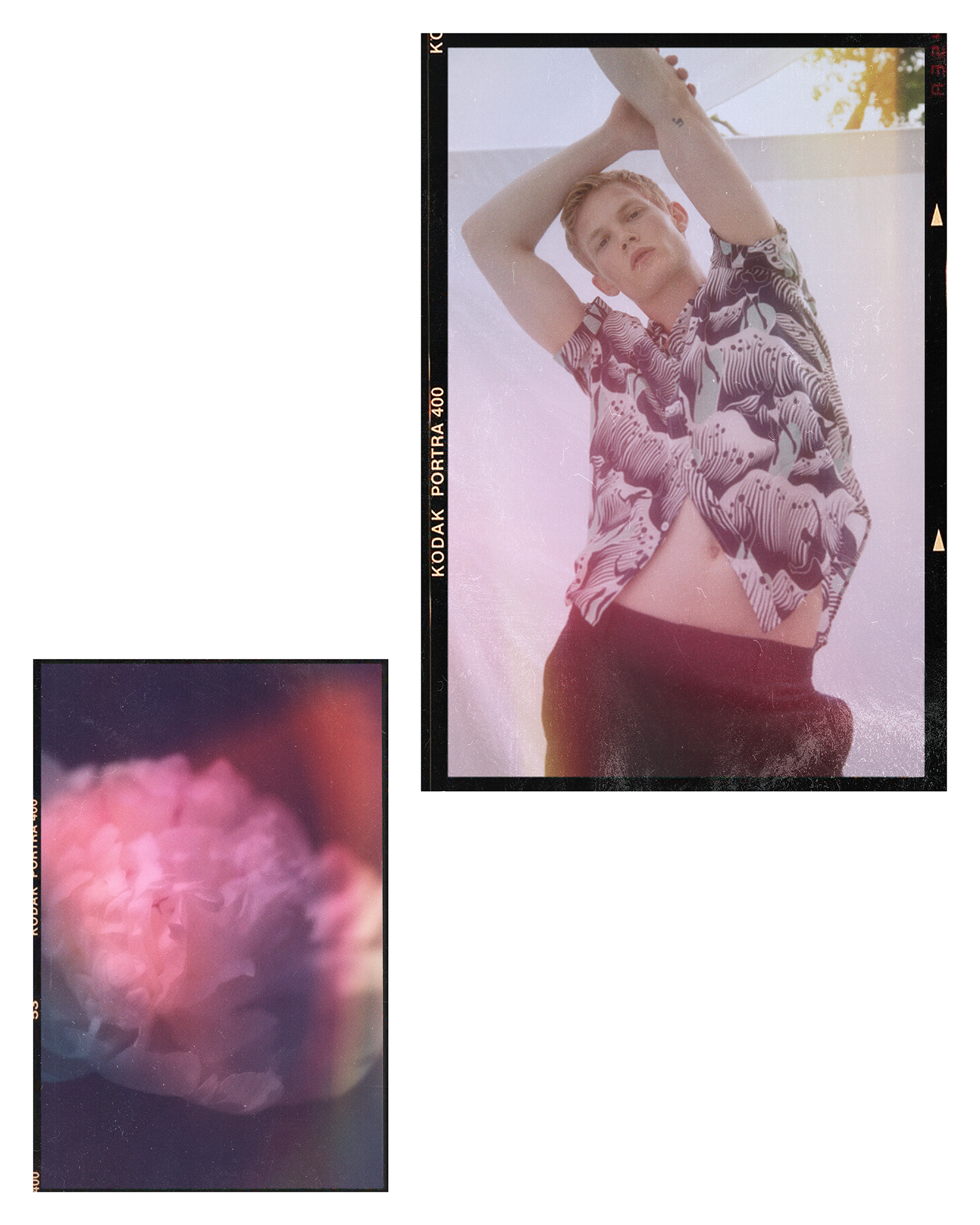

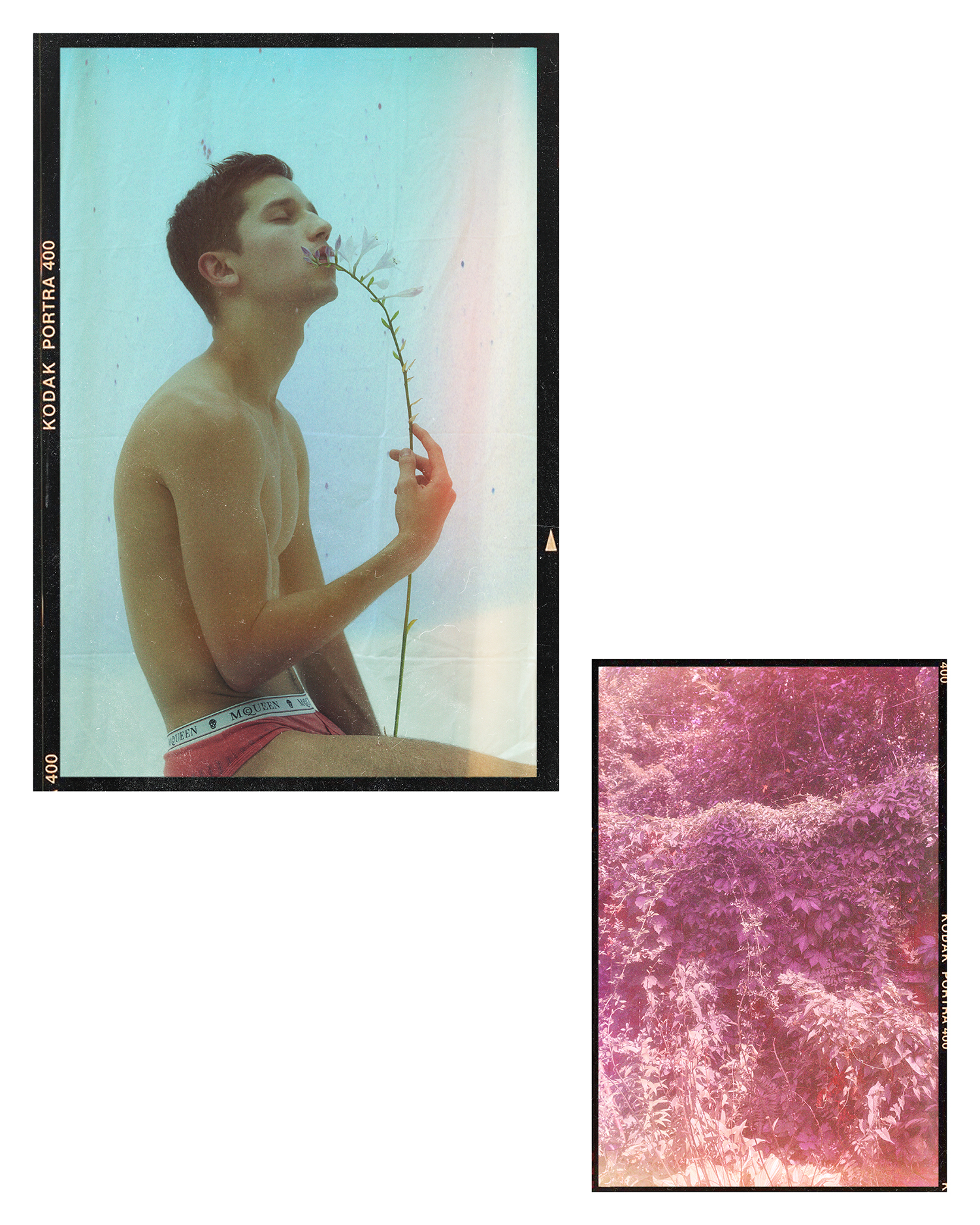

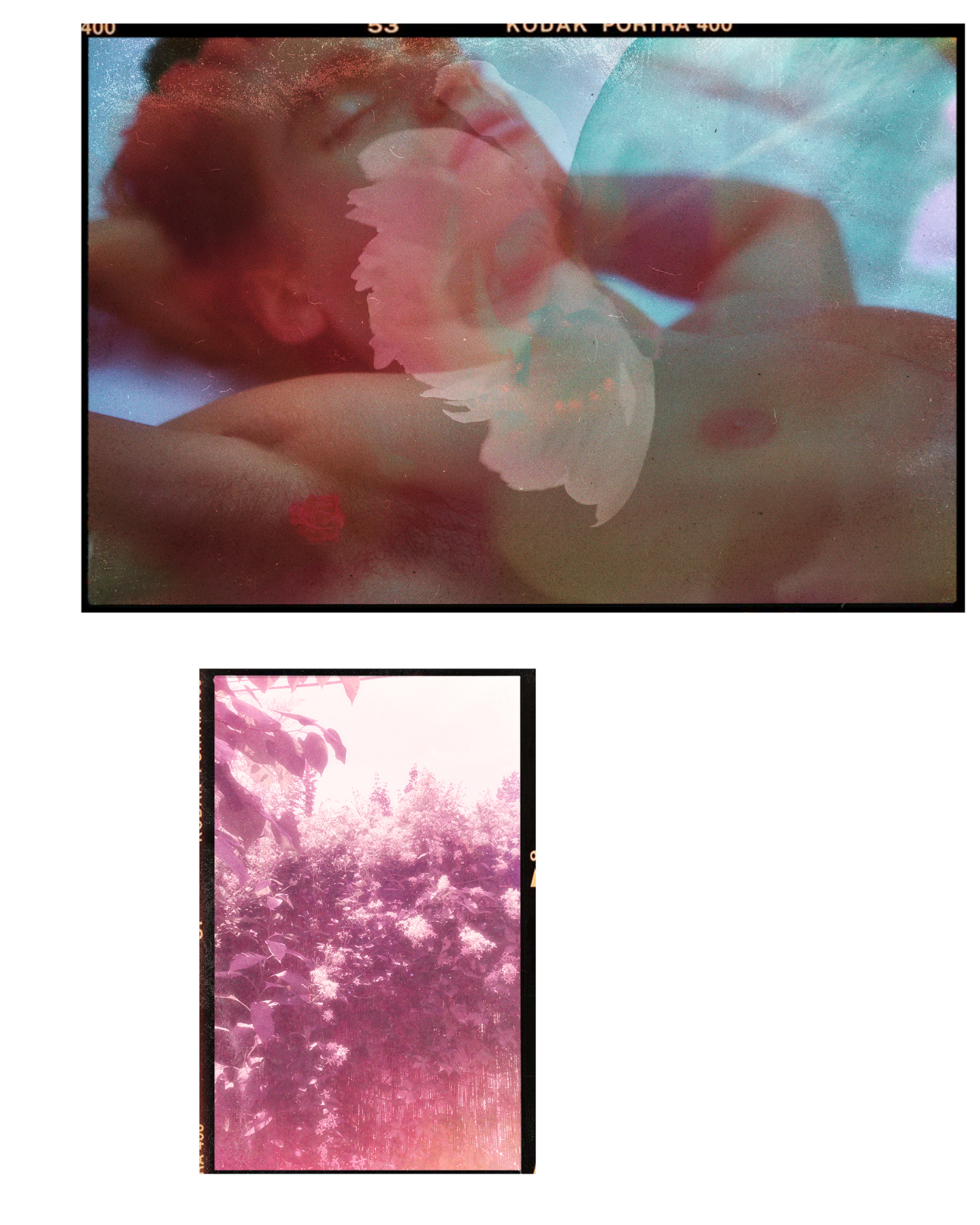

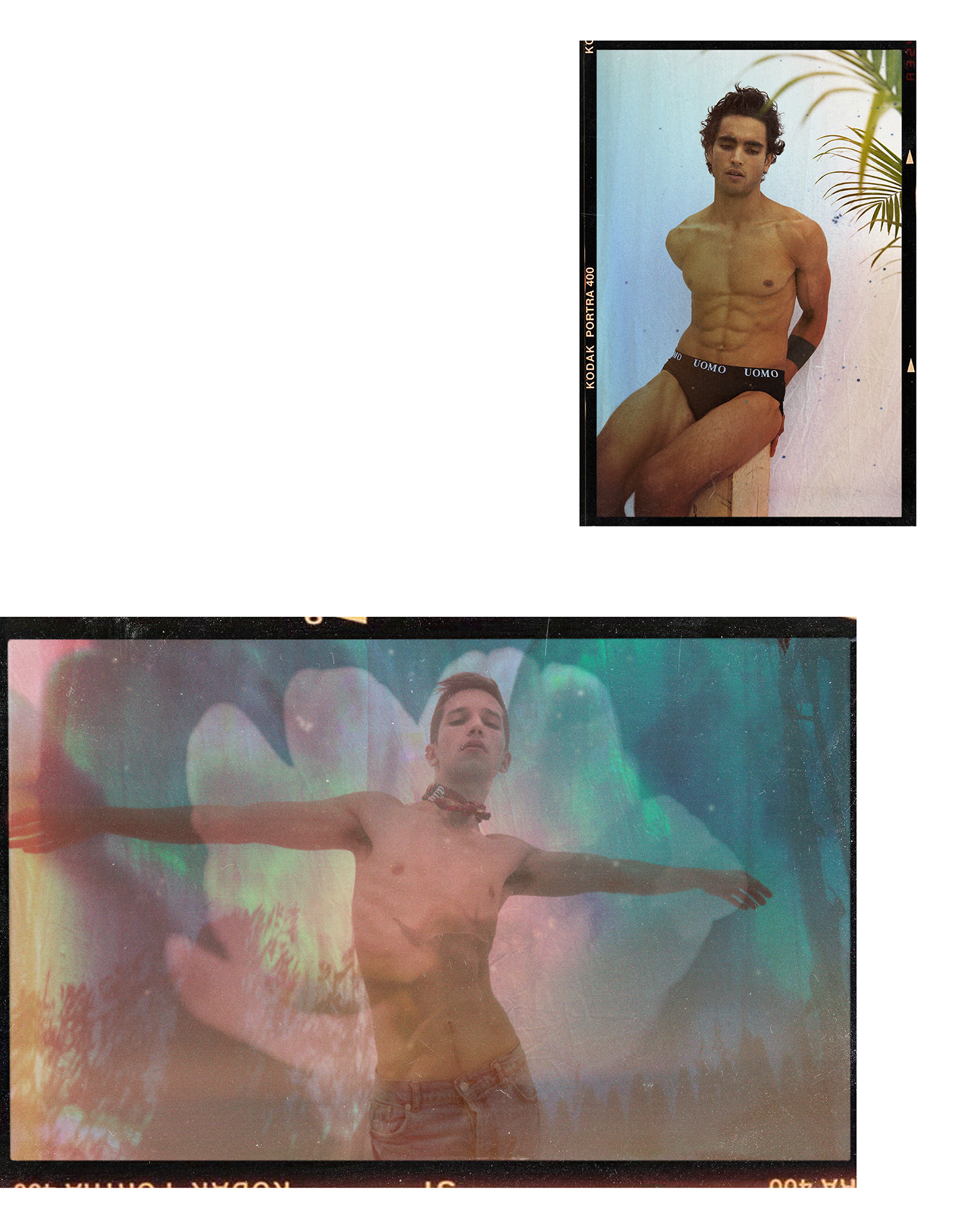

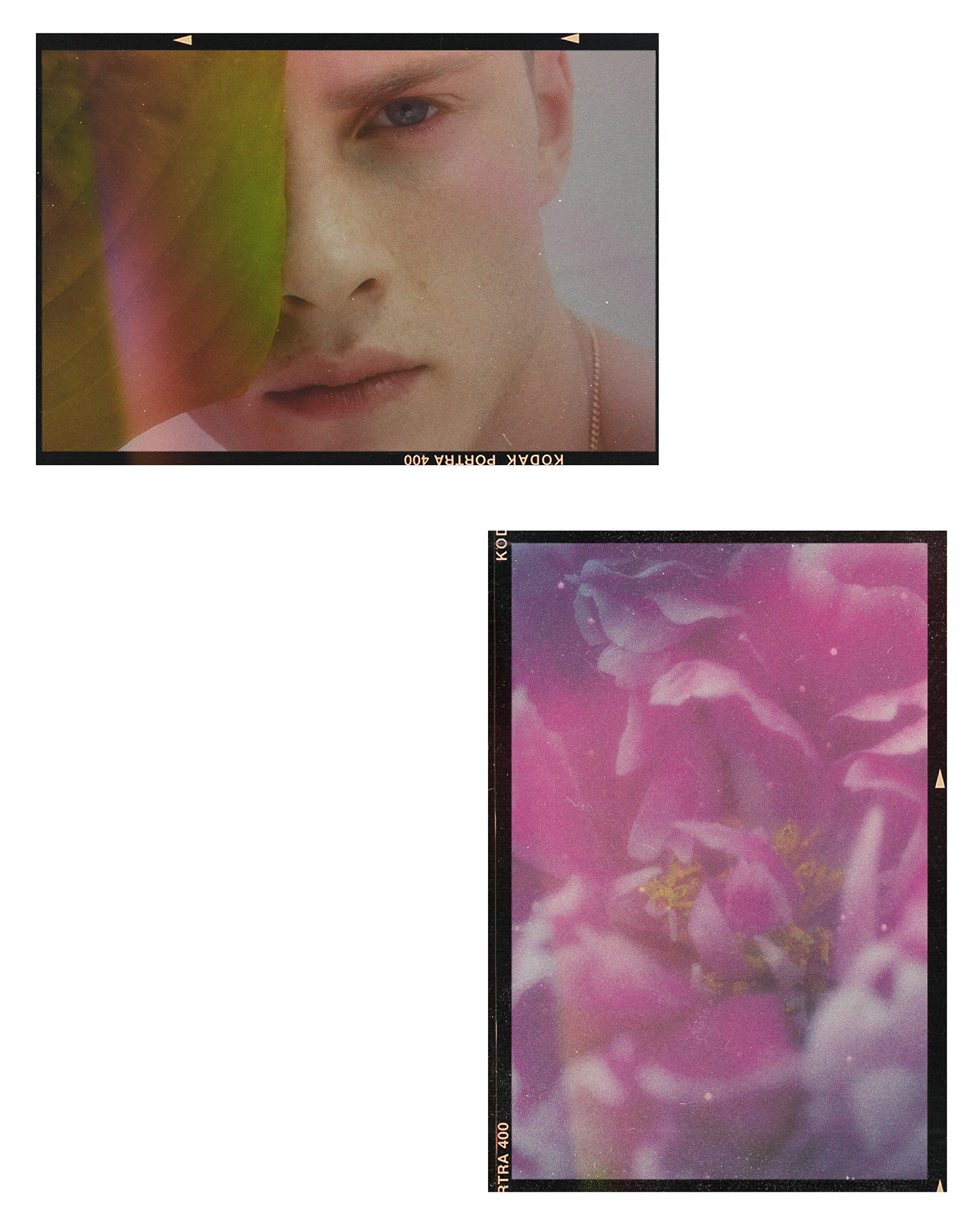

FLOWER BOY

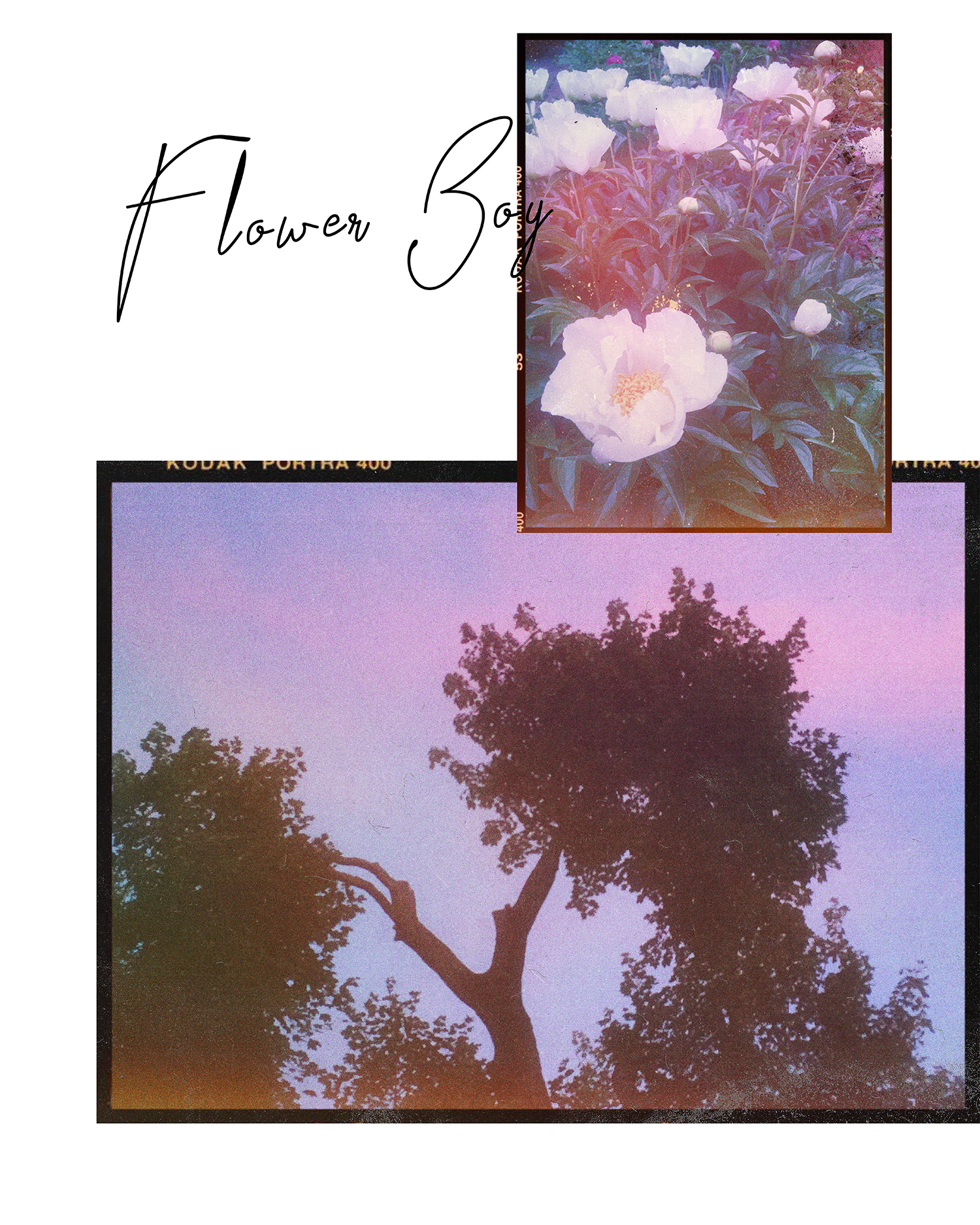

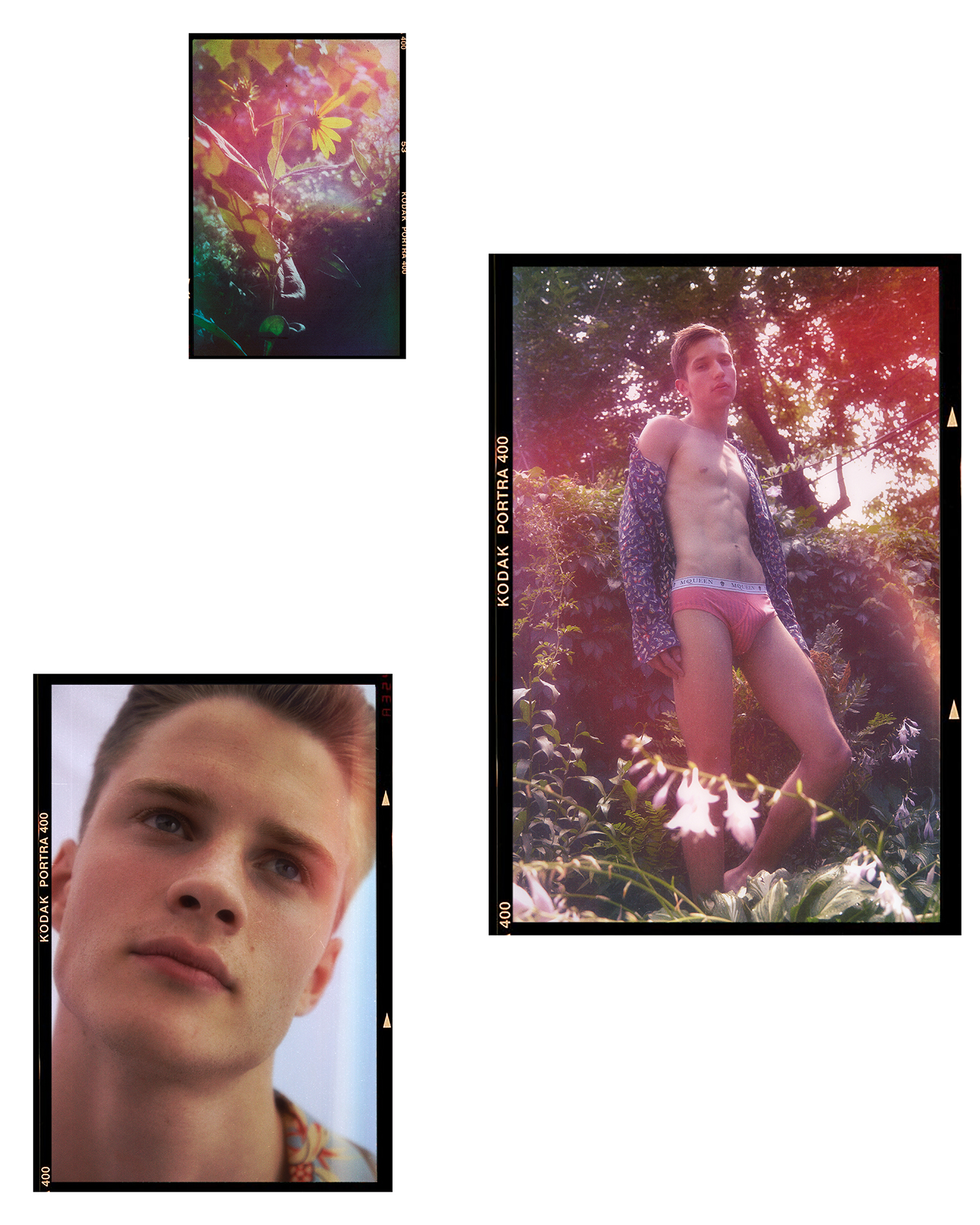

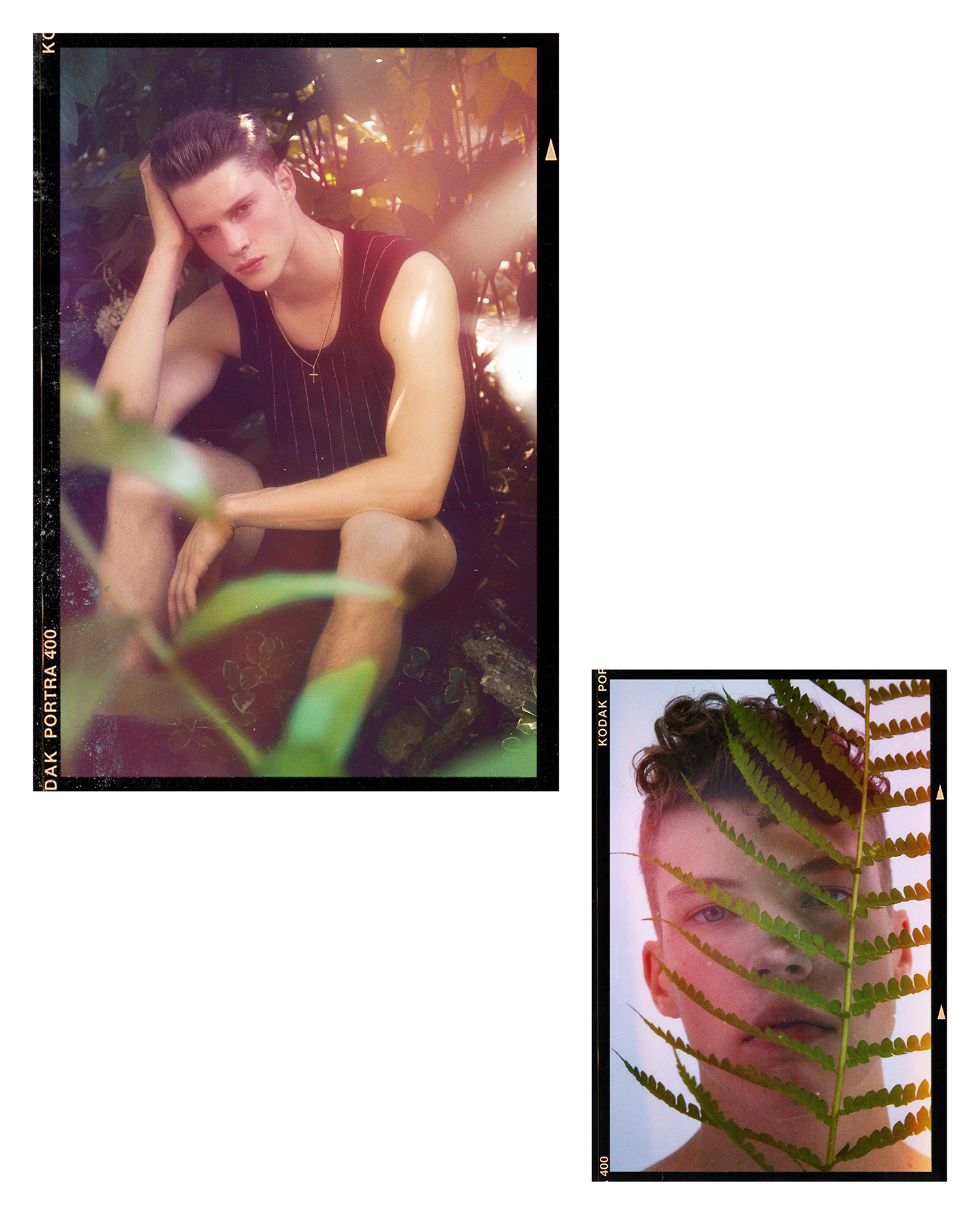

Photographer: Dustin Mansyur

Fashion Director: Marc Sifuentes

Grooming: Anthony Joseph Hernandez

Models: Philipp Proels | Jesse Gwin | Alijah Harrison | Eliseu Zimmer | William Schultz | Logan Booneof

A diverse glimpse into the worlds and personalities of fashion, beauty, culture, philanthropy, and art.

Photographer: Dustin Mansyur

Fashion Director: Marc Sifuentes

Grooming: Anthony Joseph Hernandez

Models: Philipp Proels | Jesse Gwin | Alijah Harrison | Eliseu Zimmer | William Schultz | Logan Booneof

Head piece by Harlem’s Heaven | Dress by Laurence and Chico

Photographer: Anastasia Garcia | Model: Awar Mou @ RED Agency | Stylist: Tiffani Williams | Hair: Kristi Wilczopolski @ Bryan Bantry Agency | Makeup: Julianna Grogan @ Bryan Bantry Agency | Photo Asst: Brandon Harrison | Photo Intern: Nina Dietz

Dress by Alena Akhmadullina

Dress by Alena Akhmadullina

Head piece by Harlem’s Heaven | Dress by John Paul Ataker | Gloves by Wing and Weft

Head piece by Harlem’s Heaven | Dress by John Paul Ataker

Head piece by Harlem’s Heaven | Dress by Maison D Ferrer

Head piece by Harlem’s Heaven | Dress by Maison D Ferrer

Dress by Laurence and Chico | Jewelry by Tuleste

Dress by Alejandro Collections | Gloves by Wing and Weft

Dress by Alejandro Collections | Gloves by Wing and Weft

Photography by EVGENY MÍLKOVICH

Singer Kim Petras stunning in platinum, slicked back hair and silver leather.

Elaine Welteroth, journalist and former editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue, in an all-white moment.

The godfather of Harlem style and current Gucci collaborator, Dapper Dan arrives at a show.

Christina Aguilera in blood red leather.

The cutest dog ever. omg.

New York nightlife personality Kyle Farmery merges day and night.

Famed stylist and designer Patricia Field smiling on the way to the next show.

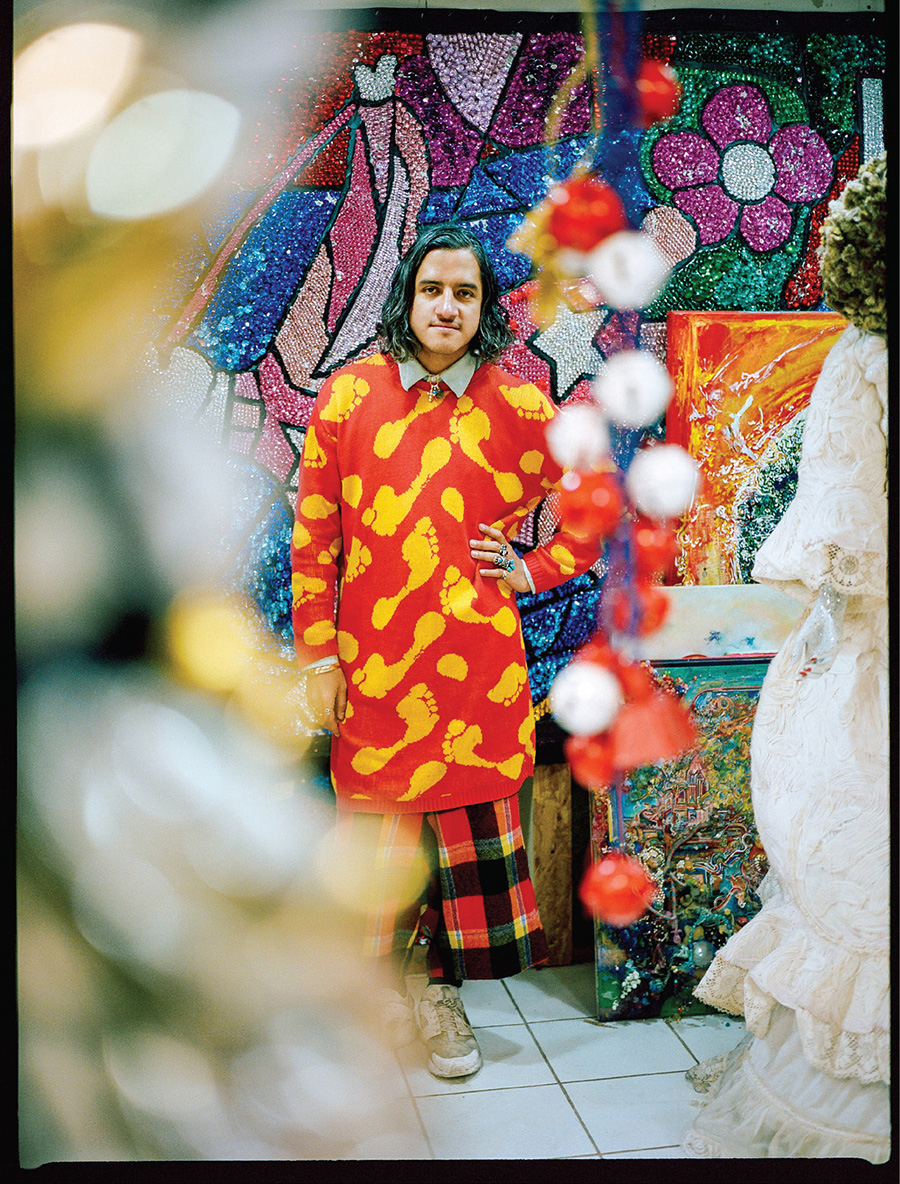

Among a menagerie of rainbow-hued, glittering, plastic beaded life-sized figures, standing like a proud father overlooking his artistic creations, the charmingly unique Raúl de Nieves shares his artistic rituals with us in his cathedral of creations.

Photography by Tiffany Nicholson | Interview by Mariana Valdes Debes

Blending the lines between the human and the artificial, Raúl de Nieves’ instantly recognizable shoes, masks, and humanoid figures are at once fantastical, desirous art pieces, yet remain relatable and human. Located in the heart of Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, de Nieves has created a studio filled with beads, fringe, ephemera, and anthropomorphized beings who appear to dance and interact with each other.and it is within that studio where we met the artist and sat down to discuss his art and unique perspective.

Born in Michoacan, Mexico, immigrating to the United States at the age of nine to California, and following the winding path to New York City, Raúl has made a name for himself and cut a swatch of color through the country. In our current state of political turmoil, climate change, and war, it is a breath of fresh air to see the talent that emanates from each piece of art that de Nieves creates as well as from the artist himself.

Here, Mariana Valdes Debes, an international art promoter of Mexican artists, sits in conversation with Raúl for Iris Covet Book.

Hello Raúl!

Hi Mariana, it’s nice to talk to you.

Nice to talk to you as well, I think your work is amazing! I want to start from the beginning and ask how growing up in Michoacan, Mexico influenced your decision to enter into the world of art?

Growing up in Mexico, especially in Michoacan, was really enriching through the different cultures, craftsmen, and artisans. My family was always really pushing for us to see what Mexico had to offer. I remember seeing artisans working in their community, and I came to the United States with that knowledge and those memories. I’m not trying to emulate what I saw, but I am creating these narratives through performances and storytelling, painting, installation, and at the end it’s about creating experiences for yourself and for others to be part of.

Your exhibition last summer “El Rio” was an analysis of the western cultural view of death and the antithetical idea of death as an “ecstatic mystery of life” – how did that concept come to fruition?

I’ve experienced a lot of death in my family, with my friends, and it’s something that we all have to face at one point. My father passed away when I was very young, and it helped me understand that it’s a part of life. Obviously we mourn when someone passes away, but how do we continue to celebrate their lives and what does that mean? To understand that they are not physically here, but emotionally they are closer to me now than ever. Having a really close family member pass away is one of the scariest things, yet it’s also like becoming closer to that person. It’s something that I had to experience and move past.

The majority of your body of work is comprised of fantastical humanoid creatures made of glued beads and other miscellaneous non-traditional material— how did the decision of using these materials come about?

The bead has been utilized by many cultures, but somehow we forget that it’s this beautiful little piece of material that can transform in so many different ways. I went to New Orleans during Mardi Gras and came back with a suitcase full of beads. From then on it just made a lot of sense. All of a sudden they just started to appear more and more in my life.

Well the beaded shoes you created in your earlier work are really just to die for. Every time I see them I just wonder what it feels like to wear them.

They are actually really uncomfortable. I think that’s the best part about it—they are beautiful objects of desire, but when you actually put them on they hurt. When I wear these objects in my performances, it becomes part of this struggle to portray myself as this specific character. I don’t know, it’s kind of magical. Sometimes we want these beautiful objects, but they are obviously not the most practical things we should long for, but we still do.

In an interview with MoMA, you stated that one sculpture, Day(Ves) of Wonder, took you seven years to complete but you never gave up on it. How does the process of creating each labor-intensive sculpture strengthen or teach you as an artist, and do you think that the number of years changed the idea behind the piece over time?

The work is made completely of beads and was a very complicated piece to build. I started to make these huge sculptures and was fantasizing about what it would be like to create a full, life-size figure out of beads. It took me so long because there was a lot of trial and error. The piece spoke back to me and taught me that every time I felt like I was failing, there was a possibility that it could continue to work as long as I had the ability to go forward. Till this day, it’s one of my favorite works. Day(Ves) of Wonder derives from my mom’s daycare called “Days of Wonder”, and I was thinking how interesting it is for my mom to have these small periods of time with these kids as they grow up. I think this piece had this same idea of learning from each experience. I don’t know when I’ll have another moment to work on something for that long, or if I need to, but it really gave me so much understanding to know that every time I went back and started working on the piece, it was teaching me something in return. Maybe that’s why that piece is so celebrated, because people feel that energy within its expression and within its movement.

You never gave up and you went through stages creating the piece, becoming a master of the process.

Yeah, exactly! There’s beauty in creating this object that doesn’t have a moving life or a soul. Through our emotions and the experiences that we project into these objects, the energy that resonates with the viewer creates the idea of a life behind it. To me, the sculpture is of a seven year-old child because of the time that I spent with it and how I saw myself growing. It was an ambitious task to take on and I don’t want to reproduce another one because this piece lives on to be a celebration of an experience and a time. I still question what that piece actually continues to mean to me. That’s the beauty of art, you can work on something forever. As humans we’re constantly doing that; we’re always working on who we are and trying to figure out what it means to be human.

That brings me to my other question. Surrounded by these figures every day, do they develop personalities and life stories of their own as you become attached to them?

Yeah, of course! It’s amazing to build each piece with its own identity, and this identity can be processed through the relationship of the other works next to one another. I like to believe that we live in a fantasy world and we should give ourselves some freedom; life doesn’t necessarily always have to be so concrete. As children, we get this beautiful time of our life to dream and imagine, and then we get to a certain age and give up on that. I constantly imagine myself to be this fantastical person, even if it’s just for a moment.

The performance aspect of my work allows me to tap into these roles that I can’t necessarily inhabit on an everyday basis. It’s a great gift to be able to perform these silly experiences or cathartic moments through these characters, and there’s comfort in putting on a mask and allowing yourself to not really be seen as human, but to be something fantastical. Having this ability to tap out is really cool and I think that’s why a lot of cultures use costumes and perform these beautiful dances, plays, and fables to tap out.

I want to ask about your use of vibrant colors. How did your very maximal use of colors develop over time?

Colors can create very emotional experiences, and I guess that’s why I tend to use so many bright hues of colors. I’m trying to learn how to really control what the color can do, what it means, and what it can put out into the world. In a way, color is like language, it allows for people to feel a certain way. The simplicity of these tools that we already have and putting them into artwork is not necessarily about following rules but following common sense and what feels natural.

Like just going toward the aesthetic of it, the feeling and the emotion that comes through the first time.

Yeah, for awhile my least favorite color was red, so for a year I only wore red to understand why. I had so many different experiences with strangers asking me why I was wearing all red. People would come up to me and try to tell me what they felt red meant to them. It was really interesting to do this exercise for a year, but I’ll probably never do it again.

Well that must have felt like a performance. Yeah, exactly. I wasn’t really intentionally trying to make it a performance, but it was a very interesting exercise. As a Mexican-American artist, how do you feel about the political climate in both countries? Do the current political events inspire or influence your work?

The current President having these views towards Mexico is very archaic. But I realize it’s been happening since the beginning of time, as hard as it is to believe. I try not to be too political about it, because I know it’s not just the United States versus Mexico; it’s the world against one another. When will it end? Who knows? You would think by now we could unite and make this place even better than it is. We are made of the same matter; we need to understand that we will be stronger together. The idea of immigration is beautiful. It has allowed me to believe in acceptance for all. It is beautiful to know that you can somehow be who you are and be accepted and be part of a new nation. That idea has influenced a lot of my work. Everyone has a different experience with immigrating, and in the end I am thankful that I was accepted into a new culture, and that maybe I can influence more people to believe that this is a positive possibility.

A quick scroll through your Instagram reveals an interest in religion and historical references. Where does this interest come from?

Well, I’m a spiritual person. I have a lot of faith, and not just in history or the idea of religion. I like feeling that there is a higher power, or that perhaps believing is what creates a higher power. For me, spirituality is a way of life and it helps to ground myself and cope with all of these catastrophes happening around us.

What do you view as your biggest personal accomplishment to date and why?

Self-acceptance. I’ve been able to really accept myself, and not just myself, but also the people around me. In a way, that’s a huge accomplishment. I think it’s self-love and acceptance that’s made me as open as I am, and as a result I can be my true self.

What can we expect next from you?

I’d like to make art more accessible, to create more experiences that can be accessible not just inside the art world, but also outside. I don’t know whether that means creating public artworks, or if that even changes anything, but I just want to really feel like there is more openness to everything.

And in 10 years?

In 10 years? Maybe I’ll have a dog.