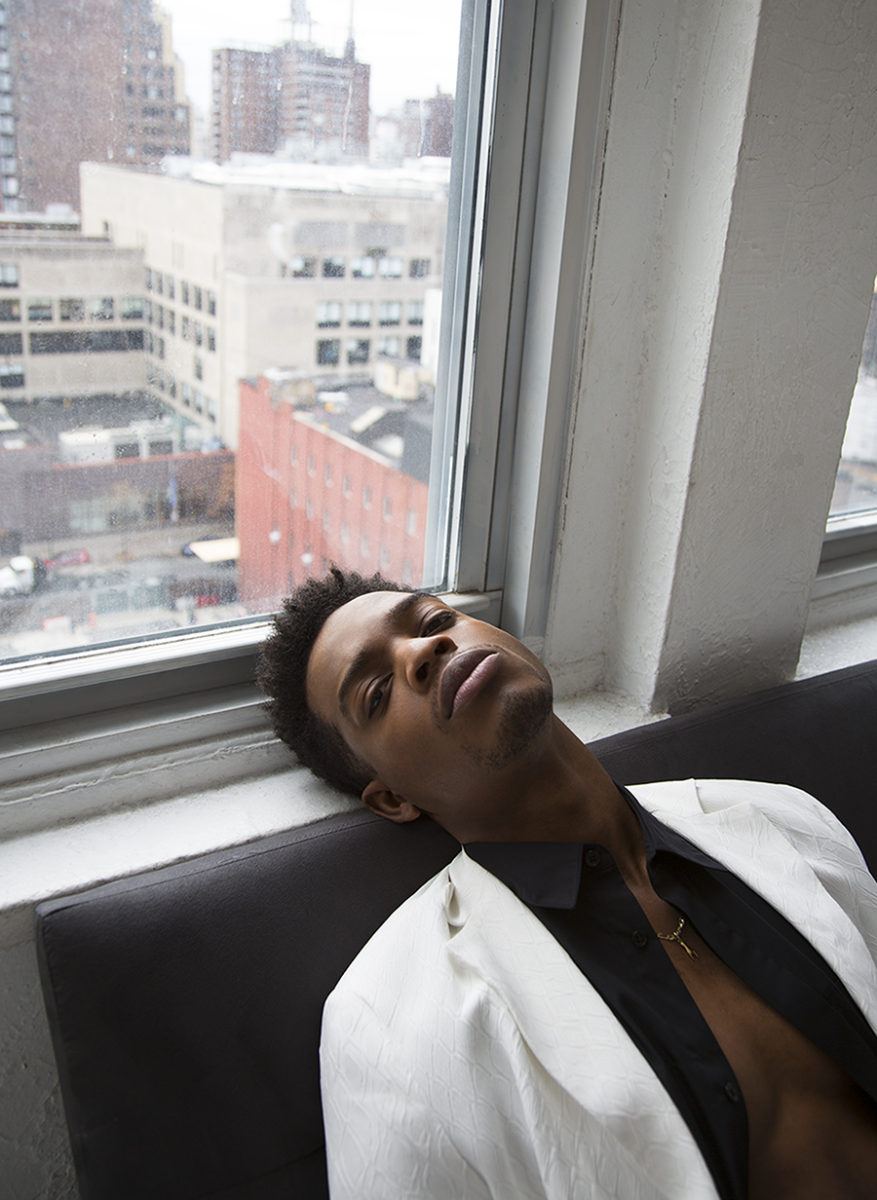

STEPHAN JAMES

Full Look by Z Zegna

With a Golden Globe nomination for Homecoming under his belt and rounds of praise for his work in If Beale Street Could Talk, actor Stephan James is a storytelling force to be reckoned with.

Photographer: Karl Simone | Fashion Editor & Stylist: Marc Sifuentes | Interviewer: Stacy-Ann Ellis | Creative Director: Louis Liu | Groomer: Tara Lauren for Epiphany Artist Group using Kiehl’s | Features Editor & Producer: Ben Price | Photo Assistant: Ned Witrogen

Full Look by Z Zegna

Stephan James is well aware of the power of his eyes. For the better part of If Beale Street Could Talk’s two-hour run time, his gaze as Alfonso “Fonny” Hunt from James Baldwin’s 1974 novel of the same name, is plastered across the full length of the cinema screen. As his deep, pleading eyes focus maddeningly on his fiancée, Tish Rivers (played by KiKi Layne), or well up from behind prison walls, they wring out raw emotions from the audience scene by scene.

We’ve seen these penetrating eyes before in films like Selma and Race, and in the FOX TV series, Shots Fired. “Some actors, they use their eyes to carry a lot of emotion, I think that’s part of what I do,” James says over an early morning phone call, humbly attributing his affecting stare to the skills he’s honed as an actor. “It’s the subtleties sometimes.”

James’ grasp on director Barry Jenkins’ vision and intention for the Baldwin adaptation is clear, as is the importance of his role in delivering it. The first time the Toronto, Canada native read the novel, or any Baldwin literature for that matter, was after he’d read and fallen in love with Jenkins’ screenplay. However, the gravity of Baldwin’s words (and the necessity to be a proper vessel for them) were not lost on him.

“I was really blown away by the language of Baldwin,” he says, even describing his verbiage as Shakespearean. “Just how descriptive and vivid he was, the way he described love, the way he described tragedy in the same breath. The poetry in which he went about doing it. And then again those themes, the fact that this man wrote this book in 1974 and it just felt so relevant.”

Jenkins’ Beale Street follows the newly engaged black Harlem couple as they navigate major life hurdles occurring at the same time. (Shortly after Fonny is falsely ID’d and imprisoned for the rape of a Puerto Rican woman, Tish finds out she is pregnant with his son.) As the story weaves in and out of the befores, durings and afters of Fonny’s grim predicament, Jenkins explores topics such as community, vulnerability, restraint and sacrifice. However, one particular theme is paramount: bonafide black love. “This film is showing what the power of black love is able to help us get through,” he says.

IRIS Covet Book caught up with Stephan James to dig into his future as a leading man, the threads that bind him with his character, Fonny, and the way If Beale Street Could Talk challenged society’s narrow expectations of black men.

Full Look by Z Zegna

Full Look by The Saltings NYC, Shoes by Bally

Once If Beale Street Could Talk wrapped, what was your experience watching the finished film for the first time?

The first thing that struck me about the film was it felt very much like a Barry Jenkins film. It felt like a movie about faces more so than places, and I think that it’s pretty striking when you have these characters talking directly to camera, cutting out the middleman. And Barry Jenkins, by the way, would never tell us when he’s doing those shots. He would never plan them. He would feel it out as a scene was going along and say, “Okay, well now I’m going to put it directly in your face, so let’s go.” It’s a great tool to cut out the space between the audience and the characters and just have a direct line of conversation.

When pursuing the role, what part of yourself did you see in Fonny reading from the page?

First and foremost, Fonny is an artist. He’s an artist much like I’m an artist. Outside of acting I also like to paint, and Fonny is a sculptor. He’s deeply, deeply sentimental and artistic and he loves a lot, so I found some similarities with just his artistry. And then maybe a couple of months before hearing about this film, I had become infatuated with the Kalief Browder story. It was striking because as soon as I read this screenplay, I thought of Kalief immediately. I thought that their stories were so similar, almost unfortunately similar. The fact that Baldwin wrote these words in 1974 and they had so much resonance in 2017 when I was reading this script and when I was reading this novel. It was just something inside of me that told me, wow, Fonny is Kalief’s story. Fonny is an opportunity to give a voice to young men like Kalief and so many other young men across the country who are going through the same sort of ordeal. So I feel like I kind of made the connection really quickly. And ultimately it just felt important. It felt important to embody somebody like Fonny. Although he is a fictional character, and all these characters are fictional characters, they’re representative of very real people.

It was refreshing to see a black man being just an artist—not sketchy, not a hustler—on screen. What does that communicate about the scope of the black man?

This film challenges a lot of ideologies in terms of what it means to be a black man, what black love means and the idea of what black families mean. Seeing Fonny as this deeply sentimental artist—he’s a sculptor, he takes something that is seemingly nothing and it’s a labor of love for him—I think that it’s important for the psyche of black men, young black men, watching this film. Often, especially in state of mind and art in general, I feel like there’s a very limited perspective when it comes to the portrayal of black men and what black masculinity looks like. Especially when it comes to these men who have been criminalized. We never get to see them as artists, sculptors, lovers, fathers, husbands. I think that this film is revolutionary in that way.

You look at some of the scenes—particularly the scene between Daniel and Fonny. To have these two young black men who have been criminalized be able to sit down at the table and open up to one another, be completely vulnerable with each other and share their deepest darkest secrets with each other, their fears, the things that keep them up [at night]. What a special thing that is, just for the psychology of these young men watching this film. The fact that they get to see that we can be like this, we can lean on our brothers like this… If it’s only one person, then we can use our brothers in this way and love in this way. I just think it’s a powerful, powerful message that’s being said.

Did you find yourself at any point angry just thinking about the helplessness conveyed in Fonny’s story?

Yeah… I mean the thing is this. Baldwin says, “to be a black person in America is to be in a constant state of rage,” but on a bigger scale, I think that the biggest theme in this book and in this movie in general is love. And in particular, it’s black love. It’s this idea that for hundreds of years the black community in general has been born into a world where the chips are stacked against them. Where we have an unjust system, a system that’s supposed to be a place to protect us but is seemingly failing to protect a group of people time and time and time again. I think that this film is showing what the power of black love is able to help us get through.

I think that despite these tumultuous circumstances thet Tish and Fonny find themselves in, the darkest times, it’s this love. It’s this unbroken, undying love in the face of adversity that has kept them going. That’s the only reason why at the end of the film, despite the circumstances, Fonny is still in prison, but it’s this love that’s helping to raise their child, this five-year-old boy now. That’s the only thing that’s kept them going. That’s the bigger message. So of course you get angry, and it’d be impossible not to get angry. It’s sort of the world that we live in, but I think Baldwin’s making a statement on the power of black love.

Full Look by Roberto Cavalli

Jacket and Shirt by Helmut Lang, Pants by Burberry

The nuance of that love really presents itself at the grocery store. After Fonny defended Tish from a creep in the store, Tish had to protect Fonny from a racist police officer who threatened to arrest him and called him “boy” in the same breath. Tish didn’t think twice when she spoke up to Officer Bell and said, “He is not a boy.” There’s so much energy packed into the scene where Fonny defends Tish, then she turns around and defends his manhood from a racist police officer. There’s tension between you and the officer, the restraint you have to exercise, and Tish’s fearlessness overcoming her physical fear.

I definitely saw that. I saw the restraint that many young men have to learn at a very young age and black men have to learn at a very young age, in terms of how to deal with police. It’s something we’re sort of instructed to [do] as young men. There’s definitely a lot of energy between Tish and Officer Bell, the idea that a black woman can be strong and stand behind her partner in this way. I saw a level of frustration, too, maybe between Tish and Fonny. Almost like, I don’t need you to protect me, and I should be the one protecting you. It’s ironic that I was protecting you and now you have to protect me. It’s interesting how the shift in the scene happens so quickly.

It seems to also speak to the power of the black woman in general. In the film, we see Tish, her mother, Sharon, and her sister, Ernestine—even Fonny’s mother, Mrs. Hunt, has a powerful (albeit negative) presence. Do you feel like there’s something to intentionally be said about women with this film?

In general, our ideologies have been challenged in this film. What it means to be a strong black woman. The fact that it wasn’t Frank who went to Puerto Rico to find Fonny’s accuser, it was Sharon. She hopped up on the plane and she went to find the accuser to see if she could plead for Fonny’s innocence and for his freedom. I think there’s something to be said for the family dynamic and how there’s a balance of power. Especially if you look at Tish’s family, how sometimes it’s Frank that’s out working and trying to make sure that everything’s good before the baby comes out. Sharon’s version of working is, I’m gonna hop on a plane and go to Puerto Rico. It’s just the balance of sharing those duties of the responsibilities. It’s Tish showing the strength of a black woman. She’s working all the way up until the last minute that this baby’s supposed to come into the world. There’s a lot of commentary in terms of what it means to be a strong black woman. This whole novel, this whole story, is told from the perspective of a strong black woman. It’s told from Tish’s eyes, and I think that Tish really grows into herself in this film. You see her grow up pretty quickly and step into that womanly, motherly type of role.

Jacket by Alexander McQueen, Shirt by Roberto Cavalli

Jacket by Alexander McQueen, Shirt by Roberto Cavalli

Jacket by Alexander McQueen, Shirt by Roberto Cavalli

Do you think that you would be able to maintain that sense of togetherness—in terms of love, sanity, optimism—if you were in Fonny’s legal situation? Especially if there was not a guarantee of freedom in sight.

I really couldn’t say, man, I really couldn’t say. I’ve never been to prison. I have no clue what that’s like. Those walls are meant to break people—physically, mentally, spiritually, all the above. So I can’t say. I really, really, can’t say. I’m thankful I’ve seen examples now in cinema of Fonny who was able to sustain himself through all this, but I’ve also seen examples of Kalief Browder who even after two years after his release from prison committed suicide. So there’s no telling what a thing like that puts you through.

That plays out with Fonny and Daniel’s conversation. Fonny tried to console him about his post-prison emotions and his acclimation to the world, and Daniel stressed that he just didn’t understand.

Absolutely, and like I said, these walls are meant to break these men, so after they come out, they’re still dealing with all of this trauma. This PTSD, if you will. So the conversation is not only about why they’re in there—obviously wrongfully, of course—but what to do to them and with them after they come out? How do we treat them? Especially when we know that we’ve wronged them. The system has wronged them. Is there a system in place now to help them get their lives back together and to regain humanity? What do we do with these young men who have been wrongfully imprisoned and are now having to deal with the trauma and the acclimation back into civilian life in general?

After both this performance and your role in Homecoming, the world is paying attention. How does it feel to see that growth and recognition?

We don’t make art from a place where we want a bunch of awards and stuff like that. I appreciate the recognition, that the people are seeing the work, and ultimately if that sort of recognition means that more people will see the work, you know, because it’s being regarded and respected as such, then that’s what I want. If [Golden Globe] nominations mean more people get to see Beale Street and more people get to see Homecoming, then I’m all for it.

Were there any key professional takeaways from working with Barry Jenkins for Beale Street and Julia Roberts for Homecoming?

There’s just so much. I’m so grateful for Barry Jenkins, who’s probably one of the great humanists that we have in this business. One of the incredible storytellers who’s always pushing the envelope, I believe, in cinema. I’m grateful to be able to tell stories with a man like that. Probably one of the most patient directors I’ve ever worked with who just allows moments to breathe and live. And then Homecoming, obviously I’m in a position where I’m sitting across from one of the biggest actresses in the history of acting. I’m able to pick up gems from her on a daily basis about etiquette, how you go about your work day, and how you do your homework. I wouldn’t say it’s one particular thing, but getting to spend months with these people with my favorite filmmakers and to be able to pick up the nuances in their work, it’s really an invaluable experience, altogether.

You’ve tackled stories of black love, injustice, tragedy, etc. Are there any stories or characters you’d like to explore next?

I don’t know, I wanna be in a comedy. I wanna be James Bond, I wanna do a Mission Impossible. I wanna be Batman. I don’t see any limits in terms of what I wanna do. I just see a whole world of… I mean I really feel like I’m scratching the surface, honestly. I want to do everything.

Jacket and Shirt by Bally

Jacket and Shirt by Bally