MICKALENE THOMAS

With a dedicated studio practice that spans multiple disciplines, Mickalene Thomas explores and challenges societal understandings of beauty, femininity, and identity through her work. Known for her bodacious collage-style, rhinestone-clad paintings, the refreshingly-uncontrived, artistic mastermind is the embodiment of chaos and control.

Photography and Interview by Dustin Mansyur

Unisex Suit and Shirt by Vivienne Westwood, Sunglasses Artist’s Own

The ground-floor, sprawling, warehouse studio that Mickalene Thomas runs is anything but the archetypal cluttered creative hub one might picture when visiting an artist’s studio. Instead, its organization suggests a need for clarity and control required for the artist to create. Small-scale collages, paper and material remnants drape across a single work surface like a patchwork tablecloth, with a pair of scissors propped suggestively on a roll of electric green tape as a centerpiece to its cacophony of color. In a far corner of the studio, a heavy vinyl curtain is swagged aside revealing a space reminiscent of a car-paint room, the color-spattered work table in the center is cleared with equipment tucked away. Adjacent to it, a barrage of carts are trolleyed up neatly, loaded like pack mules with a rainbow of oil pastels, paint tubes, mixing utensils, and a spectrum of boxed rhinestones. Mickalene pushes one with a generous smear of cobalt paint and a pair of knives towards an unfinished piece that she’s “mucking up”, its wheels singing furiously like an operatic aria of the paint’s destiny. Flanking the walls, large-scale canvases of works-in-progress commune with one another, while awaiting canvases are filed away orderly in gargantuan cabinets. The multi-disciplinary artist needs space to breathe and listen to the dialogue of her work as it banters across the nucleus of the studio floor. A library elicit of her groovy, soulful sets offers an inviting corner to entertain studio visits, but we will stand and talk today as Thomas works on a diptych.

An alumni of Pratt and Yale and a United States Artists Fellow, Mickalene Thomas is a dichotomy of soft-spoken eloquence and outspoken intellect, a juxtaposition that feels arresting and gravitational. With a separate office space that runs the length of the studio and a quarter its width, it’s evident Thomas runs a tight ship over her studio practice and team. The role of boss aside, Mickalene Thomas is a distinguished visual artist, filmmaker, and curator whose work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally, and is housed in many permanent collections including Guggenheim, Brooklyn Museum, MoMA PS1 New York, and Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, among others. Her work embraces art-historical, political, and pop-cultural references. Employing the disciplines of photography, painting, collage, sculpture, and installation, her exploration of the complex notions of femininity challenges prevailing definitions of beauty and aesthetic representations of women.

Here IRIS Covet Book shares some studio time with the artist as she articulates on adding to the dialogue of the conventional canon of Western art history.

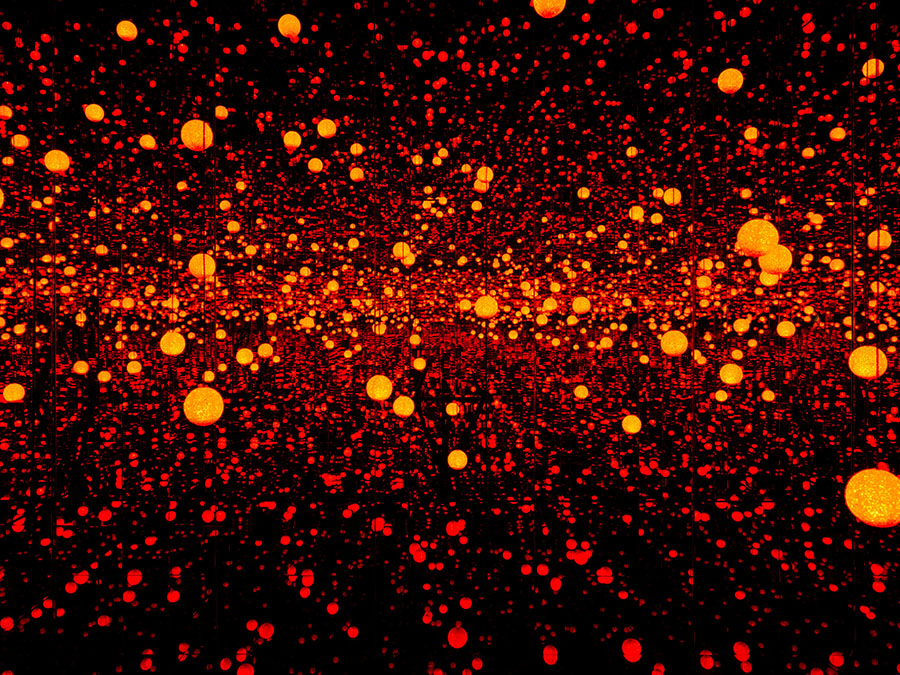

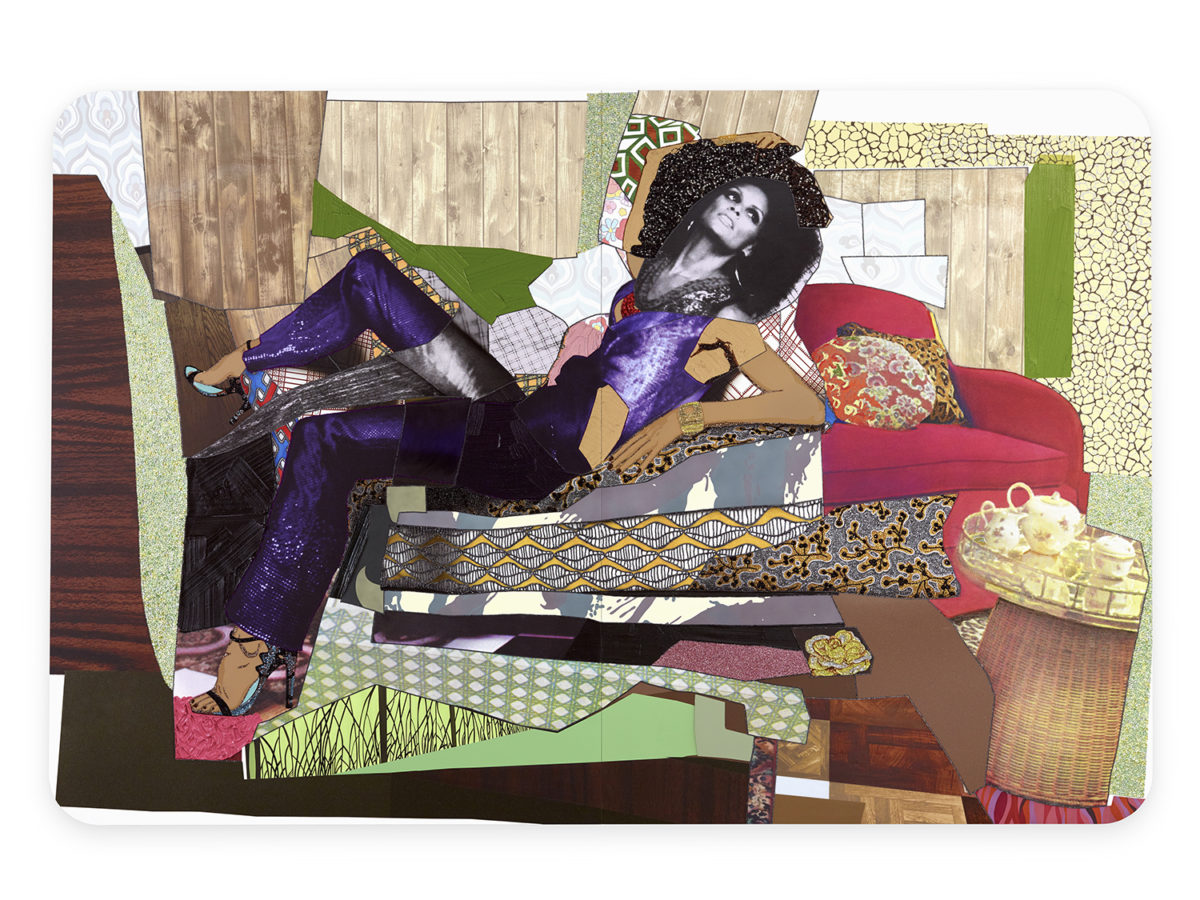

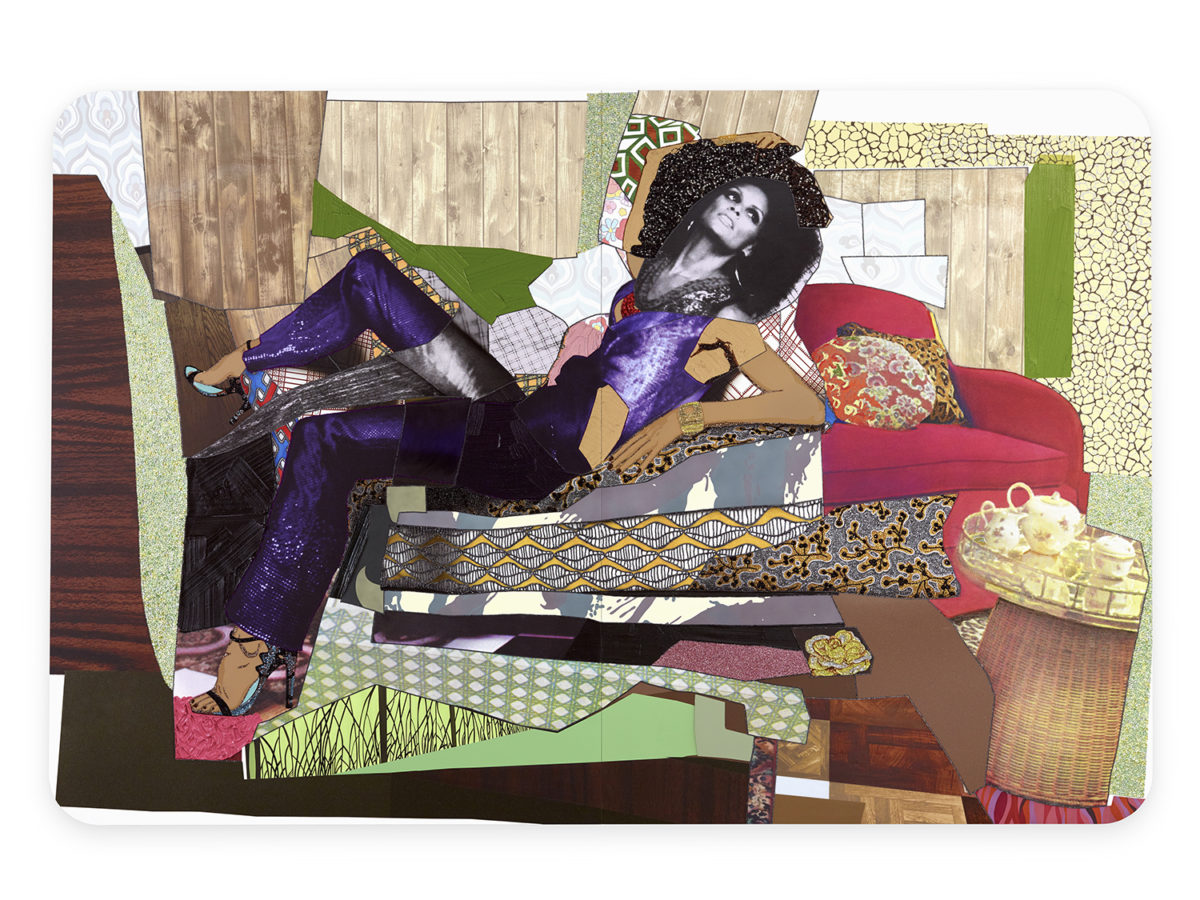

Racquel Reclining Wearing Purple Jumpsuit, 2016

Were there any influencing factors in your childhood that really helped nurture your love of art? What motivated you to pursue this as a life and career for yourself as an artist?

Being raised by an adventurous, industrious and resourceful single mother who exposed me and my brother to art at a very young age. Around the age of 7 to 12, my mother enrolled my brother and I into various art programs in New Jersey and New York. My fondest memories are at both the Newark Museum and the Henry Settlement in the Lower Eastside. In our house there was a constant engagement with art, fashion, and music. My mother’s eldest brother was a trained fashion illustrator. He illustrated for magazines and designed some record covers, as well. I loved looking at his drawings, they remind me of Bill Traylor’s work. The biggest inspiration on this “jersey girl” was New York City.

We ventured to the city on every weekend we could afford, to attend the Met Museum and to see Broadway shows, mostly Off Broadway. My mother surrounded us with her creative friends. They organized house parties and fashion shows around Newark and East Orange. She and several in her group of her friends produced these events. Their parties were called “Better Days” and one of the plays I remember was called Put A Little Sugar in My Bowl. My mom’s friend gave me the script to the play. Looking back and reading the script reminds me of Tyler Perry plays, excluding the religious banter. I guess you might say that art chose me. I’m a product of my mother’s creative environment.

You work in so many different disciplines. You do photography, collage, painting, sculpture, and installation. Presently, what disciplines are you utilizing in your work?

Including performance, video, and the other five disciplines you mentioned, I oscillate among all of these disciplines, depending on the scope of my project, the concept, or idea; eventually making a decision on which discipline is best to execute the idea. Currently, there are two main techniques that are a major thread in my work, which I use in tandem–photography and silkscreen. I employ silkscreen as a way to bring forth the photographic elements into my painting. Silkscreen is used in my work as a tool to convey that language. It’s extremely important to me that the photographic images on the painting, appear as a collaged element rather than literally gluing or pasting a photograph onto the paintings. Photography plays a primary role in my studio practice, and it’s the strongest thread throughout my work. I shoot all of my resources for my work; for found resources, after scanning, them I put them through a photographic process to claim them as my own. What excites me currently as an artist is transforming my photographic images into a painting language. Although, sometimes my photographs and collages serve as blueprints for my paintings. Now I’m thinking about how I could use these disciplines within performance. My new body of work is video based and performative. Working in film has given me license to explore the moving image as the editing process relates to collage.

Combining all these different disciplines…is it in anyway a metaphor for the complexities of your identity?

I think all of our identities are complexed, and these different disciplines provide a platform for me to navigate and explore my identities. As my art morphs and transforms, so do I as a person with my ideas and sense of self. I’m not the same person I was 10 years ago, neither is my art. I harbor various complexities in the same way as I oscillate within different disciplines. My mythos isn’t to be defined by the work that I make, in the same way that it’s an extension of myself. I can’t escape the methodologies of these disciplines because they are all pertinent for me to tell my story by any means necessary.

The strongest discipline in my work is photography. I see it as one of the most powerful tools constructing or deconstructing our identities. It’s our own black mirror, within the constructs of us having the need to constantly see ourselves instead of really seeing each other. Photography is it’s own visual language, it’s how we communicate–it’s on all our devices, it’s the new handshake, it’s the how are you today, and our third eye. I’m interested in using the photographic lens and other devices that will allow me to see myself and others.

Unisex Suit and Shirt by Vivienne Westwood, Sunglasses Artist’s Own

Where do you begin? How do you start a piece? During our photo shoot, I noticed there were several smaller collages on a work table.

The small collages are an iteration of my practice through a photographic process. I make a series of collages based on the photographs taken during photo shoots. The collages aren’t necessarily one-to-one with the paintings, they are research, resource, and a discovery into the the process of my paintings. The collages have their own strength that I try to bring into the paintings. The exploration within the collage materials allow me to be uninhabited and free of constraints. The discovery of making the collages is allowing the scissors to do it’s magic by cutting shapes and forms that tell a story with the images that I’m using. All my cut scraps are reusable for new images. I have piles and piles of images and materials, organized and chaos, colored and textured, pattern and glittered, layered and integrated. It’s exciting to think about all of those materials and how they will juxtapose with one another.

How did the rhinestones come to be such a touchstone part of your work?

I started experimenting with rhinestones when I became interested in the notions of pointillism during my time at Yale. In relation to my work, rhinestones seemed to be the most relevant material, and I realized that they provide a perfect combination of content, process, and materials not as an accoutrement. They serve to challenge my ideas of what paintings are, and can be. As my work evolved and developed stronger, the rhinestones started taking on other meanings as I expanded them into my practice.

I love that you really embraced that. Even though you referred to them as non-traditional material, you have given it this life to become its own medium, like oil or acrylic.

They are just as important as the acrylic and oil paint, the silkscreen, the oil sticks, and gestural marks. They play the same role as these materials and formalities. All of the elements or materials that I employ, represent the notions of artifice, constructed ideas, and means of how we consider adornment on ourselves and in our environments. How we can utilize and manipulate them to exude a certain quality, beauty or light. Also, rhinestones are a very interesting material to work with, the challenges are vast, and it possesses a multiplicity of ideas and notions that I feel like I could grow with as an artist. Figuring out how to use them in my paintings, but also as a material like paint is very exciting for me.

All of the collages in the interior spaces that you present within your work…I’m so fascinated by them because they look like such an interesting world to reside within. What does the interior as a subject matter mean for your?

For me, the interiors are just as important as the portraits because I think of interiors as portraitures. I think you can tell a lot about a person by the things they surround themselves with and how they live. There’s this residue of life, of cultural history, of storytelling, and all that is domestic that describes the home. How we surround ourselves to complete who we are, and the home or interior, is one of them; the landscape is another. I’m interested in how we reside within these spaces, and how these spaces tell a story of who we are.

I’m mostly trying to reference my childhood, and the environment that I found to be most comforting and inspiring as a young girl. I don’t necessarily think of it as being representative of a specific cultural or ethnic identity–while that may serve as one of the inspirations, it really is meant to reflect on the extensions of my own identity and history.

You just opened a show at Rice University in Houston that featured one of your installations. Are the installations something that you utilize as an extension of the set from the photographic process, or a three-dimensional form derived from the collages or paintings of the interiors?

Yes they are. In some ways they’re really about me trying to make sense of home. I moved around a lot as a kid, and I think that a home is the constructed safe space for families. One of the things that we identify as the “American dream” is having a home. Most people aspire to obtain home as an object of gratification or fulfillment of success regardless of demographic socially, financially, or culturally. There’s still this overarching aspiration of security once you have a home. My environments started in graduate school, when I was photographing myself. I would put up fabric backdrop to create self portraits. So when I started photographing my mother, I started adding things to the environment to formally figure out the compositions for my paintings. Overtime the blank wall was filled and covered with fabrics and wallpaper. I’ve been doing this for the past 10 years, but it’s just been the past three or four years that these environments have been recently exhibited. This part of my practice has developed and expanded into various iterations site-specifically expanding from tableaus in the corner of my studio into major installations where the viewer can activate the space.

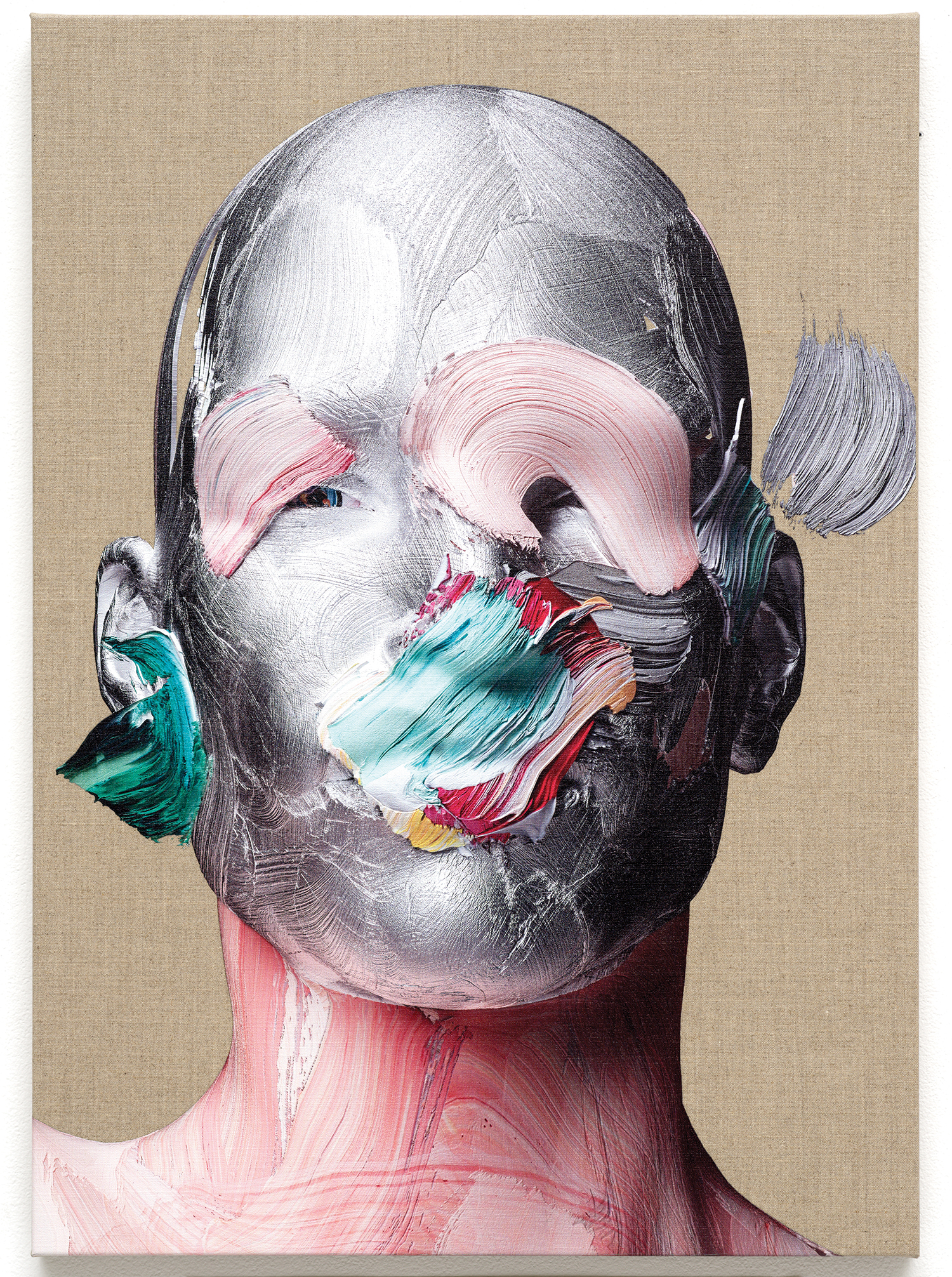

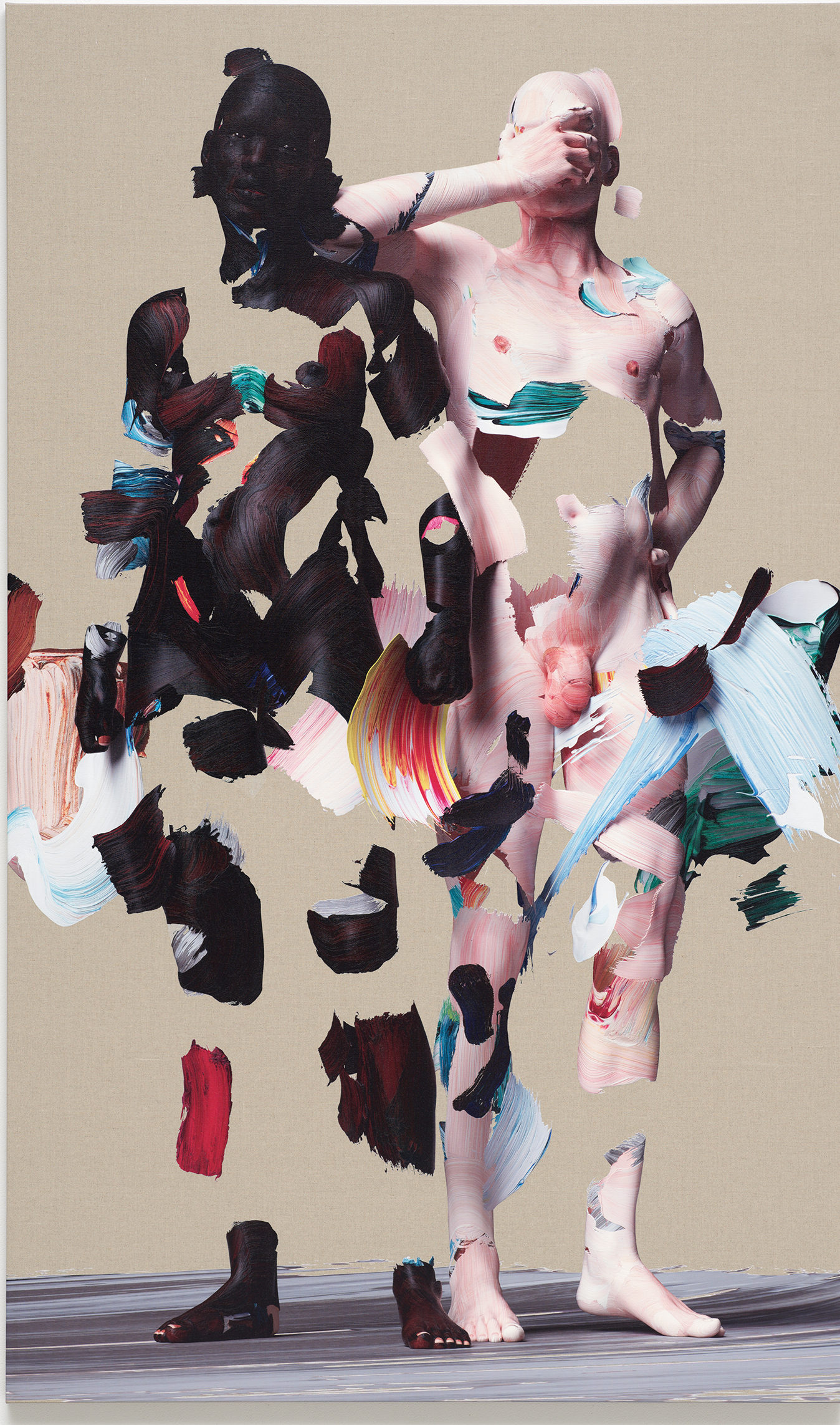

Naomi Looking Forward #2, 2016

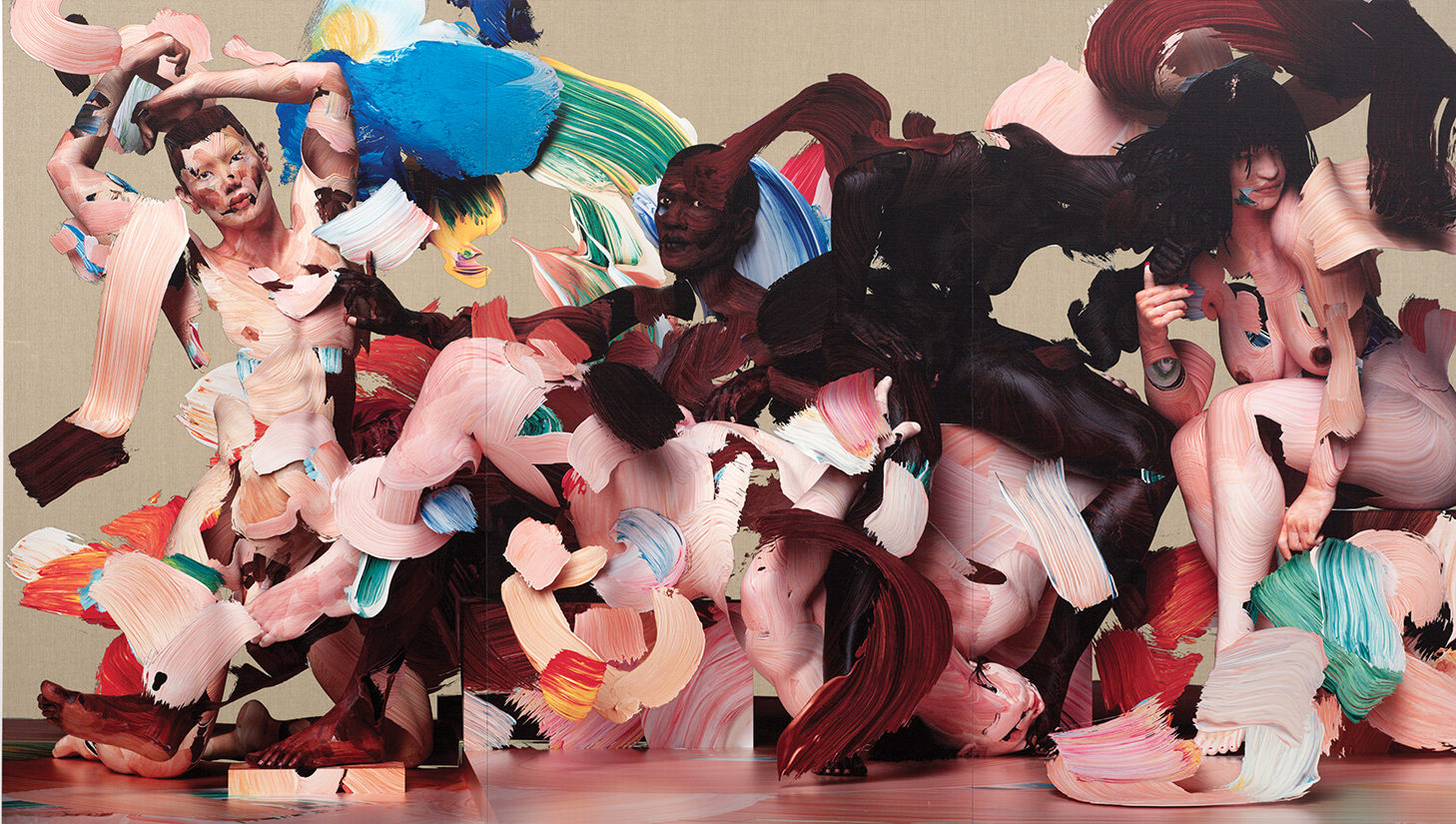

Installation at Newcomb Art Museum 2017 Variable Dimension

Do you usually have several pieces going simultaneously so that you can take a step back, think about it, and process it while working on another piece?

Yes, I work on several projects and works simultaneously. Sometimes chaotic, and then focused. Each project informs the other, allowing the works to have a strong dialogue between themselves. Sometimes I will struggle with one body of work, but then it makes sense in the other, and the works start speaking to each other, and the challenges erupt and make sense. The experience of making art is that it does not lie to you. It starts speaking to you in a certain way, and you have to listen to it. If you’re honest with yourself.

You take classical subject matter – nudes, portraiture, landscapes, interior spaces – and you re-appropriate them based upon your own cultural vantage point and perspective. When you first began your career how was the work received and has that changed over time?

It’s important to me that my work changes overtime. As I grow as a person I want my art to grow with me. It’s important as an artist to find your own voice and be authentic, and hopefully you’re adding a new dialogue to the discourse, to expand it, and to make it richer. I’m interested in using Western art historical canon by deconstructing the traditional notions of beauty within art. By bringing forth the women and beauty that have been removed from the stories, erased, and rewritten.

Art history is known to be so Eurocentric and non-inclusive.

What I’m excited about is the large circle of African American individuals as art historians: as our leaders within art history who are going to be in the position to allow these discourses to be put forth within the institutions. When you look at museums that start to embrace young African American curators, then there’s a shift because they’re entering a new paradigm that is going to allow new conversations to emerge and change in museums and other institutions. I think we need to encourage people of color to be a part of the creative field if they have that interest. There’s a huge generation of younger creative intellectuals that are coming forth that are really exciting. To me, those are the individuals I’m embracing because those are the people that are going to write our legacies and stories.

Earlier, you spoke about the photographic language acting as a kind of “black mirror”. Is that really what art is then, for you, a way of holding up the mirror to society?

I’ve read some of Lacan’s philosophy and something that really inspired me is his theory of the “mirror stage”. That our innate desire and notion of ourselves is to be validated by others, the desire is to be seen. Therefore, whena person gazes at you,it validates that existence because they’re looking at you. This idea of the gaze is very powerful and the notion of validation, and incorporating its existence into Art. Without it, we don’t see ourselves until others see us, which, in turn, gives us our sense of validation: recognizing something familiar in someone else. When we recognize our familiar selves in others, then things will change [in society].

Empathy is such a scarce quality today. How does this quality affect your work?

There’s always a greater part of empathy in artists. We are the most empathetic people. We are the leaders of the world and are capable of allowing people to become their better selves through our creativity. No matter how egotistical and selfish some artists can be, I think there’s still a greater part of empathy to making art. As an artist, we gift so much of ourselves to the world, the fiber of our existence as artists is to help others see the world through our eyes to create change.

Your work also focuses heavily on our understanding of beauty and expanding that. In fashion advertising the big buzzwords right now are diversity, inclusion…How do you think that society’s understanding of beauty is going to change in the coming decades?

The understanding of beauty today is going to become compacted with a deeper meaning of who you are, not necessarily what you look like.

You have this amazing space. It’s so huge, it’s orderly, and it’s still warm and inviting. It appears that you’re anything but the proverbial starving artist.

(laughter) I am! I am, really! I’m not starving, but I’m always hungry. I’m starving for women to sell their art at the same price point as their male counterparts without complaints of it being too expensive. I’m starving for inclusivity, and for being in the right collections, museums, biennials, on the art historian tongues, in the ear of curators, and working with the best galleries nationally and internationally. I’m starving to see more people of color and women having major retrospectives. I’m starving for auction houses to pay artists residuals.

I’m curious what you’ve had to overcome, either personally or professionally, to get to this place in your career. I feel like creative people often have a strong internal dialogue with themselves.

I persevered throughout my life. Everybody has a story, there was a glimpse of my story told in the documentary I directed about my mother in Happy Birthday To A Beautiful Woman.

What advice, then, would you share with any young person who is wanting to choose this for themselves as a life and career?

Despite your personal obstacles, it’s really important to maintain a strong studio practice and a sense of self.

Do you have a glass ceiling? What does success mean to you?

I once heard someone say, “the sky is not the limit it’s just the view”. There’s no glass ceiling for me because I’m hungry and greedy. One of the quotes that I love by Toni Morrison is “…if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.” This is success to me. I can only keep trying to do more than my best.

Hair and Makeup by Nina Soriano using Elemis, Production by Benjamin Price, Special Thanks to Susan Grogan at Mickalene Thomas Studio

All art work © Mickalene Thomas images courtesy of the artist

For more information visit mickalenethomas.com