TRACEY EMIN

Once called the “enfant terrible” of the Young British Artists, Tracey Emin’s confessional, autobiographical work fearlessly intimates that the artist is here to stay.

Portrait and Studio Photography by Oli Kearon | Interview by Sarah Nicole Prickett

––

In a beautiful new compendium entitled TRACEY EMIN: WORKS 2007-2017 by: Jonathan Jones, published by Rizzoli International Publications, we can view a decade’s worth of work of the prolific and inimitable Tracey Emin. Compiled in close collaboration with the artist and unprecedented in its scope, this definitive book collects ten years of Tracey Emin’s drawings, paintings, sculptures, appliques and embroideries, neons, video stills, and installations. A multimedia artist whose intensely personal work blurs the boundaries between art and life, Emin remains one of the most highly publicized contemporary British artists and continues to stir as much controversy as she has acclaim. A multimedia artist whose intensely personal work blurs the boundaries between art and life, Emin remains one of the most highly publicized contemporary British artists and continues to stir as much controversy as she has acclaim.

Moving chronologically through a prolific decade of work–from major public installations to recent reflective paintings and sculptures–this book shows a coherent vision that defies the idiosyncrasies of Emin’s evolution as an artist. The same mixture of anger, hope, curiosity, and vulnerability that informs her delicate drawings and handwritten neon works can be felt in the darker tones of recent monoprints and the weight of later bronze pieces.

Written by Jonathan Jones, whose text places Emin’s work in a broad art-historical context and sees this recent decade of her artwork as an entry point to examining her full career, this is a beautiful monograph on one of the world’s most influential living artists.

––

She is, for enough of us, the first famous, knowable, and wealthy living artist to be a woman. She is the first we could name before we knew quite what art was. Because of this, she has helped decide what we think art is: the outrageous act of doing something because you can, which means that you should. Her sensibilities make crucial sense to the most desirous young artists and writers, mostly young women, but not always. Imitated by dozens, her style has become memetic, which makes it seem more original. It is original as she is. Tracey Emin is permanent.

That’s what she says. The words–here to stay–are stitched in capital letters on one of the blankets she liked to make, in acerbic pastels, from the early 1990s on. This one, titled The Simple Truth, was made in 1994 for the Gramercy Park Hotel Art Fair, where a thirty-year-old Emin slept and showed her work in the same small room and did not feel welcome. I saw it in a book of Emin’s pictures, My Photo Album, which I had not opened since buying it four years ago. Oddly the picture of the blanket took me by surprise. Odd because the ambiguity of “Here to stay,” the provisional, limited idiom of the sojourn turning into a journey’s broad conclusion, is blatantly Emin; and because the early work that is still her most widely known also concerns a bed, namely her bed; and because I had seen pictures of the blankets before and had apparently found this one forgettable. This time its freshness and its near-vulnerability was alarming. I imagined it making people want to cuddle her.

Emin is not generally thought of as an artist whose work keeps one warm at night. The title work in her most recent show, The Memory of Your Touch, is a self-portrait (1997—2016) on another hotel bed, taken from behind as she lies prostrate in red thigh-high stockings. Other works include sculptures, more naked and headless or faceless bodies in jaggy plaster or bronze; paintings that leak cold blood and cloud with the nacreous greys of frozen breath over dysmorphic outlines of the body in chalky blacks; and her signature hand-scrawled pleas in popsicle-pink, slinky tubes of light. Her idols are dead, untouchable, macho like Rodin and Schiele, and we see their relentless impressions on her figures. In her “neons” she is most obviously, saleably herself, and these have become fixtures in expansive hotel lobbies from London to Miami, New York to Istanbul. Most spell out more of her words: You Should Have Loved Me. I Followed You to the Sun. I Dream of Sleep. One, at a hotel in Oslo, traces a humanoid figure, bloated with withering limbs, made and titled in homage to Emin’s favorite painting: Munch’s The Scream. It seems made to induce the nightmare of your life.

Good Red Love, 2014 © Tracey Emin. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy: White Cube

Hers is like a Cinderella story stuck at a minute to twelve. Born like Kate Moss, in Croydon, South London, Emin spent her childhood in the rough-edged seaside town of Margate, where her mother ran a hotel her father owned. At thirteen she was, as she told us in her lacerating memoir, Strangeland, raped in an alley behind a tavern. At twenty-seven she had her first abortion, carrying the killed fetus home in the back of a taxi. Nearing thirty, with a degree from the Royal Academy in London but practically nothing to her name, she burned all the fine little lithographs she used to sign “Miss T.K. Emin” and started over as Tracey qua Tracey. She made five-minute films that looked like very unfunny home videos, like the one titled Why I Never Became a Dancer, which loops through her thwarted adolescence as images of Margate unspool: “The reason why these men wanted to fuck me, a girl of 14, was because they weren’t men. They were less. Less than human. They were pathetic.” It was 1993.

Sick, delicious egoism, paired with ironies that were a bit rich, was all the rage in Emin’s milieu, which included Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst, and Anya Gallacio (it was in Artforum’s 1992 cover story on Gallacio that Michael Corris coined the term YBAs, for Young British Artists). Emin and Lucas opened a shop in Brick Lane, painted the walls pink instead of white, and sold t-shirts with “slogans” like Have you wanked me yet? Emin titled her first solo show, facetiously but not self-deprecatingly, My Major Retrospective (1993). Corris called her Sandra Bernhard and Beuys in one body. “Emin’s persona,” he said with emphasis, “is designed to look as though it can take everything life can throw at her.” Messiness, of course, accommodates more mess. When the mess becomes massive it looks like a cover-up, where the crime is ambition; and it’s hard to be sure that ambition is not per se criminal. Only, it’s apparent that when a woman reaches success before losing her sex appeal, her talents are perceived to be strategic, not divine. Emin’s rise inspired some of the art world’s hottest debates over craft, narcissism, and intent. Enviable, she could not be beloved.

In the six years between her “retrospective” and her first (and last) nomination, with My Bed (1999), for the Turner Prize, Emin made a brand out of getting blackout drunk and saying unbelievable things in the press. When she claimed, like she did after one particularly wild televised incident in 1997, to not even remember she’d been on television, the press insinuated she not only remembered but intended doing it–anything for a headline, as if she were both headless and single-minded, or strategically mental. The persona stuck to her work. Colm Toíbín, in a review for British Esquire of Emin’s 20 Years retrospective, about summed it up, saying, “her drawings have a starkness and an aura of desperate loneliness attached to them. Her nudes are drawn with merciless care; they manage to achieve an effect which is spare and plaintive.” He notes the effort in making My Bed “so unglamorous, all tossed, with knickers stained with menstrual blood, among other things, on the floor beside it, the last place you would lie down to rest.”

Emin has been soberish, meaning she drinks wine but not spirits, for eighteen years, and it is no longer her fault that she forgets things. She tries to remember. She is trying to be remembered–as what? Enormous. Great. A vast power. Her work becomes vaguer and vaguer, even as it solidifies and gains mass. Primal scenes dissipate into other people’s myths, words blow up and fuzz into lyricism. Something was lost when she shed the itchy habit of the first-person, shameful confession, when she stopped calling her pieces my that and my this and started saying your, yours, you. It became unclear what she loved. Something, some meaning. I cannot remember either what the meaning is.

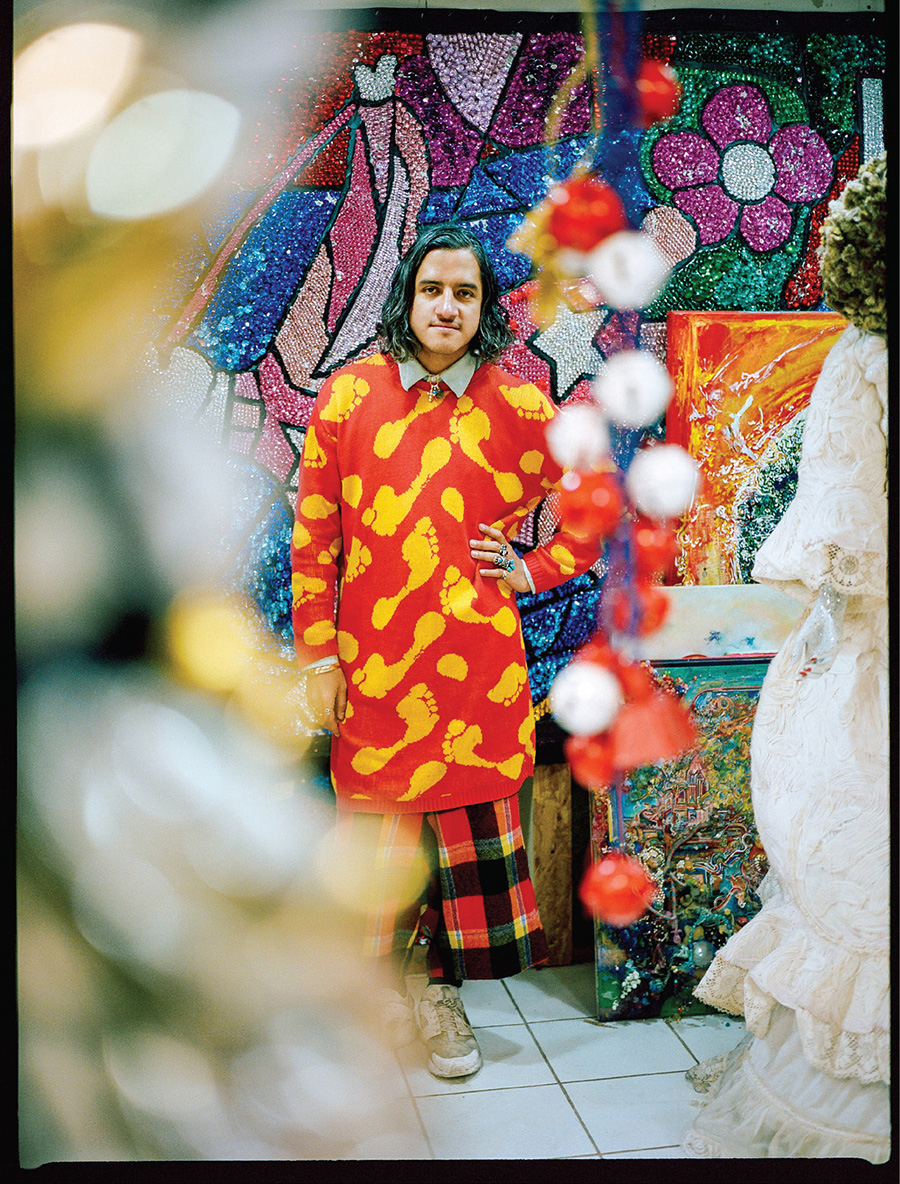

Studio Photography by Oli Kearon

Studio Photography by Oli Kearon

My lips moved across your face, 2015 © Tracey Emin. Photo: HV-studio, Brussels. Courtesy Xavier Hufkens

I call Tracey Emin at her studio after lunch, her time. There is the just-caught breath. There is the click of a lighter. Her voice, never mind all the cigarettes, retains the softness of Egyptian cotton. It’s possible, somehow, to hear the ‘e’ in Tracey, the barest flutter of vowel.

She gives a sigh of displeasure at telling me what her days are like, or how they are not alike. Last week she was in Paris, Brussels, Rome. Today she and her team are renovating Emin’s studio, which is over eight thousand feet of former factory space in Spitalfields, East London, with a swimming pool in the basement so she can do laps in the space of a smoke break. Next year the operations will relocate a new, larger space in Margate, where she can swim in the sea. London is “too noisy,” says Emin, “and too full of shopping.” She will wait until night to make, say, the molds for her sculptures, working from one o’clock in the morning until three o’clock, seven o’clock, eight. Then the emails start: “I don’t even know how many emails I get, too many to count, every day. One demand after another. And all these questions.”

Emin has a propensity to feel questioned. She listens badly and is quicker to hate a question than to hear it, perhaps because she assumes her interlocutors think the worst. When I say that she got famous by not sleeping, by seeming to party all night while actually staying up to work, what she hears is the accusation echoed: “I was working then and I’m working now. I don’t like to go out. I never did.” When I ask whether her works begin with shapes or notions or, perhaps, with their titles, which are memorable and seem so definitive, she says: “No, you’re wrong.” Then she considers. “The title is the subject,” she says. “The title or the subject is a loose net that catches things, and whatever fits inside the net stays, if that’s not too pretentious.” Emin has never seemed pretentious. Her most-used words, in conversation, are different forms of work. “All the wildness is in the work,” she says. And, “there is a calmness in me when I am working.” And, “the work is working toward the crescendo of the subject.” When she says that the subject is often a question, it becomes tempting, though unwise, to ask a question containing the word tautological.

Yet Emin must delight in being questionable. A few hours after she hangs up the phone, she says, she will be going out, but only to dinner, and only then to see her friend Mike Bloomberg. Bloomberg, the billionaire exmayor of New York, is Emin’s idea of a man who should be leading the free world. She asks, when I express my doubts, whether I prefer having Trump. She says that my not voting in the election was smart, even if it wasn’t a choice but a consequence of being Canadian. She thinks Mark Carney, a Canadian economist who currently serves as Governor of the Bank of England, would make another good President of the United States. There seems to be no useful reply. It occurs to me that Tracey Emin is a Conservative. It occurs to me, in particular, that I once read a story in the Telegraph saying that Tracey Emin feels abused by other artists for voting Tory. “Anyway,” says Emin, “I am going to dinner tonight as a representative of–of myself, not as myself, but as a famous international woman artist.”

Studio Photography by Oli Kearon

Studio Photography by Oli Kearon

When the artist was younger, she did not think of representation, or of being represented. She did not go around calling herself a feminist, and whether she was one is irrelevant to the fact that, as Emin herself has said, she experienced sexism at the hands of institutions and critics. But then, the word feminist was more a term of art than the marketing term it can be today, and it is today that the term sticks more easily to work signed “Tracey Emin.” She is aware that female artists who are younger, prettier, and better off than she was at the start of her career are prone to copping her style: Petra Collins, the photographer, artist, and model who was born in Toronto the year Emin showed her first piece in London, has done a number of pieces spelling out Rihanna lyrics and late-night iMessages in Barbie-pink neons. Emin-lite, I might call it. Emin doesn’t mind. She is not, as a woman, threatened by girl power.

“I don’t mind being imitated when the artist who’s doing it is really young,” she says, not naming names. “It’s natural for young artists to pay homage and even to copy. What annoys me is when people my age who are just copying and trying to make a name off my ideas.” Emin is possessed of a congenital, gentle smirk, which often appears in flash photographs to be something meaner, or darker, like a scowl. It is easy to picture her scowling now. “Number one,” she continues italically, “they’re not going to heaven. Number two, they’re not even artists, they’re a sort of designer. And number three, how can they get any satisfaction out of it? They can’t.”

Emin believes that art is not a task but a vocation. She utters the phrase “doing what you love” as if it’s never been said. She says, as she has said in most recent interviews, that her work is getting better as she ages. Better how? “Stronger.” How does she know? “Because of the pleasure and understanding I find in it.” Have there been any changes to elicit new strength, or understanding? “No, I am the same person.” A breath. Then: “My mother died last year, which changed a lot about how I feel, how I am in the world.” What was the biggest change? “My mother was alive,” says Emin, “and now she’s not.”

Neon and Mirror/Diabond Installation view: The More Of You The More I Love You, Art Basel Unlimited, Basel, 2016 © Tracey Emin. Photo: Sébastien Bozon. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong, White Cube and Xavier Hufkens

She uses the word “my,” and even the word “me,” more seldomly now. In lieu of a diary, which makes her aware of living posthumously and inspires self-censorship, she writes and sends letters to her friends. “I’m the last person in England using the post office,” says Emin, who also believes, despite what the government says, that “they are starting to take the post boxes away.” In the titles of her recent exhibitions, as in her more private writings, the first-person possessive has given way to direct address: “Love is What You Want,” “You Saved Me,” “I Followed You to the Sun.” She got “The Memory of Your Touch” from a moment in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a husband dead and a widow anguished, missing “the touch of him.” Emin, a desirous reader who’s usually too tired to read, has a different book open at every bedside: a biography of Nabokov, whose author she can’t recall; I Love Dick by Chris Kraus; Provence by Lawrence Durrell. The last book she read cover to cover, almost six months ago, she sighs, was the wonderful novel Horse Crazy by Gary Indiana. She remembers a bit near the end, when a woman artist, suffering from myopia, thinks she sees a cute, brooding guy in a tavern; but when she gets close, he turns out to be a stain on the wall.

Her beds are various, scattered between her studio, her home in London, her other home in the South of France, her old family home in Margate. It’s in France where Emin is “self-sufficient, or somewhat self-sufficient.” She has peppers, tomatoes, and courgettes in her garden, and recently she grew her first pumpkins, though they were “not very good.” There are no good restaurants around, so she cooks. I ask for a recipe. She can’t think of one, and then she doesn’t want to. “I thought we were going to talk about my art,” says Emin. “I am not interested in these questions, and by the sounds of it,” referring to the dilatory sound of my voice, “you aren’t either.” I laugh. She laughs less.

We talk about art, and it is nearly the same conversation. She lists the materials in her studio, starting with the Dionysian bronze she loves for its “machoness.” She makes declarations of increasing dependence on herself. She means a “true” self. She also means a “real” self. “Total isolation, surrounded by nature,” says Emin, “is what I need to really work.” Never lonely in the studio, she continues to feel a longing in bed. Whether the longing is for a man is unclear. Not every you is the you of a very romantic pop song. Quieter, larger, is the you of a prayer.

We talk about her husband Stone, who is literally a stone, a piece of rock, and whom she married last spring in the garden in France where she found him. Stone and Emin “are having a nice relationship,” she says, “although long-distance is always tricky.” It occurs to me that I once read a story in the Telegraph saying that Georgia O’Keeffe left her unfaithful husband for a mountain. “God told me,” said O’Keeffe, “that if I painted it enough I could have it.” Emin, when I tell her this, softly repeats: have it. There is a word loved by the master self-portraitist, and painter of flora and fauna, Albrecht Dürer. The word is Konterfei, which means an exact likeness and signified to him the making of something exactly like. “Yes,” says Emin. “Yes.” She exhales at length. “You asked what I’m working on now. That’s what I’m working on. The thing. The thing that it is. That’s the end of the interview.”

Studio Photography by Oli Kearon