STUDIO VISITS – CAMILLA ENGSTROM

Swedish-born painter Camilla Engström’s work explores autobiographical issues through her lens of humor and figurative expression. With a third solo show that opened earlier this year at Brooklyn’s Cooler Gallery, Engström opens up about processing her anger through phallic symbols, her cartoon-like characters, and her quest for inspiration.

Portrait Photography by Tiffany Nicholson | Interview by Haley Weiss

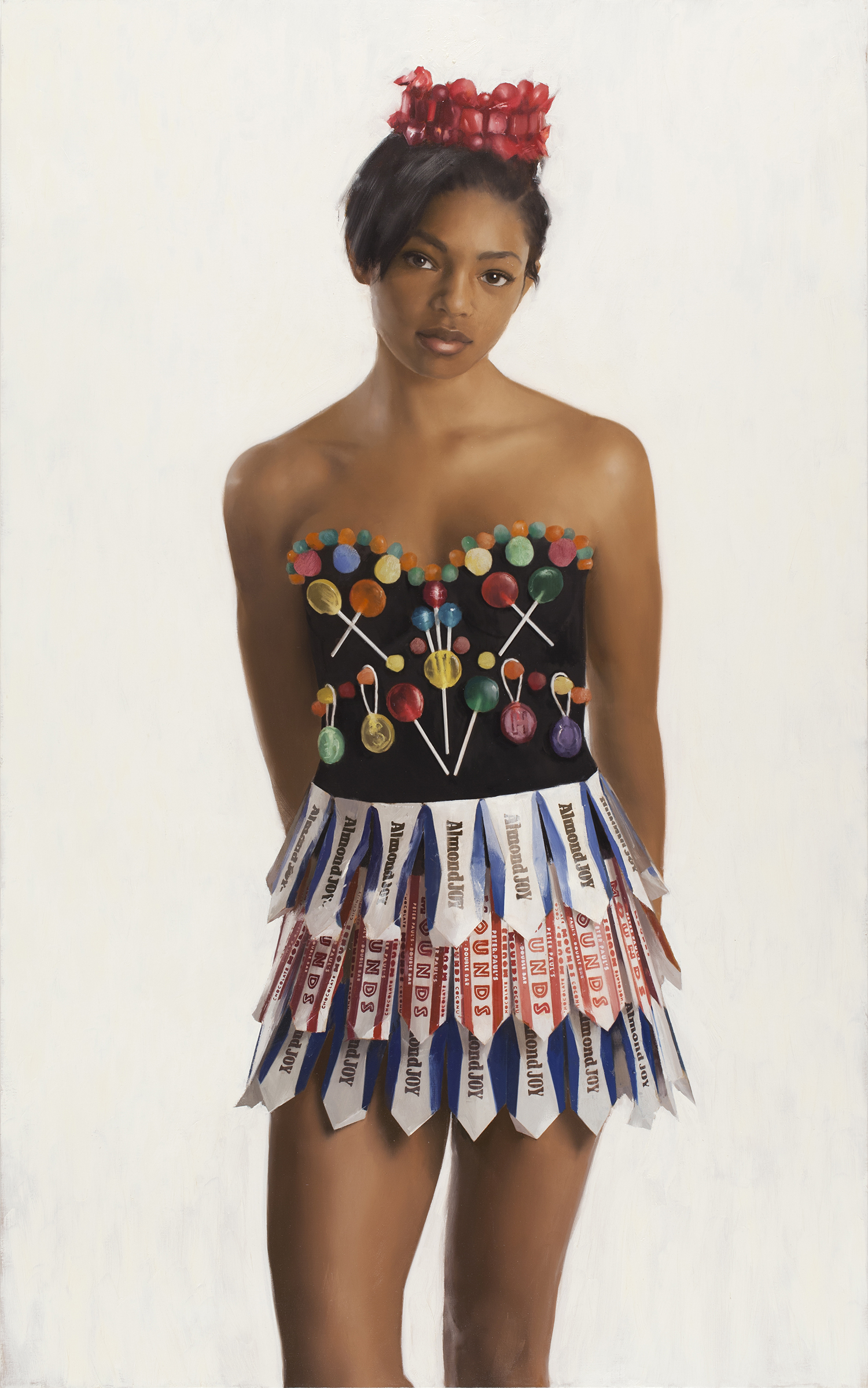

Dress and shoes by J.W. Anderson

If Camilla Engström were to make a self-portrait, she would draw a rollercoaster. That’s not to say the 28-year-old artist from Örebro, Sweden is out of control; in fact, she’s in tune with her emotions — the ups, downs, and contortions in-between. From moving to New York in 2011 to study at the Fashion Institute of Technology, to dropping out in 2013 to pursue a broader art practice, trusting her creative impulses has given her the freedom to build a body of work that includes drawings, paintings, apparel design, and sculpture. In recent months, it’s also meant accepting that she doesn’t know what she’ll do next; when we visit her Brooklyn studio this fall, for example, she says that she’s simply been “releasing pressure” by painting.

“I don’t even know what I’m making,” she admits, assessing the colorful canvases that fill her wall, although there’s one obvious commonality. “It’s just a lot of sausages,” she adds with a laugh. One painting features a long and artfully twisted sausage, while another shows a sausage being stepped on by multiple feet. This new subject is unsurprising given Engström’s history of irreverent, humorous compositions. She explores sexuality, consumption, and the banal (e.g. bathing, cats) with a wink. It began with her roguish alter ego, Husa, the curvy pink figure who’s appeared in Engström’s pieces since she was first sketched years ago. Husa has many activities, including reading or drinking wine while naked on a picnic blanket, and sitting in a reclining chair, drooling, with food resting on her lap. And she, like her creator, is also capable of change; in 2016, at what Engström describes as a “zen” time in her life, she depicted Husa as a contemplative figure. The result was Faces, Engström’s first-ever solo show at Deli Gallery in Queens, in which Husa appears in various states of undress, transforming beneath a sun-like orb. In one painting from that series, Husa disappears entirely, leaving her dress suspended in mid-air, as though she’s transcended the bodies and cultural norms Engström so often points to in her work. It turns out that with an open approach like Engström’s, one recurring figure can address both the commonplace and the ecstatic.

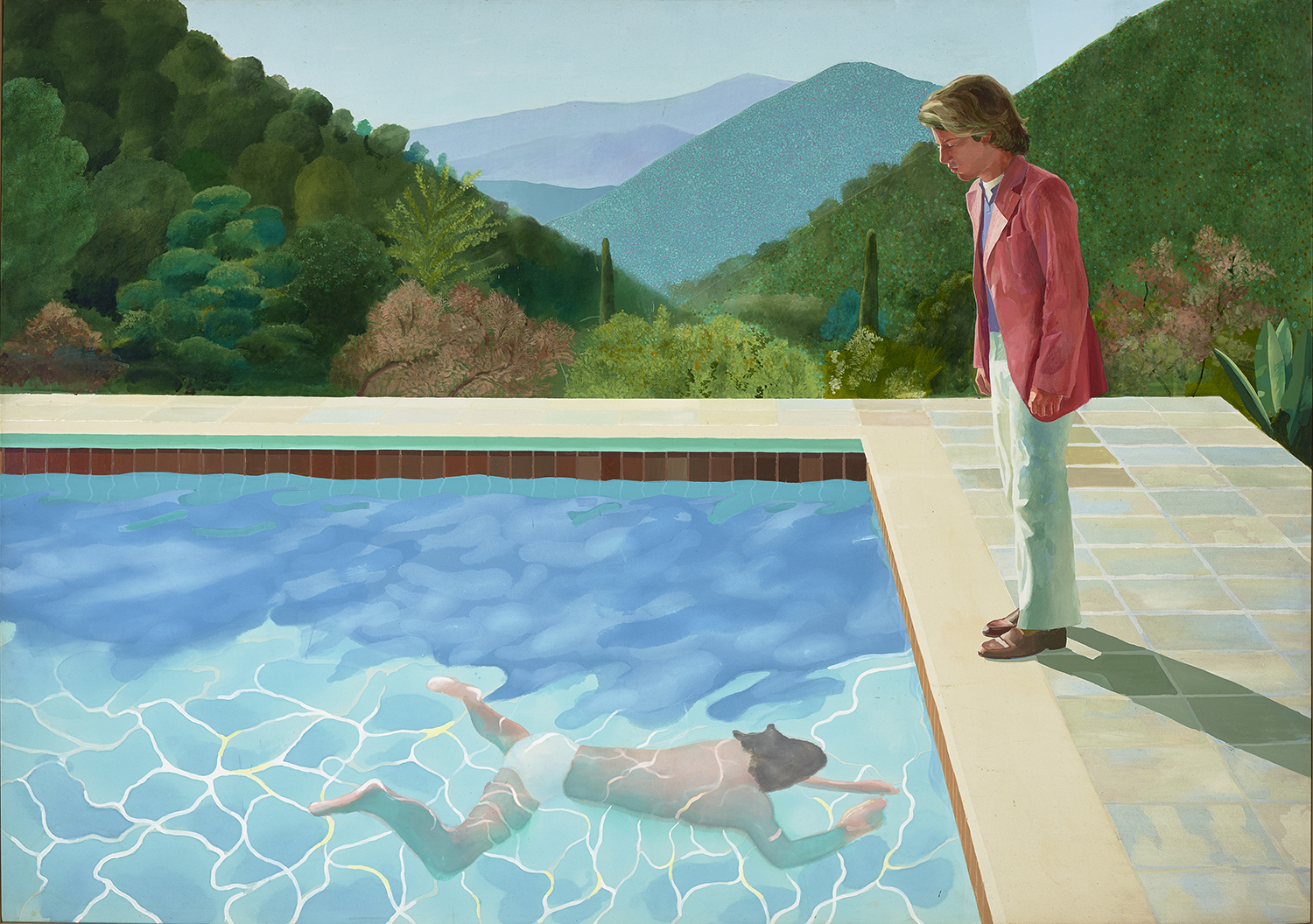

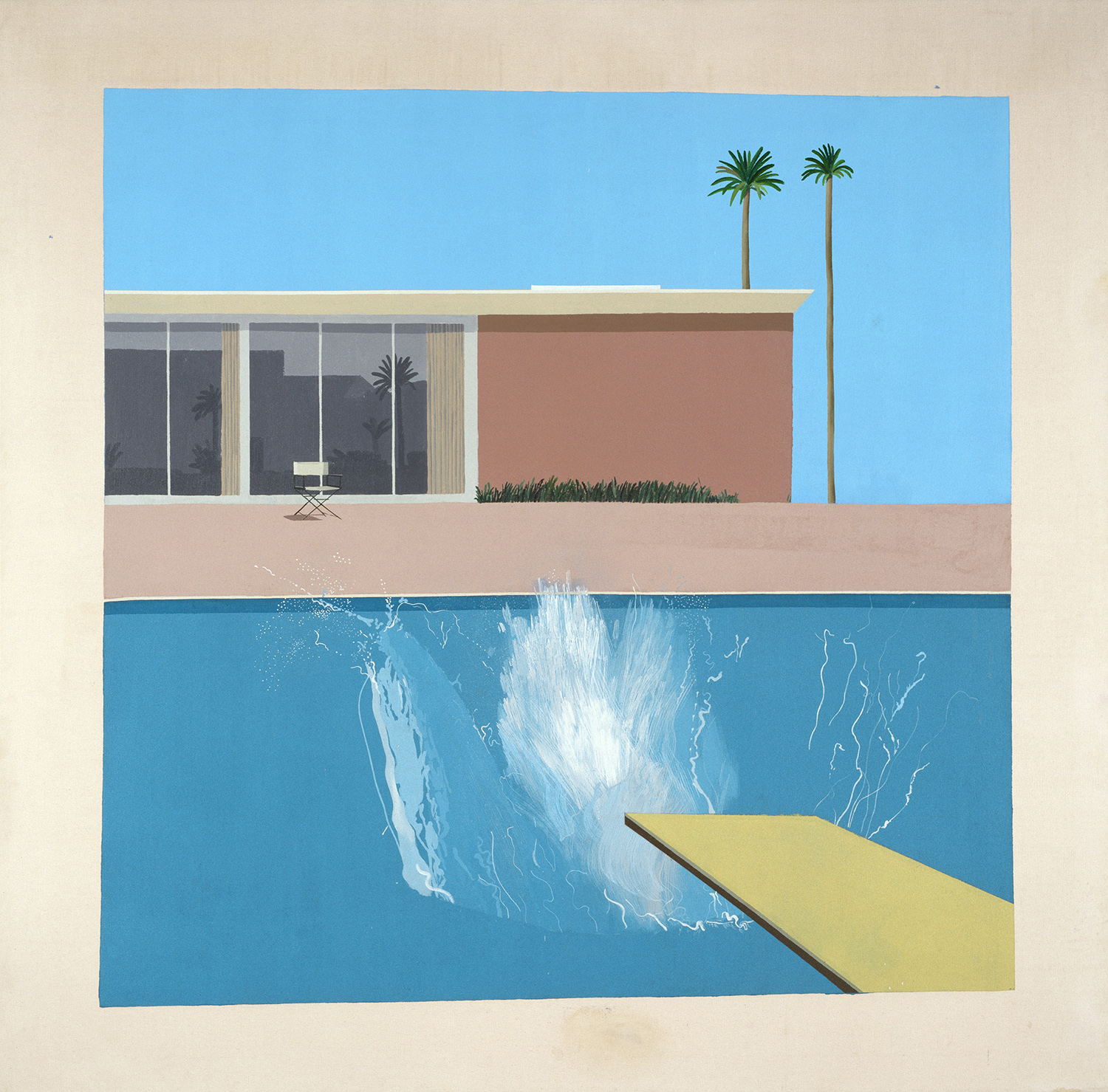

Big Bear, 2017

Big Bear, 2017

You’ve described drawing in the past as not actively thinking; you’re just letting it out. Are you surprised by what you make?

Yes, sometimes. I like to start small because that’s less intimidating. That’s usually when I’m like, “Whoa, what’s going on in my head?” For the last few months, I’ve been kind of controlled in the way I’ve been painting. Now I want to be a little bit looser I think, which is frustrating because I wish I could paint the same way and stick to it. I just can’t.

When you’re painting and you’re stricter, does that happen naturally or is it a conscious decision?

It also happens naturally. I think more before I make the painting. Whereas these messy ones, [gestures to sausage paintings] I don’t really think at all, which is nice. I like both ways. With the more controlled ones, I definitely feel like I’m more relaxed, and even though I’m thinking more beforehand, I’m just focused, getting the paint in there. Whereas painting the messy ones, I feel sweaty afterwards; it’s almost like an exercise. I try to make them really quick and I try to make many of them.

Why do you think sausages are reappearing, if you were to do some self-analysis?

Before I used to paint dicks a lot. [Engström published A Book of Dicks in 2016.] I wanted to make a new dick book. I feel like I have so many dicks in my brain; I need to get them out there. I like to turn them into sausages because I feel like I can’t paint the dick. I’m just so mad at dicks right now. Sausages are easier for me to handle. They’re less intimidating.

You said you’re mad at dicks. Could you elaborate on that? Is that a cultural frustration, one with politics, or—

I think it’s politics to be honest. When every hurricane, every disaster happens, I’m just playing with a dick [in my work]. I feel like if we backtrack, it’s all the dicks’ fault. I was just reading about Harvey Weinstein and I want to destroy him. Now he’s destroying himself. How could he do that for so many years? It makes me want to cry but it also makes me so mad. It’s all of that coming to me at the same time.

It also makes me think about when I’ve been sexually harassed by men, and it makes me think about my sister, who’s 10 years younger than me. I just realized, I never said to her, “You have to say no.” I never had the conversation with her: “This is how you deal with a bossy guy.” She’s almost 20 now, and she’s in college and she studies international finance. There are a lot of men there, and they drink and they party all the time.

I was watching her Snapchat almost having a heart attack. That’s when most of that shit happened to me. You’re drunk, you’re with guys, and you feel pressure to be accommodating, and then it all goes downhill. I just texted her today: “We need to have this conversation. You are the boss over your own body and I see how you’re with guys all the time. I’m sure most of them are nice, but even the nicest guy, if he wants something from you and your body, you need to be able to say no.” I wish that our mom had told me that because I feel like maybe I would have been more brave and not so terrified every time. I’m definitely frustrated with the dick this year. I’m hoping next year it will all be about the beautiful vagina.

Do you remember your first drawing of Husa?

Yes. I remember I was looking at a lot on Pinterest at the time — because that’s what you do when you work in fashion, you sit on Pinterest all day (laughs) — and I was looking at all of these sculptures. I wanted to paint a round figure because I had been painting so many fashion illustrations — I was also very influenced by Picasso. Then I started to paint a round figure but it was very serious. It just didn’t feel like me. I was painting her over and over and over again. Then finally I just gave her a face, and it made me giggle, because I could see it come to life. It just all came together and I was like, “Okay, this is my friend that I’m going to paint for a long time.”

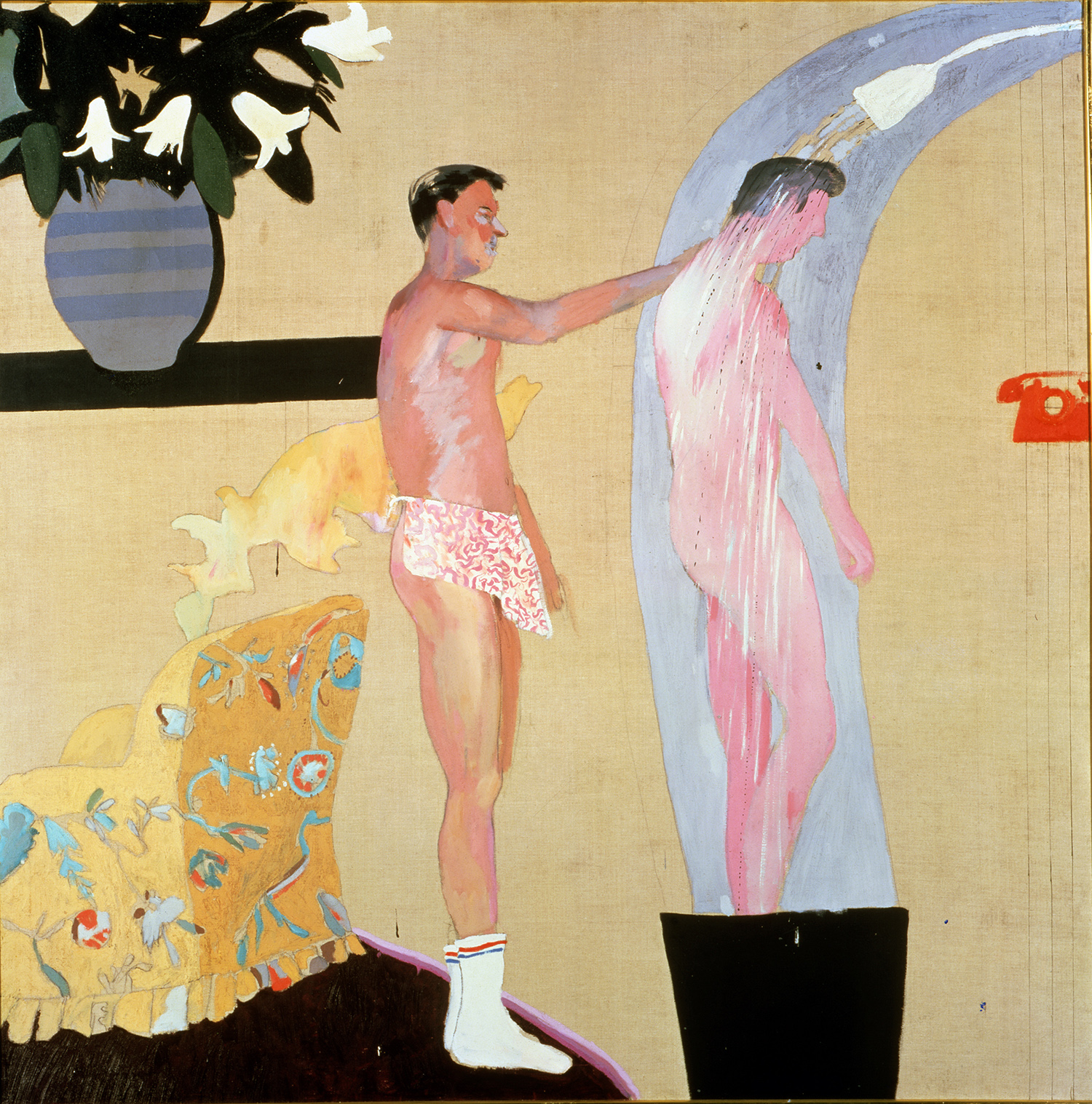

Hairier and Hairier, 2017

Hairier and Hairier, 2017

Dress and shoes by J.W. Anderson

When you moved from fashion to being an “artist,” what was that decision like? Were you tired of fashion; was there a certain attitude you wanted to get away from; what was it?

I was frustrated with fashion. I felt like I was so creative — a typical millennial kid that’s just like, “I deserve more attention.” I wasn’t good at dealing with technical stuff. I could create things, but no one wants the creative person because they already have that. I felt like I was going to explode because I had so much to give but I couldn’t. There was never an opportunity. Then the tasks they gave me were easy but so unfulfilling.

I still love fashion and I love clothes. I think I have like a healthier relationship to fashion now. I feel more relaxed about it. When I left fashion, I didn’t want to leave completely. I still love working with textiles and I did this little embroidery thing with the Swedish brand called Monki; we did a clothing collaboration. I’m sure there are some artists that really don’t want to see their work on clothes, but it makes me so happy.

I know a lot of people won’t be able to buy my work — I could never buy my work — but they could buy a T-shirt. It makes me so happy to see someone wear my T-shirt or tote bag.

What are you inspired by at the moment? Is there anything you’re reading, listening to, seeing?

I took a break for two weeks; I went to Japan. I just got back. I felt like going to Japan was going to change my life and that I was going to come back and be like, “This is what I want to paint now.” It was definitely inspiring to be there, but it just made me more confused.

Had you been there before?

No, it was the first time. I love Yayoi Kusama so I wanted to go there and see her work and see what kind of environment or culture she grew up around. I wanted to experience it. I came back and I was like, “I don’t even know what I want to make anymore.” Sometimes I’ll go see a show and I’ll be so inspired to make something, so it was super frustrating. I’m still inspired by Kusama a lot but it’s almost like I looked at her work too much. I think I need to step back a little bit.

I went to MoMA; I looked at the Louise Bourgeois exhibition. I tried to feel something and I just didn’t. Then I picked up ArtForum; I went through it and I just thought, “Fuck.” You know when you’re inspired, it’s just this feeling, and I haven’t had that feeling yet. I’m going to push myself and try to be inspired by myself. I hope it comes soon because I really need to work — to work with a confidence.

Hairier and Hairier, 2017

Hairier and Hairier, 2017

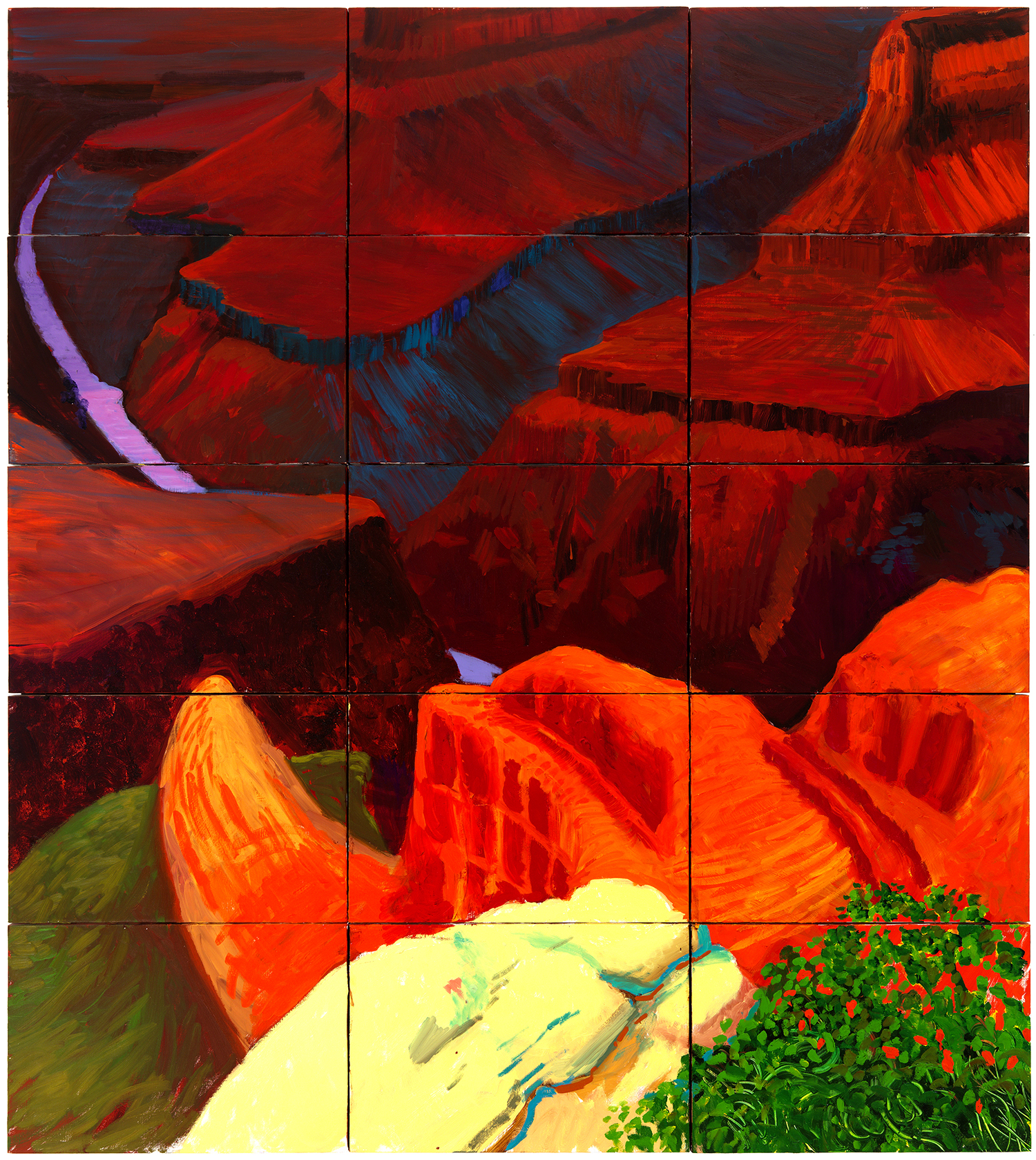

Food Coma, 2017

Food Coma, 2017

When you say you need to work, you need to as in you have to be making things?

I feel maybe like a guy that hasn’t had sex in a long time; I feel like the energy’s there, the need is there. I’m so frustrated. I feel like I can’t create, like something’s missing. I’ll get there. I reach this point probably like five times a year. I’m okay with it.

Do you force yourself to paint every day? What does your day-to-day life look like?

Yes, I force myself because I feel like I have the energy. If I don’t have the energy, I don’t even try. I just stay at home and cuddle with my cat. But now, because I have all this amped up energy to paint, I force myself because I feel like maybe I’m thinking too much. Maybe I just need to paint and then it will click, and that’s where I’m at right now. I’m hoping that maybe tomorrow or the next day something’s going to happen. We’ll see.

When was the first time you can encountered a work of art while you were growing up?

I grew up with this huge painting that disturbed me so much.

In your house?

Actually it was in my grandfather’s house. It was so big, it had to be the centerpiece. It was dark blue and it was a forest at night and there were animals running away. I remember at night I would always run past that painting, because there was this owl sitting in the middle with its bright yellow eyes staring at me. But then during the day, it was right next to the couch and I had to deal with that painting. When my grandfather died, it moved into our house in the same spot towards the couch. It was really bizarre.

I knew there was something special about that painting, that it wasn’t just a painting or a picture on the wall. It was something that really, really bothered me. It made me feel something, and knowing that a piece of art could make me feel something, that was the first time I understood that it was art, and it was important. Being around that painting for so many years, even the scale of it… It’s always going to be with me.

Dress and shoes by J.W. Anderson

Hair and Makeup by Agata Helena @ agatahelena using NARS cosmetics, Art Direction by Louis Liu, Editor Marc Sifuentes, Production by Benjamin Price

–

All art work © Camilla Engström images courtesy of the artist

For more information visit camilla-engstrom.com