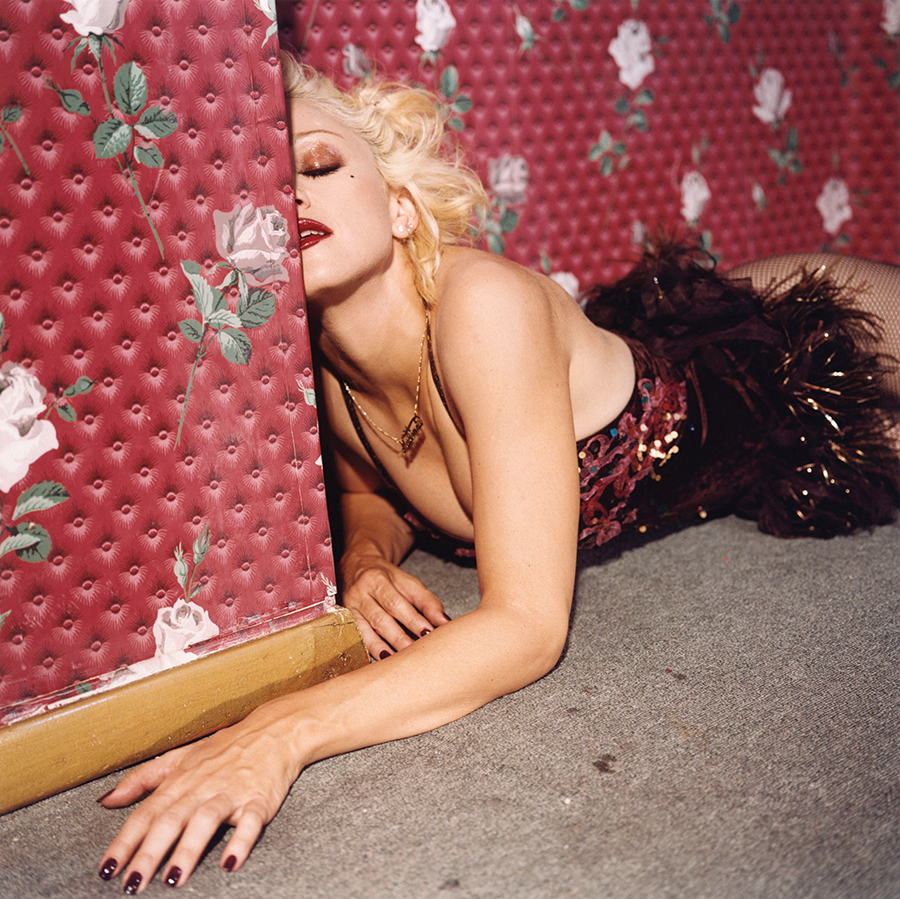

Madonna lying on the floor of a red room, September 1994, New York © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen

Madonna lying on the floor of a red room, September 1994, New York © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen

Well that brings us to this photo of Madonna, and considering everything you have said, we also know that Madonna is known to be very controlling, and she has a vision that she very rarely strays from. How did you find working with her on the creative level?

The fascinating thing is that she saw this book, my most famous book, Chambre Close, which features women taking off their clothes, anonymous women that I found in the street who took off their clothes in this cheap hotel in Paris, the ones you find near a railway. Madonna said, “Find this woman I want to work with her”, and it was easy because she was already into it.

She would not come to Paris and there were no hotel rooms like the ones in Chambre Close in New York City, so we had to fly over with these huge rolls of wallpaper and props to create the Parisian hotel room. It was just brilliant! One of the longest shoots ever, many hours, a whole night. I was exhausted. We had enough pictures to do a book, so I said let’s call it a day and go to sleep. But she just wanted to keep shooting more! She approved loads of photos, and she just loved them all. It was fantastic. I have barely used any of them really, out of the ones that she approved. Sometimes you meet someone and it’s amazing chemistry.

Breakfast with Monica Bellucci, November 1995, Paris © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen

Another photo we love is of Monica Bellucci with a plate full of pasta, can you tell us the story behind this photograph?

Well, that is a very old picture. I was working a lot with Monica when she was a model, and at that time girls started being very skinny and models started to become very androgynous. Monica was always really a feminine woman. We were in a tiny apartment shooting for The Face, a British magazine, and the stylist pulled out this latex type of red dress and I thought something was missing in the picture. I thought about Monica looking like one of these Italian actresses, like Sophia Loren, and in those films you would always see the female character cooking or eating in the kitchen.

So I thought let’s push it to the edge and give her pasta, and the pasta needed to be red because of the dress, and then it built up and suddenly this picture had become iconic, and I really do not know why or why any of these pictures became so famous. Some of these have been with me and surrounding me for more than twenty years but people still want to publish them and collector’s still want to buy the prints. I still haven’t really figured out what gives an image this iconic quality.

I think it has to do a lot with what you were saying earlier. When you have a good creative team and everyone connects, there’s this magic that happens–

It’s a magic moment and you know it doesn’t happen every time. After all these years you can always make a picture that can be published, but to make a great image, it’s a miracle. I know when the image is there. I stop shooting because there is like a red light that turns on in my head and I know that it cannot get better.

Kristin Scott Thomas playing with a blond wig, May 2002, Paris © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen

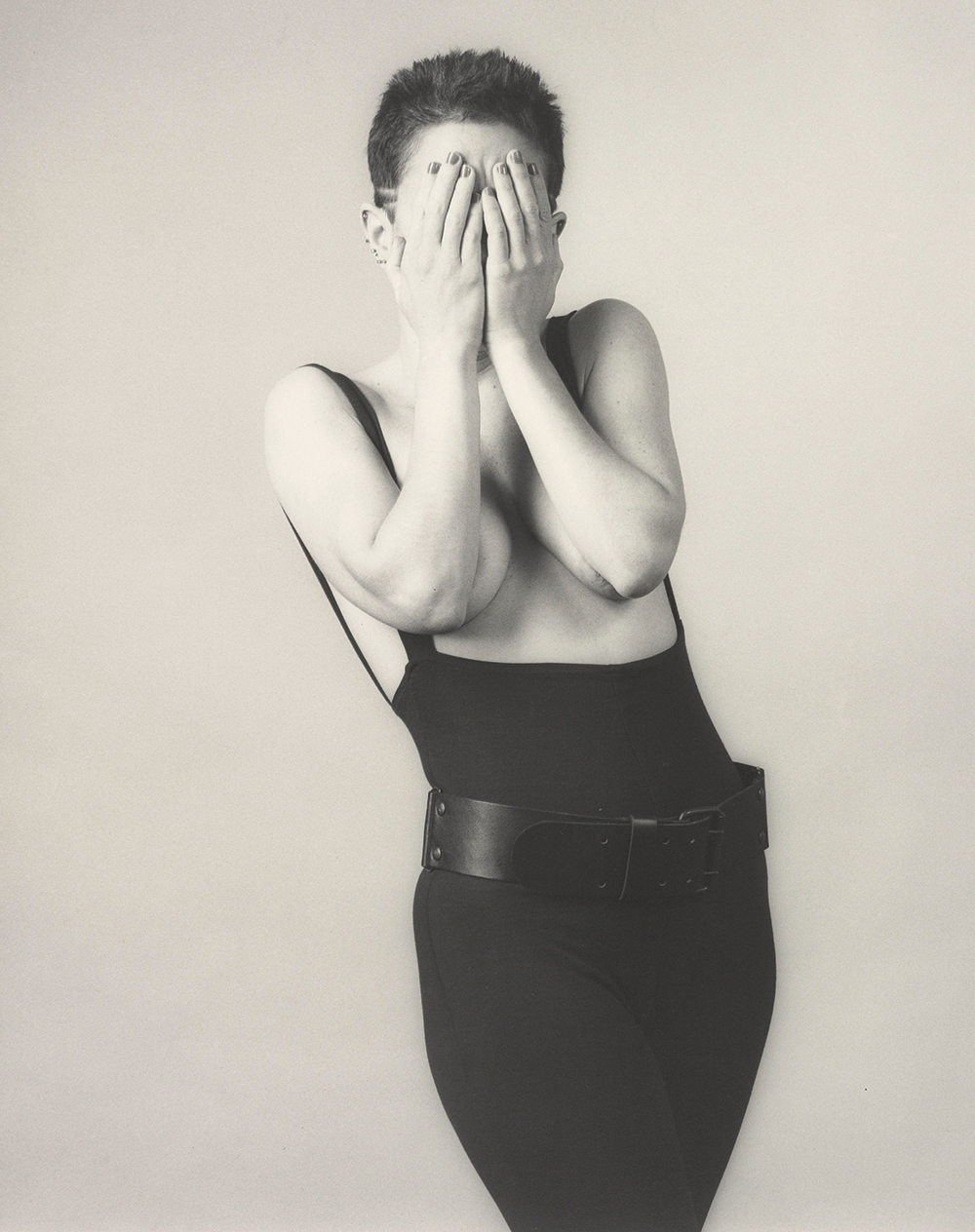

Our next photo is of a brunette Kristin Scott Thomas pulling off a blonde wig; can you tell us more about that image?

I remember my favorite hairdresser David Mallett was doing the hair, he was working with me constantly at that time and I remember calling him the night before and telling him to bring a blonde wig. I didn’t know what I would even do with it, or if she would even wear it, but then we went with it and it was perfect– but something was still missing. It was too normal, too pretty. Then as you would strip someone, I started stripping the wig off, and then it just happened. Intuition. The perfect moment. It’s what I love about photography.

From your vast library of archival photography, how long did it take you to edit down the photos to the final 500 images that are in this latest retrospective book?

A year of working on editing and doing the layouts and I wanted to have this little diary that would describe the life of a photographer. What my life has been like and the people who have helped me, taught me, collaborated with me, and inspired me. While also giving a tribute to all of the people who aren’t really talked about like the teams of assistants and hair and makeup, without these people none of these images would exist. I am not a writer who is alone with a white page and a pencil. It was probably two years total from meeting with Taschen to finishing everything.

As a woman working in photography for decades, did you find it hard starting out in a predominantly male-dominated industry years ago?

No. No, when I started in the late 70’s there were very few women in photography. A lot of women would say you betray us, but this was a long time ago. Feminists were angry with me because they thought these sexualized pictures should be taken by a man and not a woman, but eventually they understood and they backed me up. Obviously, those (images) could only be shot by a woman. This complicity, this close relationship, this trust that women have with me, they would not have it with a man. Not the same way. It could be more of a seductive relationship, but with me it’s a game and they know it is not a dangerous game. What’s the worst that could happen? They could regret they did a picture and call me back, but it doesn’t happen.

Earlier we discussed working with celebrities in the past, but what about today’s celebrity? Who would you be inspired by today in this new age of social media?

I would love to photograph Kim Kardashian. I think she is fascinating. I would love to go back to LA all of these years later and do another LA story. All of these girls, I am fascinated by these “It Girls” who have really done nothing but be there. They don’t do such great movies, they don’t have such a great voice, but they’re just there. For somebody of my generation, it’s absolutely fascinating.

I saw yesterday that Kim Kardashian is on the cover of Forbes Magazine because of what she has done with social media and how she has been able to brand herself and make millions simply by posting on Instagram and Snapchat. She is a social media mogul now. She captioned her own post of the photo #notbadforagirlwithnotalent.

I mean, I love the idea of no talent turned into genius! I have always been interested in what’s happening in the present, I’ve always been inspired by people I had found on the street, etc. You know, I wouldn’t post pictures of me or my grandson or even pictures of what I have on my plate, but you have to be fascinated by that. I would love to go back and do a new LA story with Bill Mullen, it would be great.

I wanted to also ask you about all of the books that you have published, and if you had to choose, which one is closest to your heart?

Oh my god that’s like asking which one of my family member’s would I not drown! Of course my heart goes to this current one because I worked so hard on it. I did it because I am a grandmother. Benedict Taschen was asking me for a long time if I wanted to do a big Bettina book and I always said it was too early, but then I became a grandmother which became something major in my life. I never thought I would, I thought I’d be dead! So, if I disappeared tomorrow I want to leave him something that he would know his grandmother by. I want him to read the text and see the images and go, “Wow, she really was different”. I love all of the books I did with my gender questions and I love my celebrity books and I love Chambre Close. My big pride is that maybe, just maybe, I have opened up some doors for people. I have helped people understand things that were not out in the public. I think that’s what we should do as artists, open doors. If they want to try to understand something or learn something, that’s how I start to work on a series. Because if I do not understand something. It always starts with a question, and I try to answer with my camera.

Was that your approach with diving into Gender Studies?

It really started with androgyny in the late 80’s. It was during the AIDS epidemic and all of our friends who were dying. I lost many of my friends in the late 80’s and early 90’s. I was doing a casting for a job, and at that casting was this man named Cameron who had long hair and who was very, very beautiful, but not feminine, more like a Christ figure. This girl came in named Josie who looked like a little boy, but had a woman’s body. I did a polaroid with the two of them, and I started wondering what is this androgynous thing and what is happening? This hasn’t been around since the 20’s. Then I went to London and started casting and I found this bunch of kids who weren’t able to have sex anymore because of AIDS,

so their only approach was seduction. They found this new androgyny, playing on both sides. After meeting Kim Harlow, I did a book, Kim, where she was transitioning and it was my first approach with transgenderism. Then she introduced me to her friends in the early 80’s, and people had no desire to look at transgender people. They thought they were just drag queens and they should just stay in the woods. Slowly, little by little, this phenomenon started to grow and take up space. I did a casting on Facebook and

said if you feel different and feel you belong somewhere else then send us a picture. I got hundreds of pictures from the suburbs of Rio to Orange County, from everywhere. Crying for help, saying “take me, I want to pose for you.” Then they came and it was brilliant! I met all of these people who decided they were a part of the third sex. It is fascinating, this new phenomenon.

Did you feel like you were helping them, the people who you met throughout those castings, by immortalizing their stories through photography?

There has always been that thing. I was going to bring them out of their bedrooms, from their closet, and they were proud of that. We talked and made this beautiful soundbyte where they discussed their difficulties and issues with family and friends and sex. It was brilliant. I have this feeling that when you support a cause like that you add stones to a monument that is being built, and it’s great! Voila!

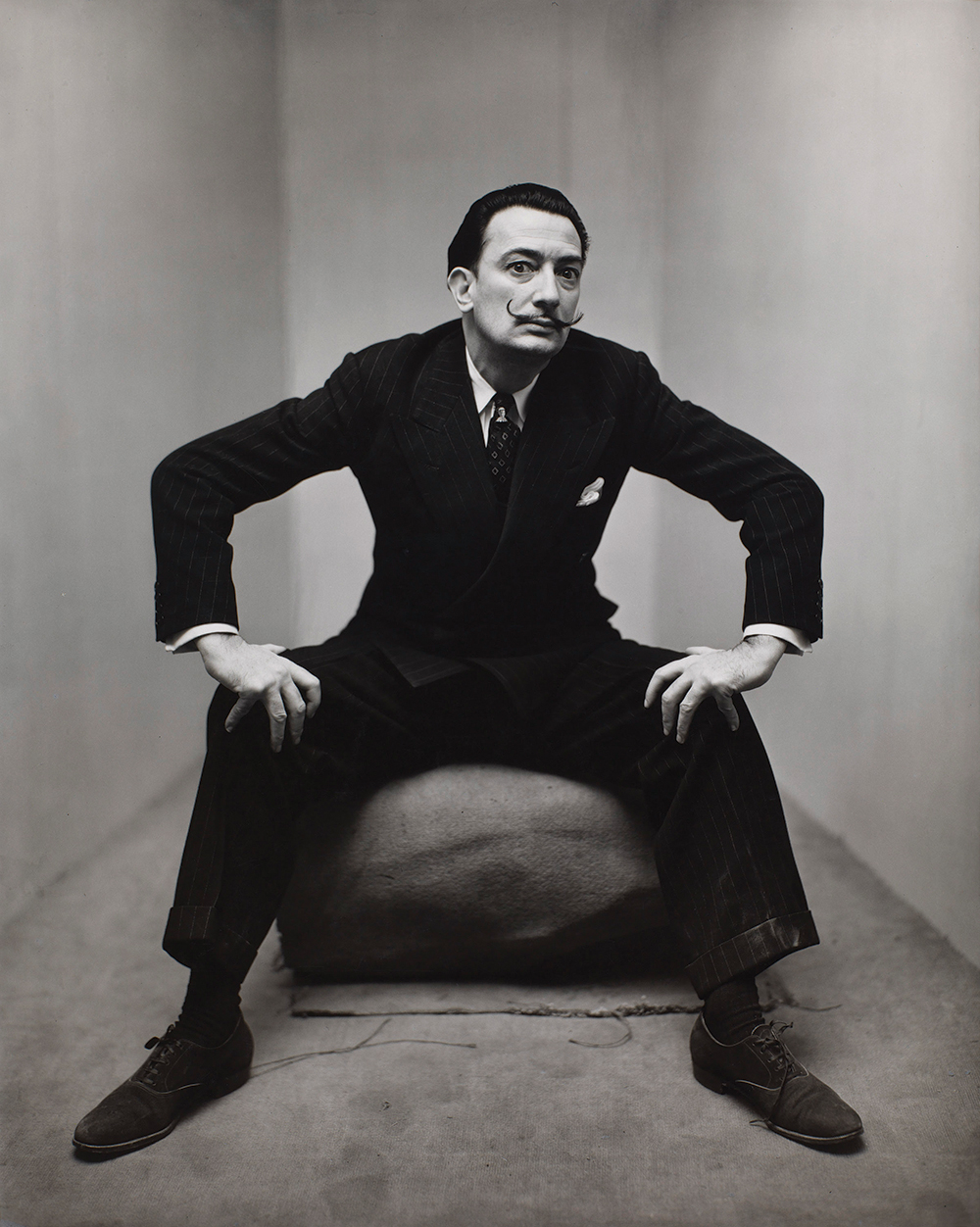

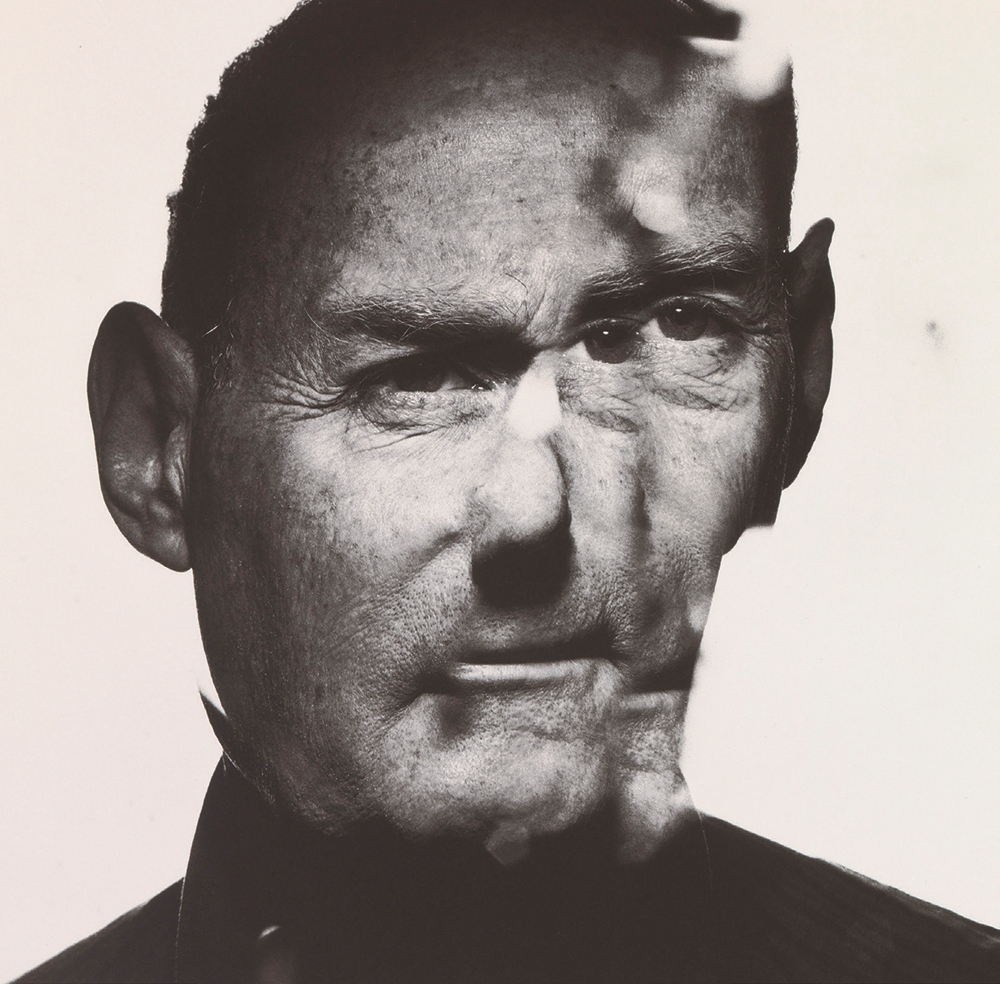

Actually, in our last issue we did an interview with the curator of the Irving Penn exhibit, and she mentioned that a lot of people were attending without any knowledge of film photography. She had to come up with an interactive way for them to realize that the images had an art to them because of the lighting and the the developing and the dark room. Many people today do not understand that the technical side of photography is also part of the art process. How do you give photography advice to the younger generation?

I wouldn’t know what to say. I don’t think photographing your food and your clothes is the way to get there. I mean, I think you have to have a vision and subject. You have to bring something new. The world is full of images. We’re overwhelmed! We’re drowning in images.

Today, if I were young, I definitely would not have become a photographer. Also, nobody realizes how much work it is, You know, to have a show at twenty five years old and be brilliant for five minutes is not that difficult. When you last for almost forty years and you are still working hard and getting up with headaches and toothaches and still getting to work, then you realize that this is all just work. Maybe you do not have to study, but it takes the experience of life. I don’t believe you can become a great photographer in twenty years, I think you have to live your life and then try to start thinking.

You spoke about how the book was for your grandchild, but what would you want your legacy to be as a photographer in general?

I don’t know, I never think about that. I think, “I am going on vacation now, but what I am going to be doing when I get back? Do I have a project? Do I have an idea?” Legacy would be very presumptuous. What’s the future of the world? What do we leave for our children? What great values, what essential thing? This is more important to me than what do I leave them.

I believe that we live in a very complicated time and there are so many issues that are more important than my own legacy. I just hope that we can conserve our freedom, that the environment isn’t going to eat us up– there are so many big issues at the beginning of this millennium. I have always lived an honest life and my work was always honest, it has always come from my heart. There was never a calculation to see what I had to do to work in fashion or what I had to do to work with certain people. I just kept on doing what I thought was right.

Karen Elson, nue couronnée de fleurs, Octobre 2000, Paris © Bettina Rheims | Courtesy of Taschen