DAVID WILLS DISCUSSES HIS NEW BOOK – NAT KING COLE ‘STARDUST’

The definitive photo book on Nat King Cole—in honor of his extraordinary legacy as a singer, jazz musician, style icon, and civil rights advocate.

Foreword by Nat King Cole’s daughters:

Introduction by Johnny Mathis

Additional contributors: Quincy Jones and Leslie Uggams.

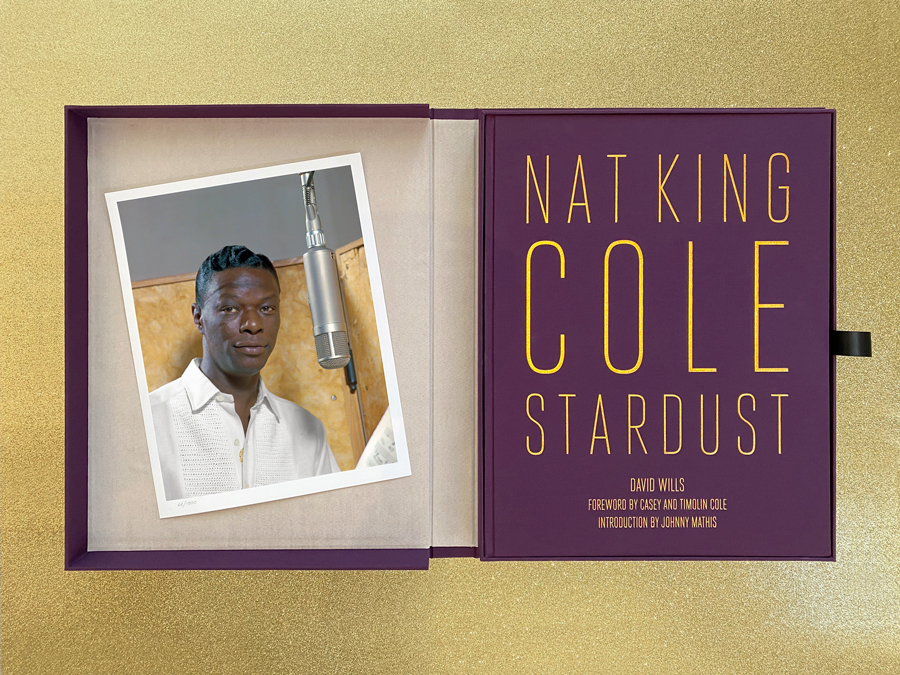

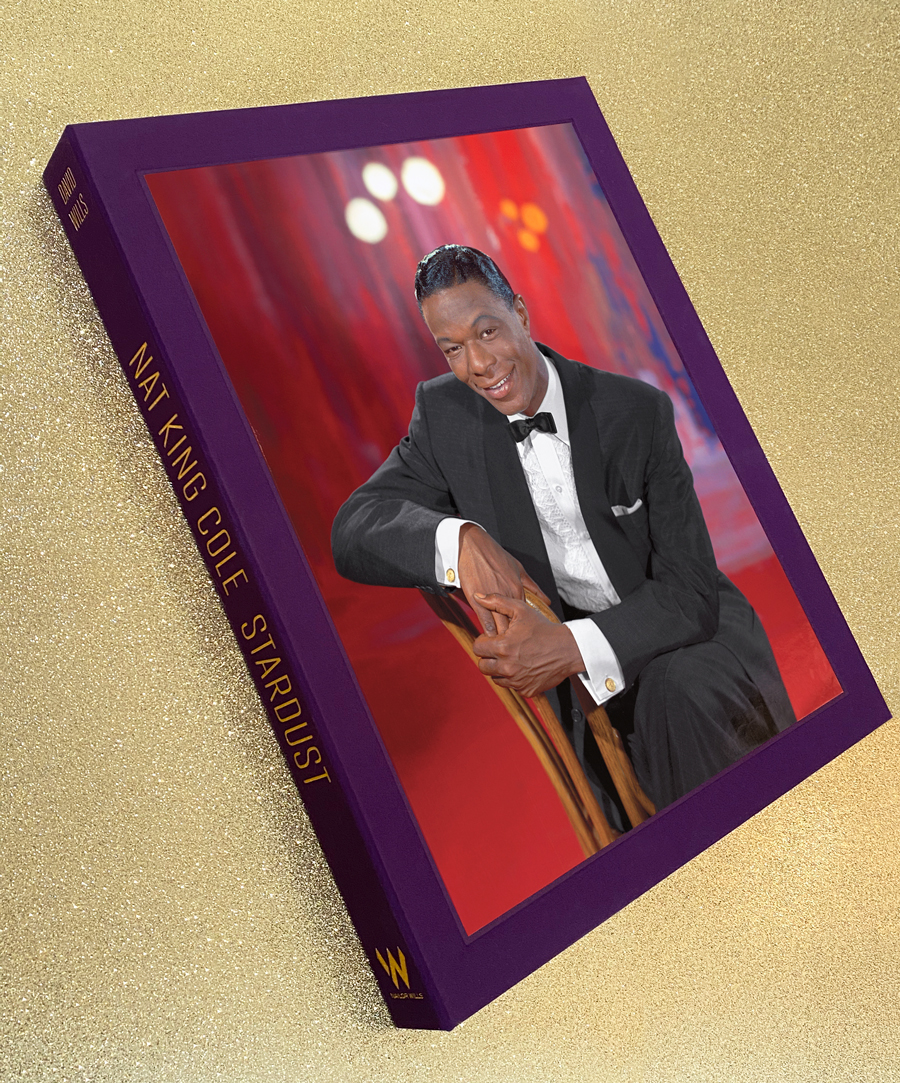

Produced in a limited edition of 1000 copies, the volume is super luxurious and housed in a clamshell case with a soft cashmere lining. It comes with a limited edition 11×14 inch photographic print from the Capitol Records photo archive.

Congratulations on such a beautiful book, and congratulations on Nailor Wills Publishing. We are big fans of many of your previous books such as Veruschka, Ara Gallant, Hollywood in Kodachrome, and Seventies Glamour to name a few. What brought you to launch your new publishing company and to start it with a book on Nat King Cole?

Thank you for the kind words—that’s so nice. The main reason my partners and I started Nailor Wills Publishing was to produce books of exceptional quality. I have loved books since I was a kid, and even used to make my own books out of butcher’s paper when I was in primary school. For many years I had noticed that publishers were becoming increasingly more concerned with profit margins than they were with how well the books were made, particularly regarding materials, paper quality, etc. I completely understand this of course—as it’s a business—but when the day came that I found myself having to fight for a book to be shrink-wrapped, I knew it was time to leave and do my own thing. The opportunity to do a book on Nat King Cole actually fell into my lap, as around the time we were considering starting the company the representative for Nat King Cole’s family approached me about doing a book. I was so fortunate.

You collaborated with Nat King Cole’s daughters who were very young when he passed. What did they bring to your attention about Nat that you were personally unaware of?

Casey and Timolin were only three years old when their father passed away. Therefore—their personal memories aside—they have primarily come to know him through family photos and stories told to them by their late mother, Maria. What they brought to my attention was the generosity and humility of their father, and the radiating effect that had—still has—on anyone whose lives he ever touched. Casey and Timolin have done an extraordinary job carrying on their father’s legacy with their non-profit foundation Nat King Cole Generation Hope, which provides access to music education for children with the greatest need.

How long did it take for you to put the book together?

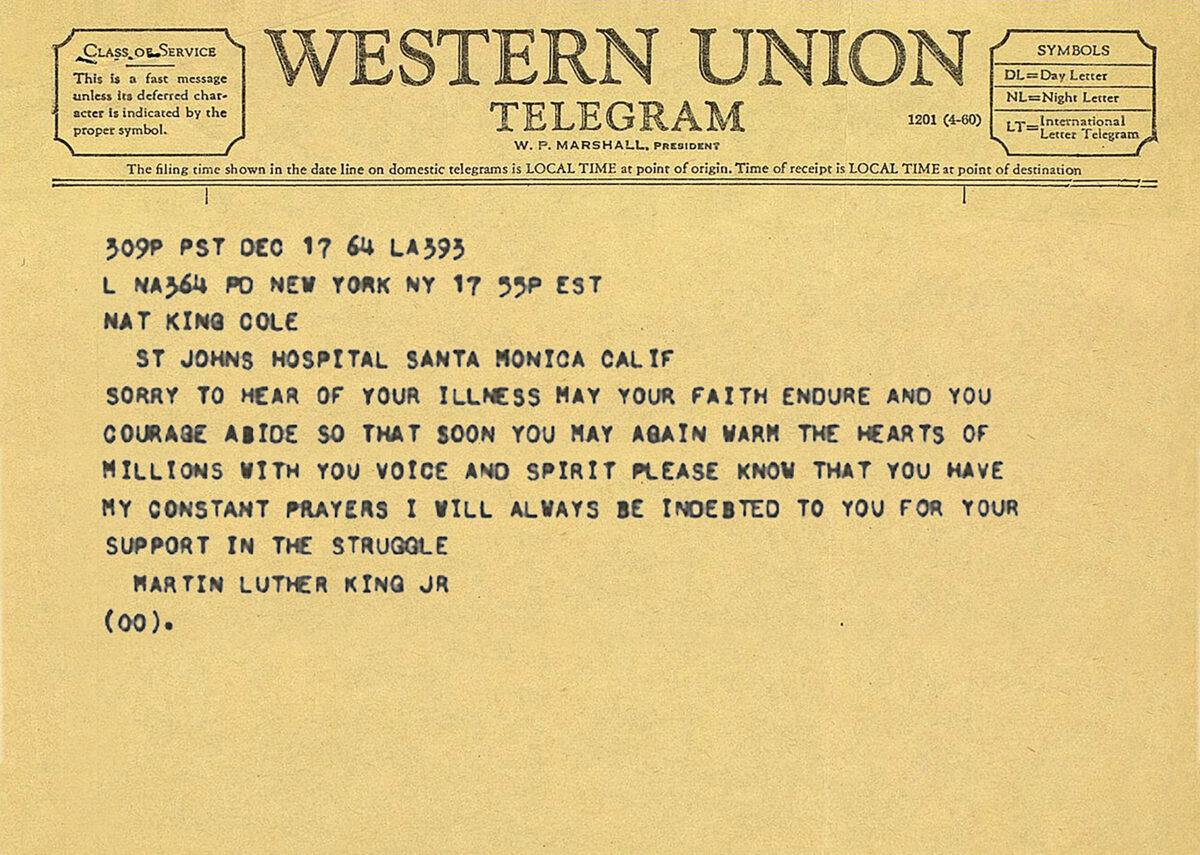

Approximately two years. Johnny Mathis wrote a beautiful introduction for the book and Casey and Timolin provided a heartfelt foreword. As the book is extremely large in format—14×17.75 inches—it was very important that the images be of the most exceptional quality. For this reason, we went back to original negatives, transparencies and photographs. In some cases, images had to be scanned and laboriously cleaned and color corrected to restore them to their original vibrancy. Capitol Records was wonderful in their understanding of our need for first-generation source material, and the book contains many never-before-seen or published images from their archive. Also, Nat King Cole: Stardust includes rare personal letters and telegrams from President John F. Kennedy, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, President Lyndon B. Johnson, Jackie Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Where does the title Stardust come from?

“Stardust” is my favorite Nat King Cole song, and it just seemed an apt title for the book—a metaphor for the magic of his star presence and the soothing quality of his voice. The song has such a serene, dreamlike quality. Every time I hear it I feel like I’m being sprinkled with fairy dust and lullabied by a beautiful whisper. Cole’s producer, Lee Gillette, urged him to record the standard, composed by Hoagy Carmichael, in 1957. Cole initially resisted, even though he had been singing it on stage since 1954. He considered the number to have been covered, and well, by Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and others. He did one take, and subsequently sang it on the October 1, 1957 episode of his TV show. The single went to #79 on the US pop chart, #24 in the UK, but grew in status over the years to become nearly everyone’s preferred version. The poignant strings introduce Cole’s mellow tones: “And now the purple dust of twilight time. …”

Nat started during the Big Band era; what set him apart in those days from other acts?

Having idolized jazz pianist Earl Hines as a teenager, Nat intended to follow his example. Just twenty in 1939, he formed the Swingsters, and played against the prevailing trend of Big Band swing with his three-man (piano, bass, and guitar) bebop. They had their first success in 1940, when Nat’s vocal track was included on their recording of “Sweet Lorraine.”

What was Nat’s first huge hit song? Did Nat write his own songs or was he performing hits of the times written by others?

For Decca’s “race records” label, Sepia, the group recorded Nat’s own compositions “Gone With the Draft” and “That Ain’t Right,” highlighting his exceptional jazz piano skills; the latter topped the R&B chart in 1942. They signed with new company Capitol Records that year, and as The King Cole Trio, scored with another Cole tune, “Straighten Up and Fly Right” in 1943, followed up with “(I Love You For) Sentimental Reasons” and “(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66.” Encouraged by wife Maria, Cole evolved into a popular music vocalist, soon recording love songs—a notable first for a black male singer. An example would be “Mona Lisa,” arranged and conducted by Nelson Riddle in 1950, which was a B-side that turned into a huge hit—five weeks at #1 on the Billboard singles chart—and won the Oscar for Best Song. This was after “The Christmas Song” and “Nature Boy.”

Did Nat experience much racism performing in clubs in America during those times? I read that he was attacked while on stage by a mob of white men; can you tell us a bit about this incident?

The King Cole Trio played mostly black clubs in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City, staying in separate but not equal accommodations. However, after one hotel refused Nat and Maria their reserved rooms, he sued and was awarded reparations and damages.

The crucial incident played out in Birmingham, Alabama on April 10, 1956, in front of a white audience, which was infiltrated by members of the KKK, seeking to harm, even kidnap, Cole. Mid-performance—Nat at the piano—several of these men rushed the stage, grabbing him, and injuring his head and back. Musicians were assaulted as well as Cole was hustled backstage, and the attackers escaped. Nat returned to address the audience, saying he would not continue the show, and how shocked he was since he simply wanted to entertain. The next night’s performance, for a black audience, was canceled, and Nat vowed to never return to The South.

Cole made incremental moves to confront discrimination in Las Vegas. Initially forced to room in the “negro neighborhood,” he later parked a trailer in the back parking lot of the hotel while playing its showroom. His white manager stayed in the hotel. Nat then used his leverage as a Vegas draw to secure rooms, though segregated, for him and his band, as long as they did not enter the casino, dine at the restaurants, or use the pool. Starring at the Sands Hotel, he was able to insist on full accommodations and access. There was also the controversy over his buying a house and moving into a “residential covenant” neighborhood in Los Angeles in 1948: a battle he and Maria won.

What do you feel was Nat King Cole’s most significant contribution to the civil rights movement?

He brought people together with his music. For millions of white Americans Nat King Cole was their first experience of a black person being part of their household, their daily soundtrack—whether it was watching him on TV or listening to his records. Also, just by being himself, he broke certain stereotypes unfairly placed on black people through decades of injustice. He was sophisticated, he was elegant, he was charming—he was extraordinarily talented. Some may have criticized him at the time for being a white person’s idealized version of what a black person should be. But I don’t agree. He was just himself—a beautiful and refined human being. One of the most profound statements Nat King Cole ever made was: “The important thing is for negroes and whites to communicate. Even if they sit on separate sides of the room, maybe at intermission a white fellow will ask a negro for a match or something, and maybe he will ask the other how he likes the show. That way, you have started them to communicating, and that’s the answer to the whole problem.”

Did Nat have a close relationship with Martin Luther King, and did he participate in helping Dr. King fight racism, and bring about justice and equality?

I don’t know if they were close, as they were both highly scheduled, in demand across the country. They of course knew and highly respected one another. Nat could provide entree to celebrity and Dr. King could count on his financial support as Nat was not comfortable making speeches or marching in the spotlight. He had faith in building connections and understanding between the races, and did state, in his offstage, soft-handed way, “Dr. King’s fight is my fight.” In addition, Nat had a genial rapport with Eisenhower; supported JFK, who thanked him publicly; and visited LBJ at the White House to offer advice during the controversies concerning the Voting Rights Act.

How did Nat King Cole go from his successful singing career to appearing in movies? How many movies did he make? Was he under contract as an actor at one of the big Hollywood studios?

In the ’40s and early ’50s, Cole starred in quite a few musical featurettes. As his fame grew, studios capitalized on his star power in small roles, essentially played himself—for example as a club pianist/singer, establishing the mood, in the LA noir The Blue Gardenia (1953). Cole’s career as an actor climaxed in 1957 with Sam Fuller’s China Gate, in which he convincingly played Goldie, a soldier of fortune, near the end of the French-Indochina War. His only lead role, as composer W.C. Handy in St. Louis Blues, co-starred Eartha Kitt, Cab Calloway, and Ella Fitzgerald, but made little impression on critics and audiences in 1958, and no studio contract was forthcoming. Nat played a singer in the suspense drama Istanbul (1957), and a club owner in the social/racial melodrama Night of the Quarter Moon (1959), which was never released in The South. His last movie role placed him in the Wild West with Jane Fonda and Lee Marvin for Cat Ballou, released after his death in 1965. As Sunrise Kid, a Greek-chorus-type troubadour, he “narrated” the film, singing verses of “The Ballad of Cat Ballou.” Several times Cole was called upon to lend his authority, tone, and bankability to the recording of movie theme songs—my personal favorite being the Joan Crawford melodrama Autumn Leaves (1955).

Nat was featured on TV, radio, and film. How was he able to break through and be successful and accepted in all of these medias?

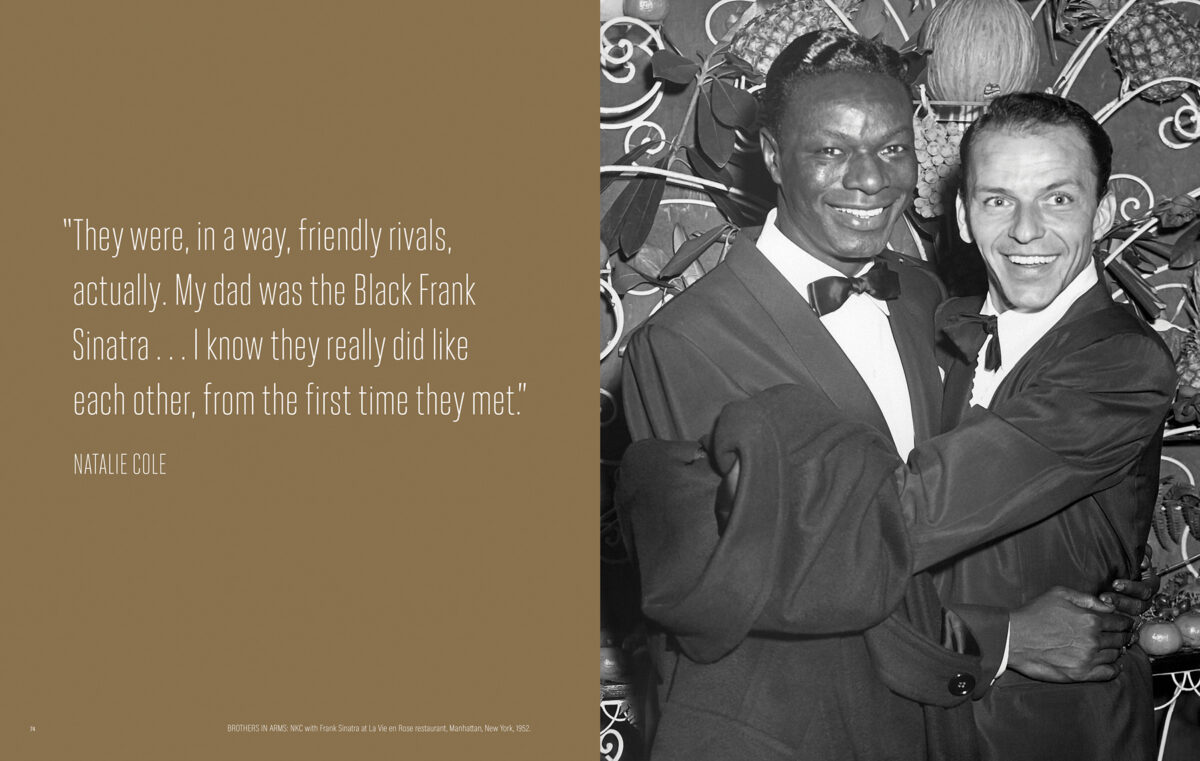

Even as a praised jazz man in the late ’30s and early ’40s, Nat came across as more than a keyboard talent. When fervently urged to sing as well as play, that smoke-through-silk voice demanded attention, well before he was prepared to accept it. As a pioneering crossover artist and hit maker at Capitol Records, he was compared favorably to Frank Sinatra, his label mate. Nat’s TV show, the first for a black singer, familiarized the American public with a person of color, right in their living rooms, singing of love and romance. The program, though it lasted just over a year, gave many households their first weekly exposure to a black host. It was a uniting experience. Nat became a premiere attraction across the country—singing at the most posh venues—and an international star, touring the UK and Europe, meeting royals, traveling to Japan, Central and South America, Cuba, and Australia, where he was received with Sinatra or Elvis-like fandom.

Nat was said to be the Black Frank Sinatra. Did he have a good friendship with Frank?

Sinatra loved talent and deplored discrimination; Nat personified one, and was a target of the other. The two men were friendly rivals, but Nat was too much the polished yet shy gentleman, to be part of the raucous Rat Pack. Frank, who was always at the ready to step in, helped Nat make a safe exit out of Birmingham in 1956, swiftly arranging a charter flight.

Nat King Cole was always so beautifully dressed and had such extraordinary style. Do you see him as a contemporary style icon?

Absolutely. In fact, the term “natty dresser” was apparently coined in reference to Nat. His personal style, in particular—sleek polo shirts paired with super-slim trousers and dark suede shoes; luxe cardigan sweaters in neutral shades; precise blazers in blue, black, or gray—has had considerable influence. He’s now a sartorial role model: dapper, debonair, snappy in sportswear, elegant in black-tie. Always sharply tailored—usually by “tailor to the stars” Sy Devore—even in the studio, his tweed porkpie hat and black horn-rim shades are now considered the essence of ’60s cool.

What song do you think is the song that is most associated with that legacy?

Thanks to daughter Natalie’s 1990 tribute album, the song that has become most identified as his alone, is “Unforgettable.” The virtual video duet was, at the time a technological triumph, a Grammy winner, and a labor of love for Natalie. The 22-song CD engendered a new fan base for the classics of Mr. Cole, whose rich discography had fallen out of favor in the ’70s and early ’80s before being revived as background vocals in film and episodic TV.

So many people refer to him as a true gentleman, a trailblazer, and someone who commanded respect. What do you feel his ultimate legacy will be?

I think his daughter Timolin said it best: “Our father was a pioneer who transcended color and race.” There’s something about Cole’s voice that reaches into your heart and just stays there—it’s a warmth, a comfort. Being able to extract emotion through your art is an extraordinarily powerful gift. Music is healing, and Nat King Cole was—still is—one of the greatest healers of our time. Ultimately, at the core of his legacy was Mr. Cole’s hope to unite, to convey joy, to give pleasure—as he said, “to make people happy.”

SIGN UP HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION AND TO ORDER THE BOOK

About the author (2021)