STUDIO VISITS – SAM MCKINNISS

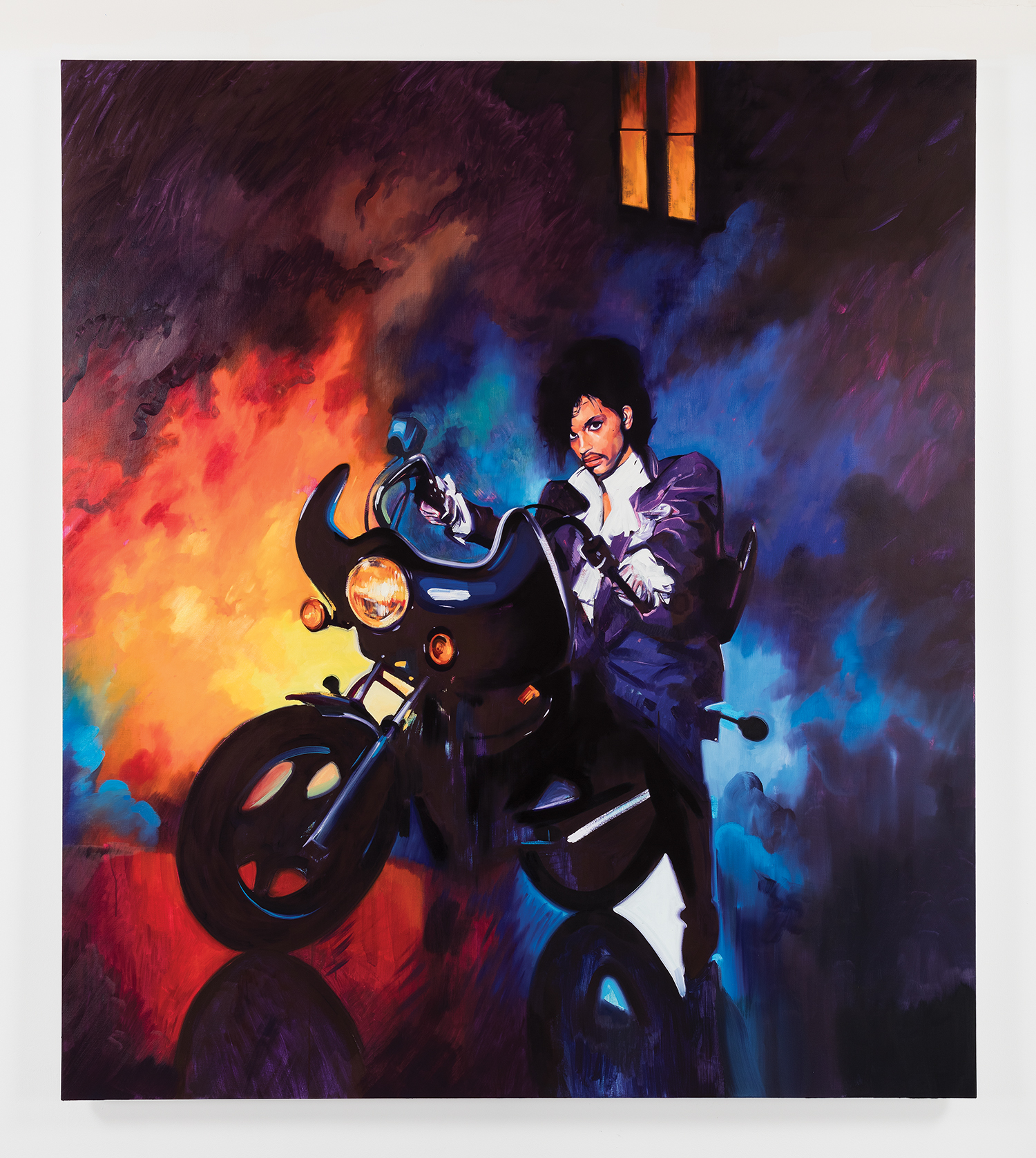

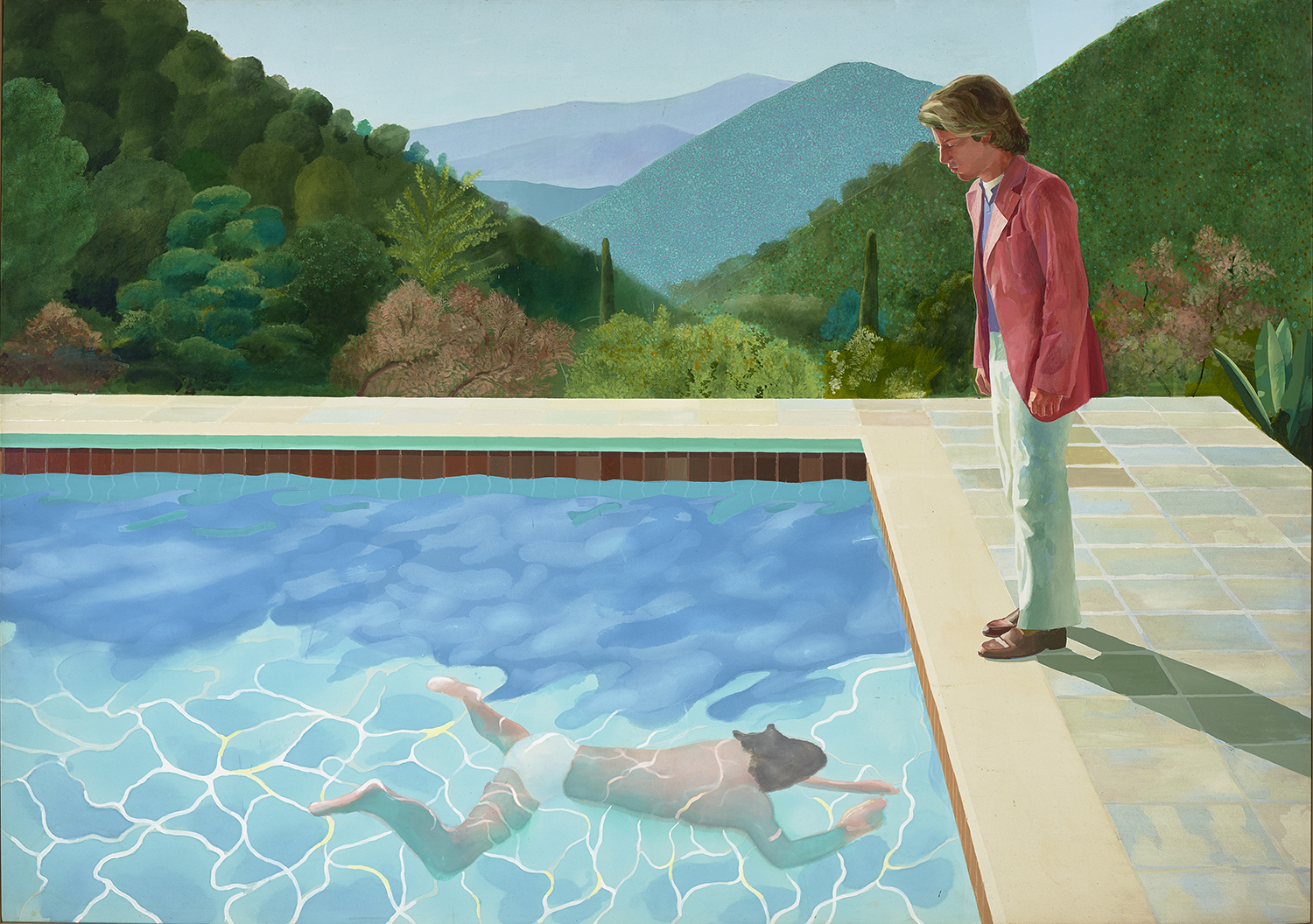

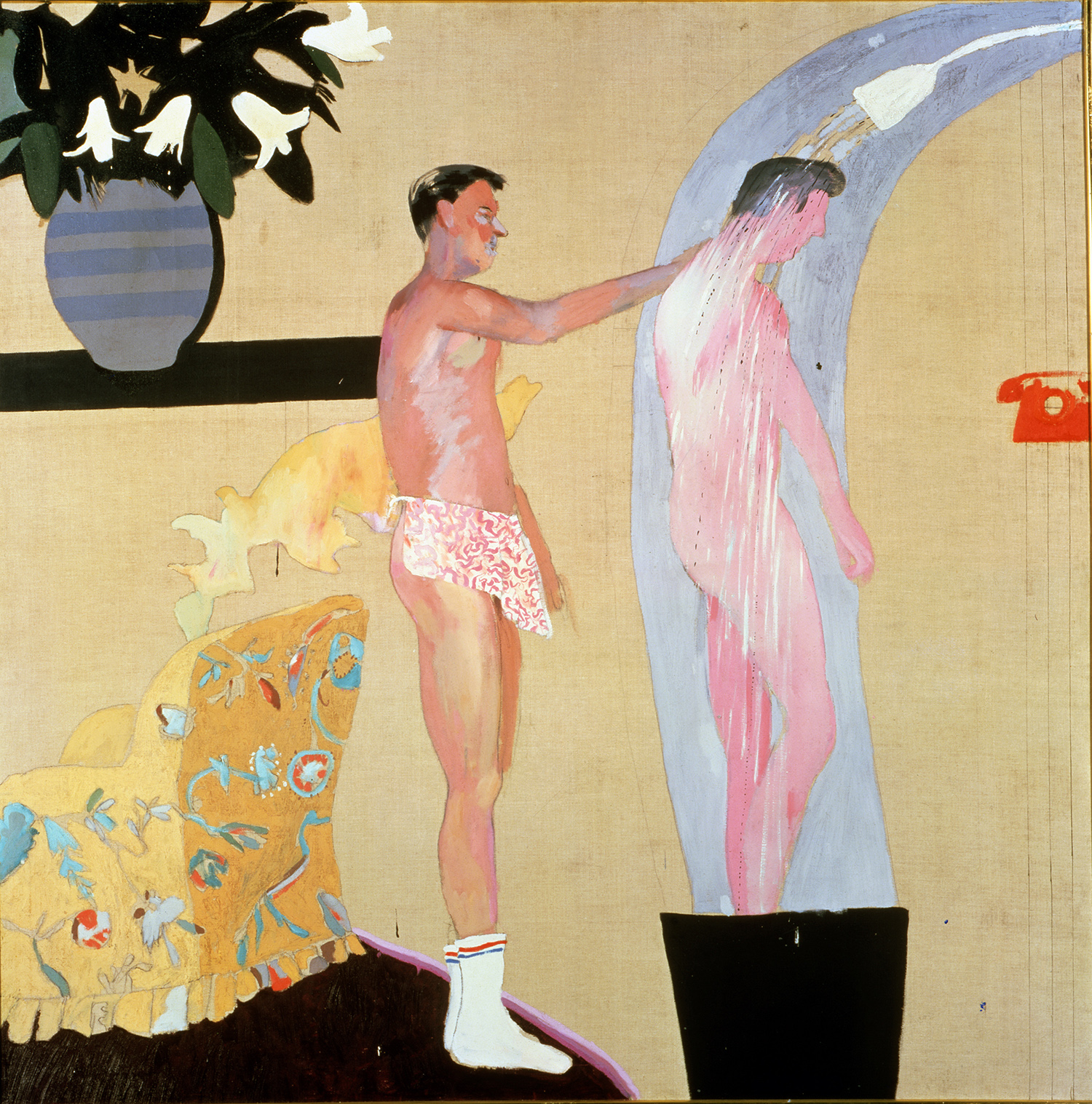

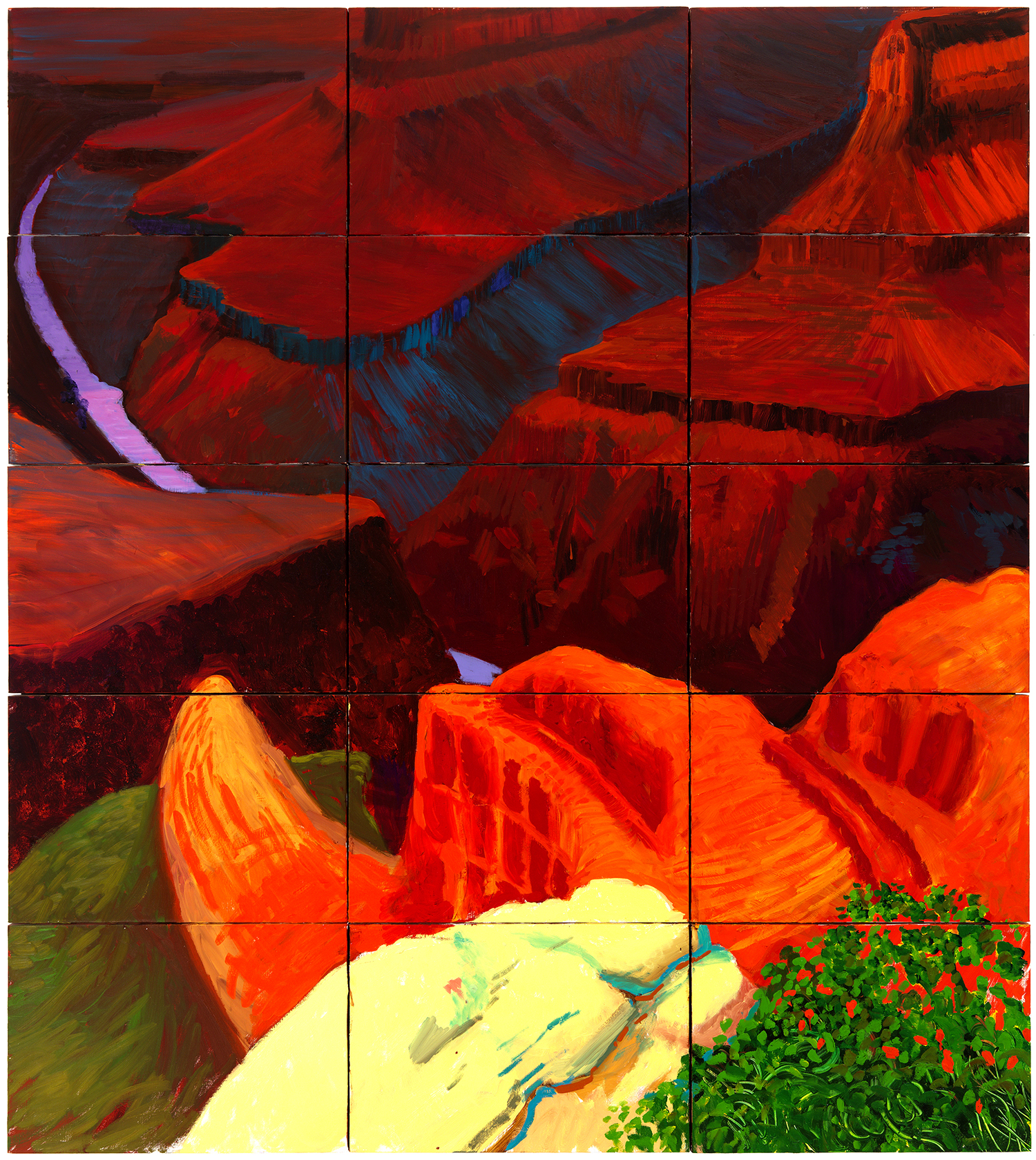

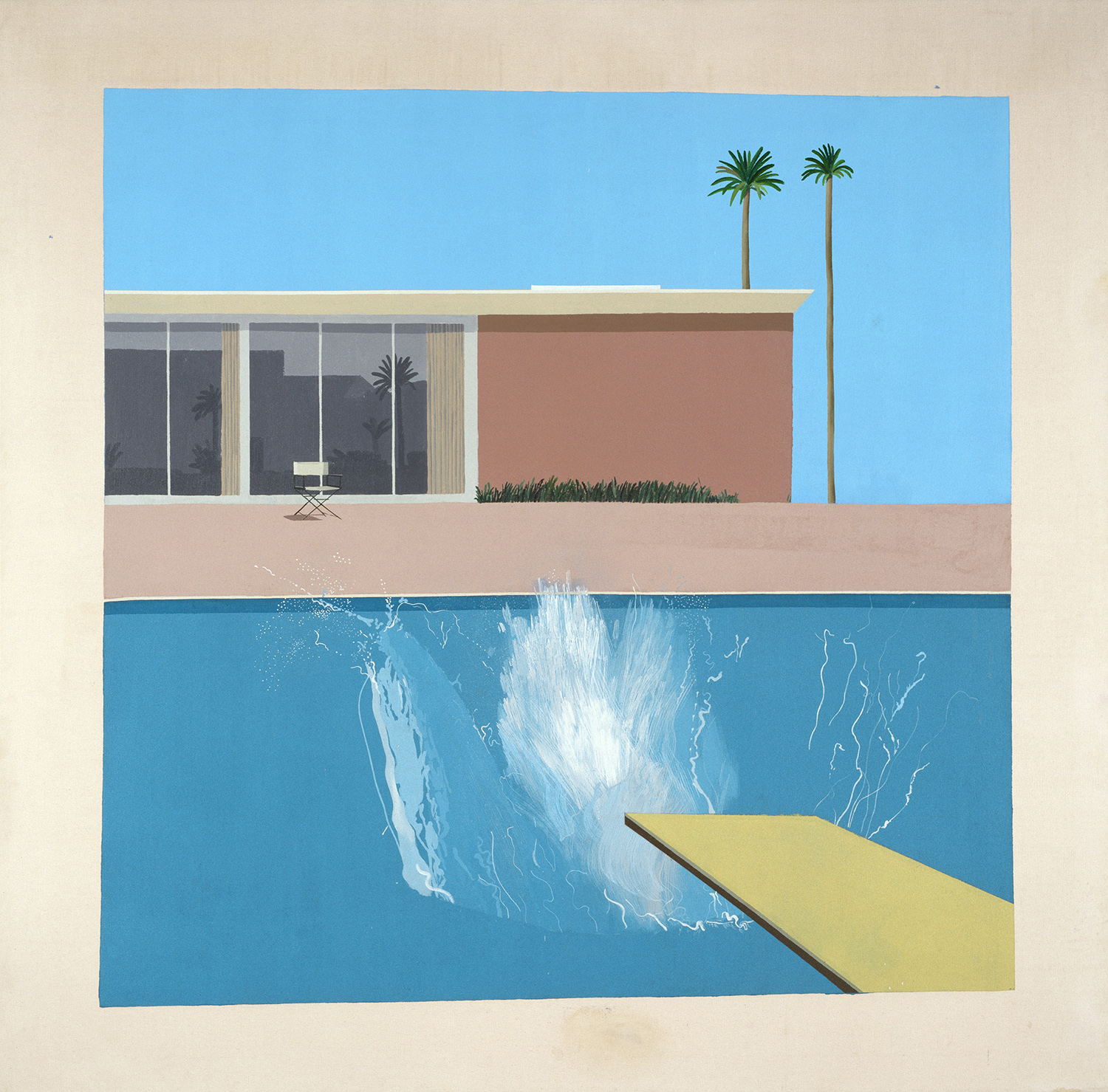

In 2016, Brooklyn-based artist Sam McKinniss made waves in the art world with his sophomore solo show, Egyptian Violet, which featured a memorable, moody portrait of the late musical phenomenon Prince. Known for his signature romantic and sometimes campy color-saturated paintings of baby animals and pop stars, McKinniss walks the line between high and low-brow culture.

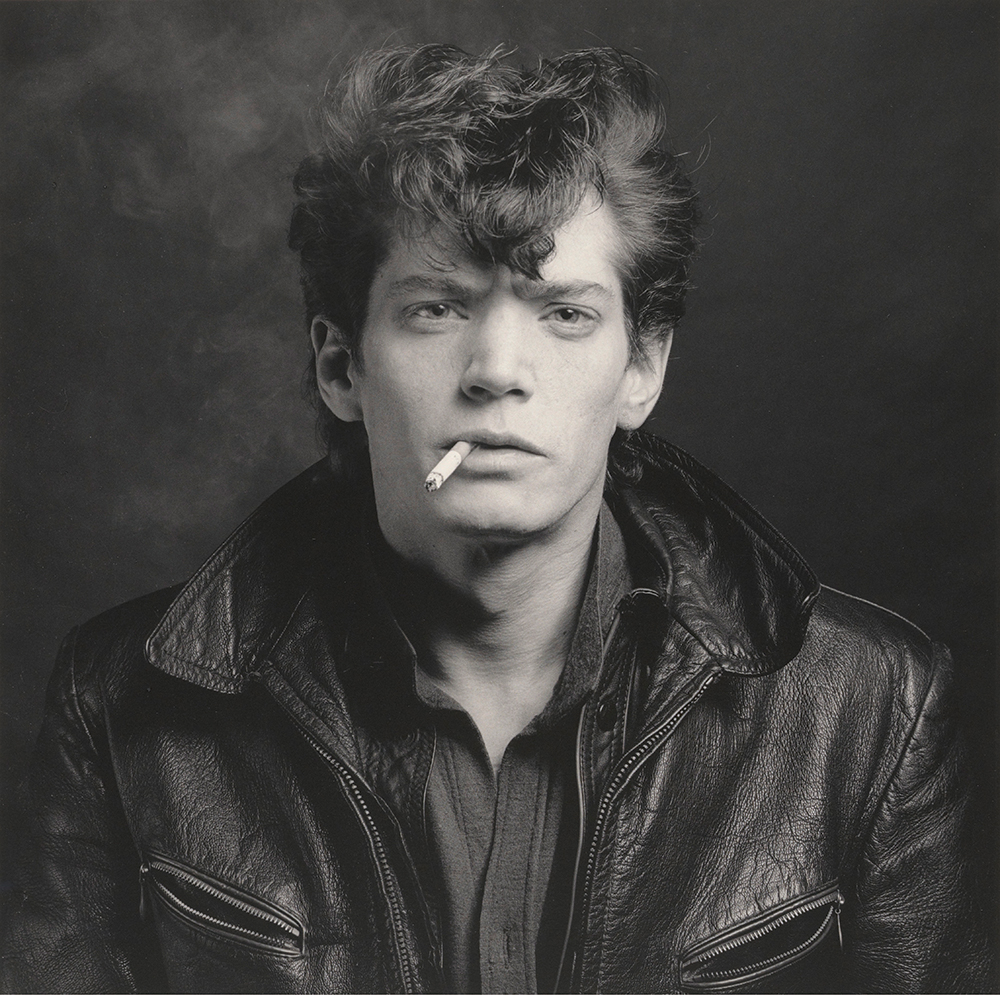

Sweater and Pants by Coach, Shoes and Socks Artist’s Own

Portrait Photography by Tiffany Nicholson | Interview by Anna Furman

Thirty-one-year-old painter Sam McKinniss grew up in a small town in central Connecticut where, as he told me, “there’s an apple orchard and a lot of golf courses and trees and lakes to jump in.” The now Brooklyn-based artist oscillates between sincere admiration for his subjects and a gleeful, ironic take on pop culture–blurring the lines between low and high cultural signs. Disney characters, B-level celebrities, ’80s pop stars, and true-crime characters filter into his work through careful brushstrokes and lush color palettes. In the studio, he listens to baroque opera and pop music (Rostam, SZA, St. Vincent), exclusively.

McKinniss speaks with a sort of world-weary droll, but comes off as anything but–he is attentive to his subjects, and treats each portrait with measured thoughtfulness. On a balmy day in late September, I spoke with McKinniss about his collaboration with singer/songwriter Lorde, the far-reaching influence of late ’60s hippie subcultures, and his upcoming show Daisy Chain in Venice Beach.

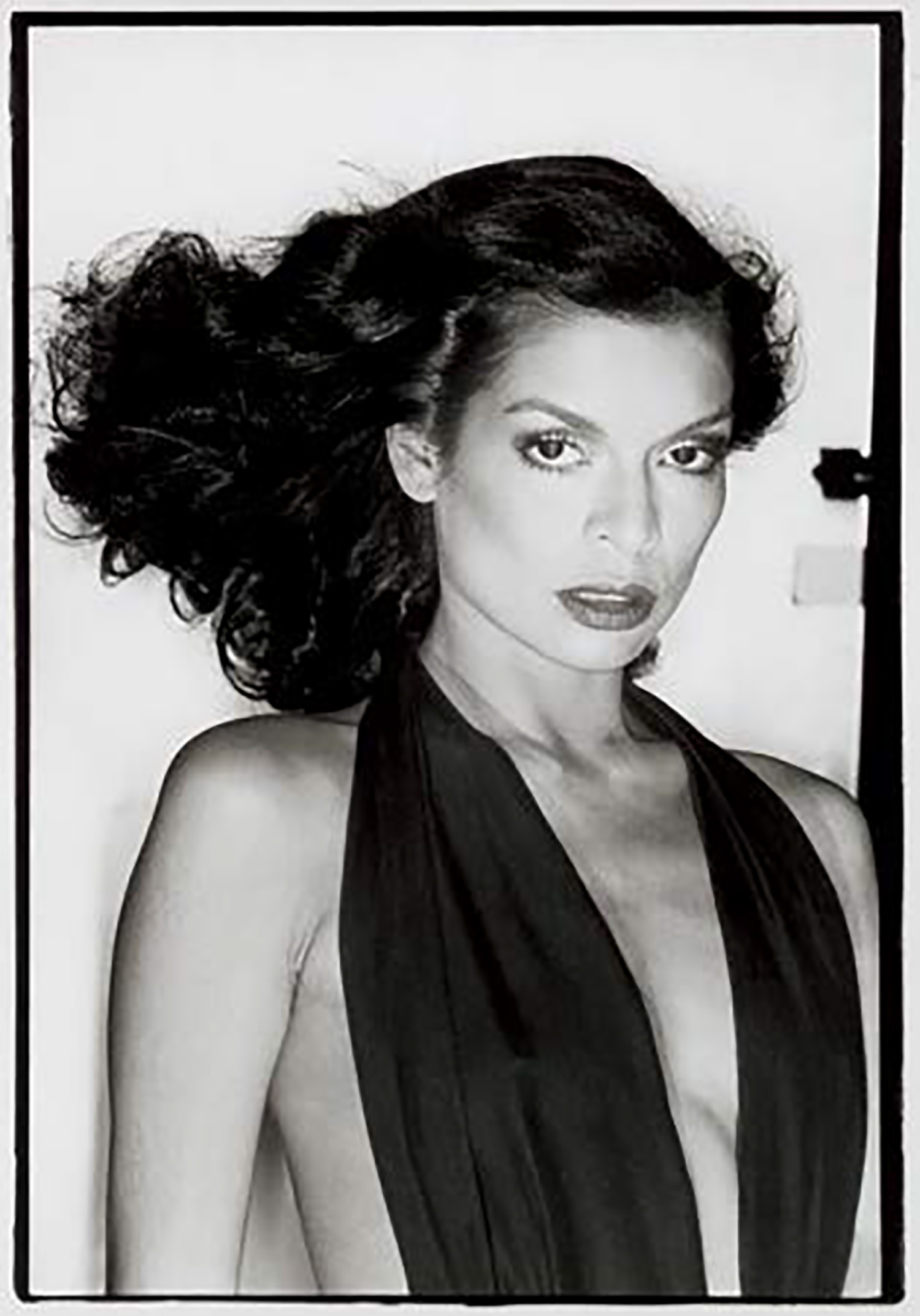

Michael Jackson, 2017

Michael Jackson, 2017

Prince (Under the Cherry Moon), 2016

Prince (Under the Cherry Moon), 2016

Hi! What are you working on today?

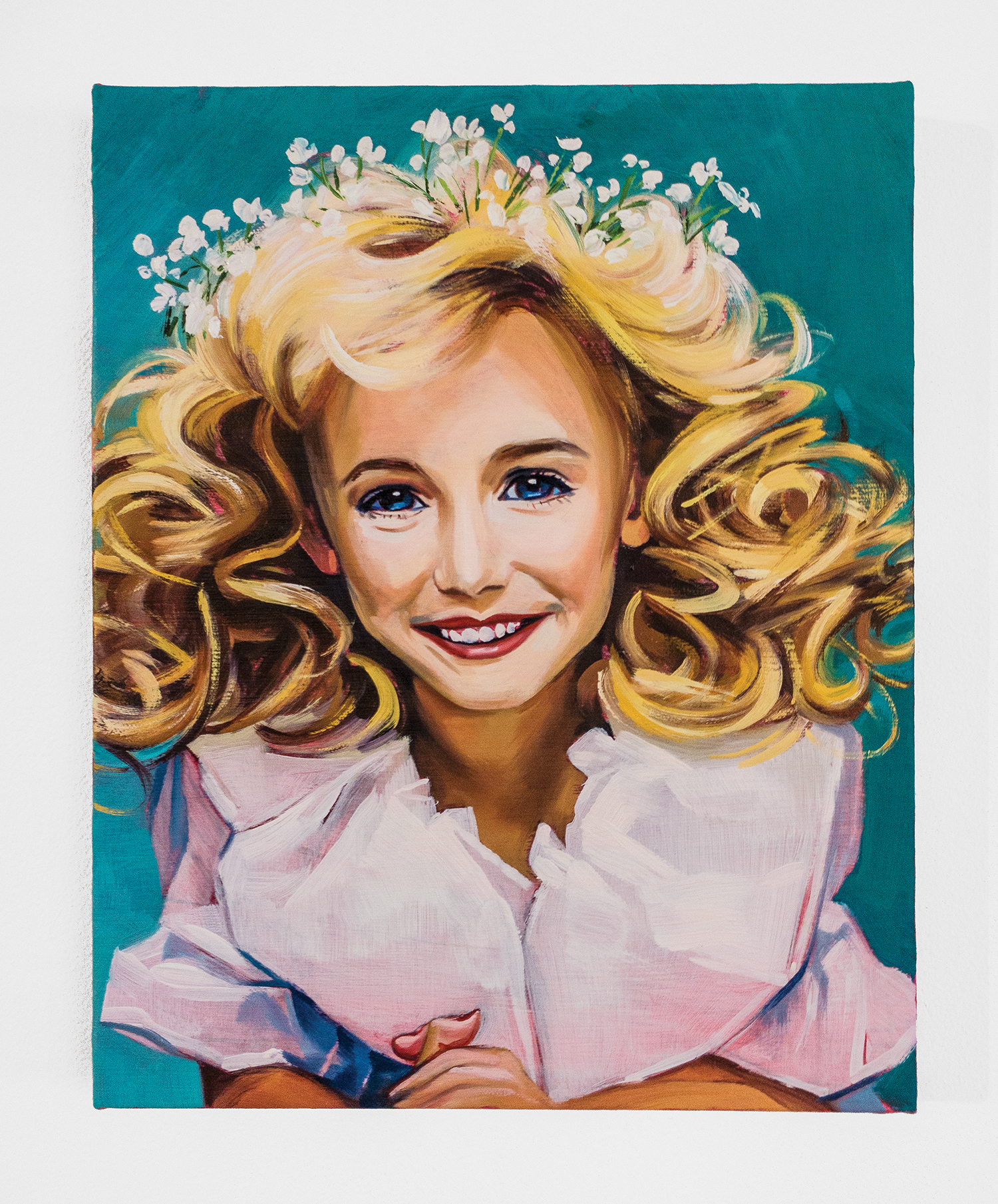

I just started a painting of a lamb smelling some flowers. It’s kind of cute. I recently finished a portrait of JonBenét Ramsey, which might have led me to paint this lamb. She just seems too young to be that made up and that glamorous. She looks so innocent and now she’s so dead–a lamb seems like it would be a nice contrast to her figure.

Maybe generic pictures of cute animals on the internet offset some of the darker, meaner subjects out there or give us some sort of emotional retreat from more violent material.

Tell me about your studio practice.

I like to work every day and I like having a set work day schedule, so I try and start between 10 and 11 and leave by 6 or 7. That way I have time to draw or think out problems, and then look hard at the paintings and decide how they need to be fixed. If I’m going to paint, I need at least four uninterrupted hours. Lately, I’ve been trying to slow down. I want to be a little more thoughtful and courteous to the material. For a couple of years, I would whip through paintings, sometimes finishing one small piece a day. But I’m happier when I take my time and the paint looks better.

What do you mean by “better”?

I mean it in terms of mark-making. Composition–how you design, how you set a picture inside of a rectangle– definitely benefits from taking more time. Every time I hit the canvas with a brush loaded with paint, it’s a succinct moment in real space and time. It can be just one, you know, flick of the wrist. If it’s done exactly right, it looks effortless and the paint can articulate a physical attribute. I’ve noticed that when I’m more patient with a painting, I experience those moments more often. I can touch the canvas with the brush and it sets up gorgeously and it looks like it was just breathed on there. And the paint looks good! It’s important to me that the paint looks good–I want it to be seductive. I want the paint to call attention to itself, almost in an amorous or erotic way. I want the paint to be desired; it has to attract people. It’s sexy when it looks good.

You painted Lorde for her Melodrama album cover. How did that cover project come about?

Last year, a mutual friend put us in touch and she wrote me an email asking if she and I could get together to talk about the album she was working on. She came and visited my studio, saw the work I was making for Egyptian Violet and then described her vision for Melodrama, for which she had total creative control. I agreed to do the cover, which was sincerely a lot of fun for me. The process turned into a very meaningful collaboration.

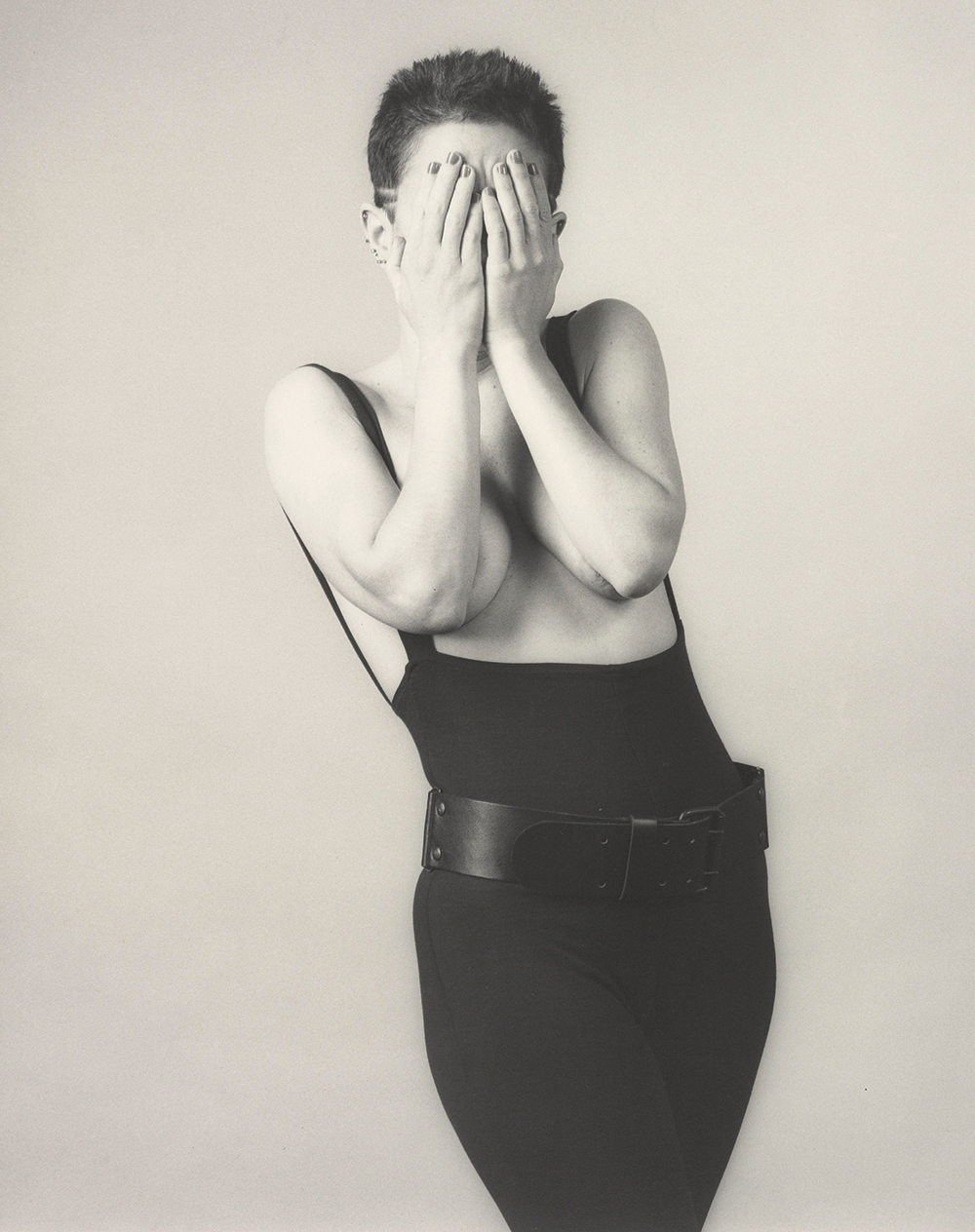

Sweater and Pants by Coach, Shoes and Socks Artist’s Own

If you were to create an album cover image for another musician, dead or alive, who would you choose?

Prince. But what I’d really like is for someone to soundtrack one of my exhibitions. I won’t say who.

You have an upcoming show at Team Gallery in Venice Beach, opening this winter. It’s called Daisy Chain. Where did that name come from?

Well, I like it as a cliché. Poetically or melodically or something, it appeals to me. Also, in Lana Del Rey’s song ”Summer Bummer”, the lyric is wrap you up in my daisy chain. It just seems violent, but also sweet, which basically equals erotic. That album came out in July, which was right when I was getting serious about the focus of this show. Daisy Chain just leapt out at me. It seemed appropriate for the kind of pictures that I wanted to look at and make paintings about.

What are the paintings in Daisy Chain about? Are they mostly portraits?

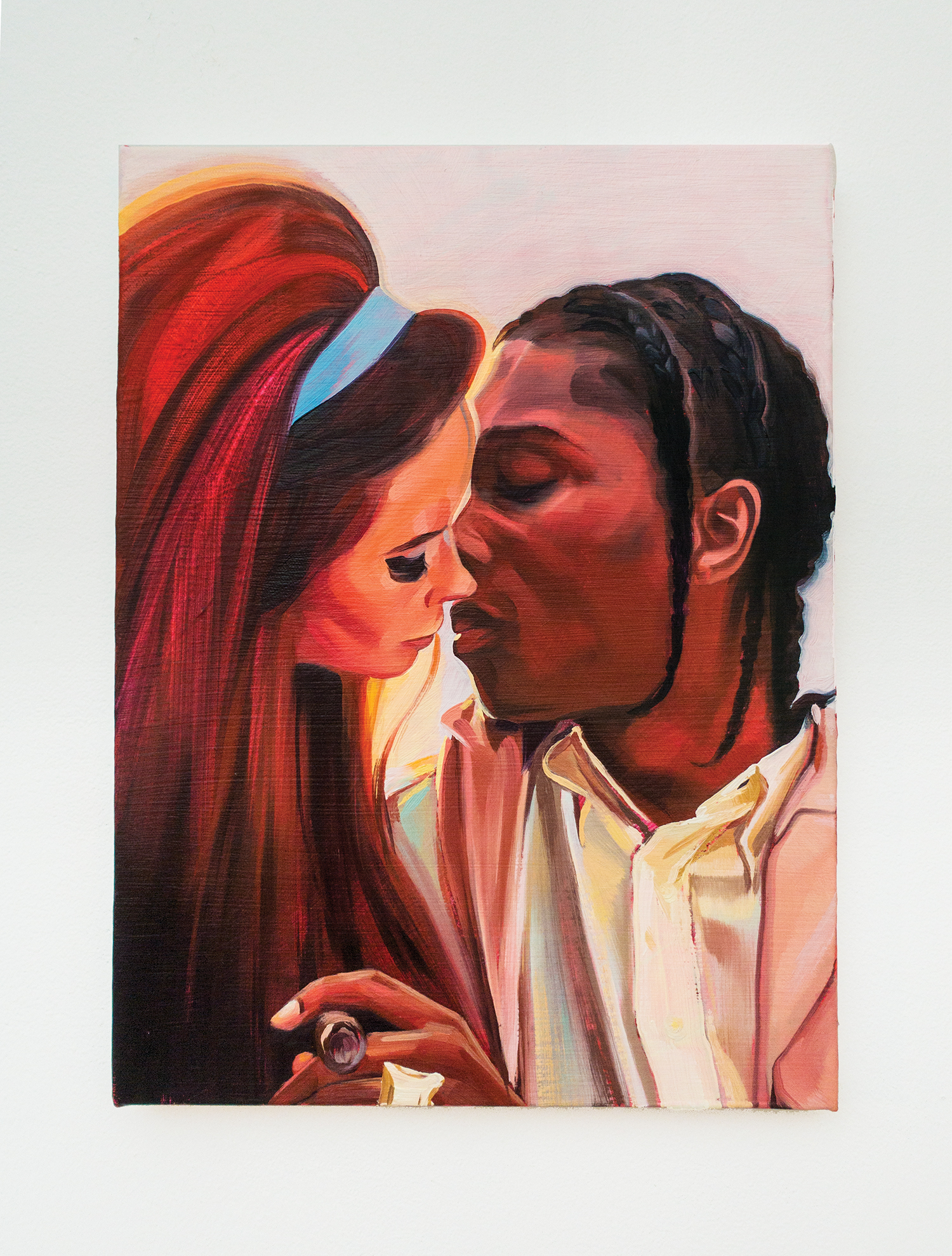

There’s a double-portrait of Lana Del Rey kissing A$AP Rocky that I took from the “National Anthem” music video. There’s a portrait of Drew Barrymore from the mid ’90s, when she posed nude for Rolling Stone magazine. She’s wearing a pixie cut and her hair is decorated with a daisy chain–like, literally a string of daisies. There’s also a portrait of Joan Didion wearing chic, oversized sunglasses–she looks sort of old, severe, and mature. It’s a recent photo, not from the ’60s. And there’s a portrait of Beck taken from the Sea Change album cover, which was made by the artist Jeremy Blake. Oh, I also made a portrait of one of the kids from Lord of the Flies, taken from a paperback book cover re-released in the late ’80s. It was the cover I had when I was in middle school. It’s one of the kids from the island, and he’s wearing a crown of palm leaves or ferns or something.

Did you tailor the subjects of these paintings to fit into a California narrative or did the location of the show affect which subjects you chose to include?

For sure. I was trying to get closer to a California mood. I reread Joan Didion’s The White Album recently and have been listening to a lot of Lana Del Rey’s Lust for Life album. I read Helter Skelter, the true crime book about Charles Manson’s trial, and thought about how some of the murders were committed in Venice. I’ve been thinking about violent crime, mass murder, and how we’re living through such a violent era right now. I don’t know if it’s more or less violent than 1967, 1968, or 1969, but I am trying to organize a group of pictures that could be said to reference 1969. I’m looking for elements of the youth culture that have impressed itself upon my consciousness. I want to invoke–in a vague or nebulous way, which is my way–style signifiers derived from a hippie subculture. I’m wondering if there is a counter-culture and if there are alternatives to our dominant political discourse. Can pop culture have a positive impact on political change? Like, does style equal progress, or can it? I don’t have any answers, but the direction that I’m focused on is one that asks if these celebrated figures affect more than just our understanding of style.

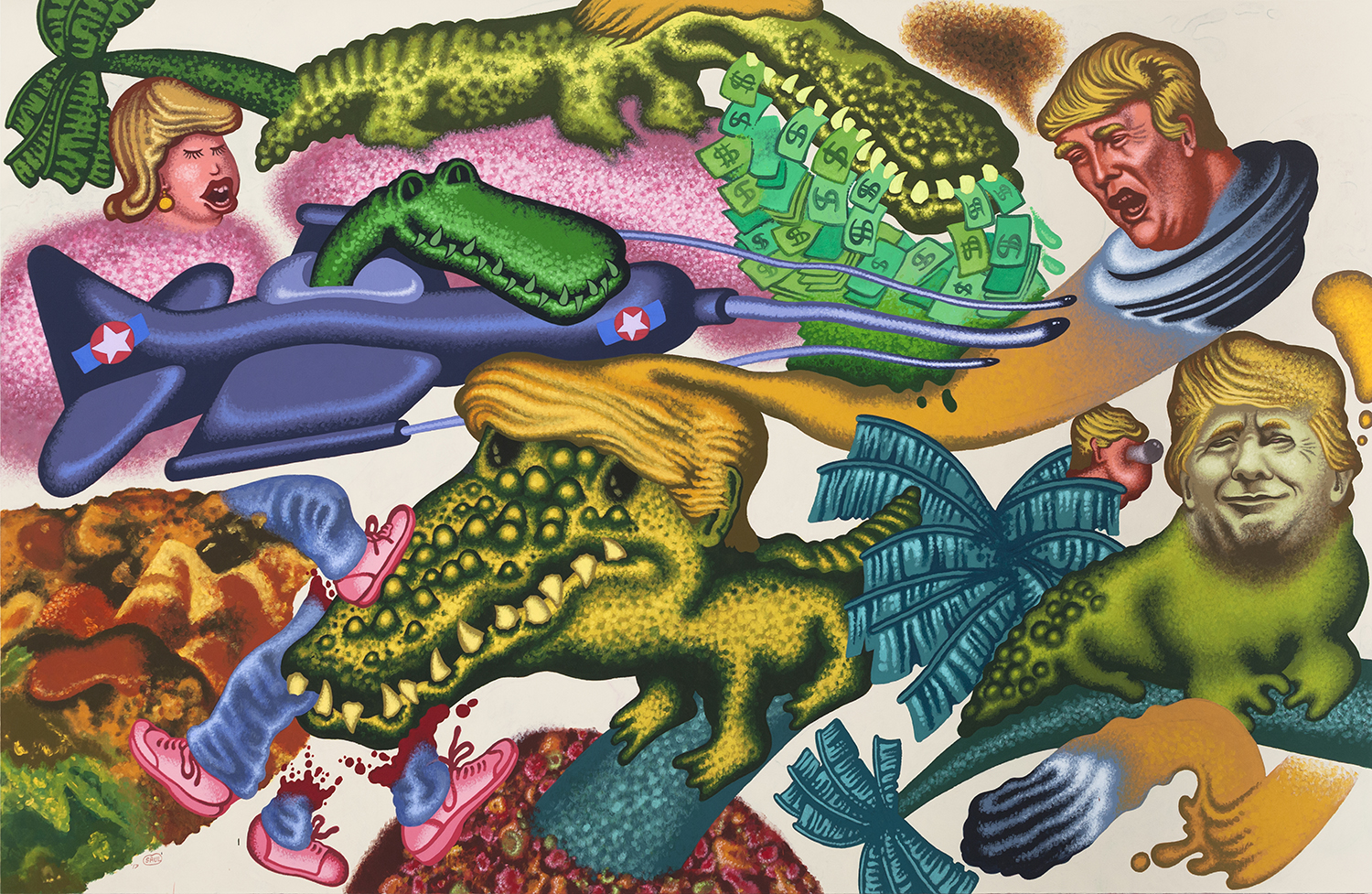

Lana & Rocky, 2017

Lana & Rocky, 2017

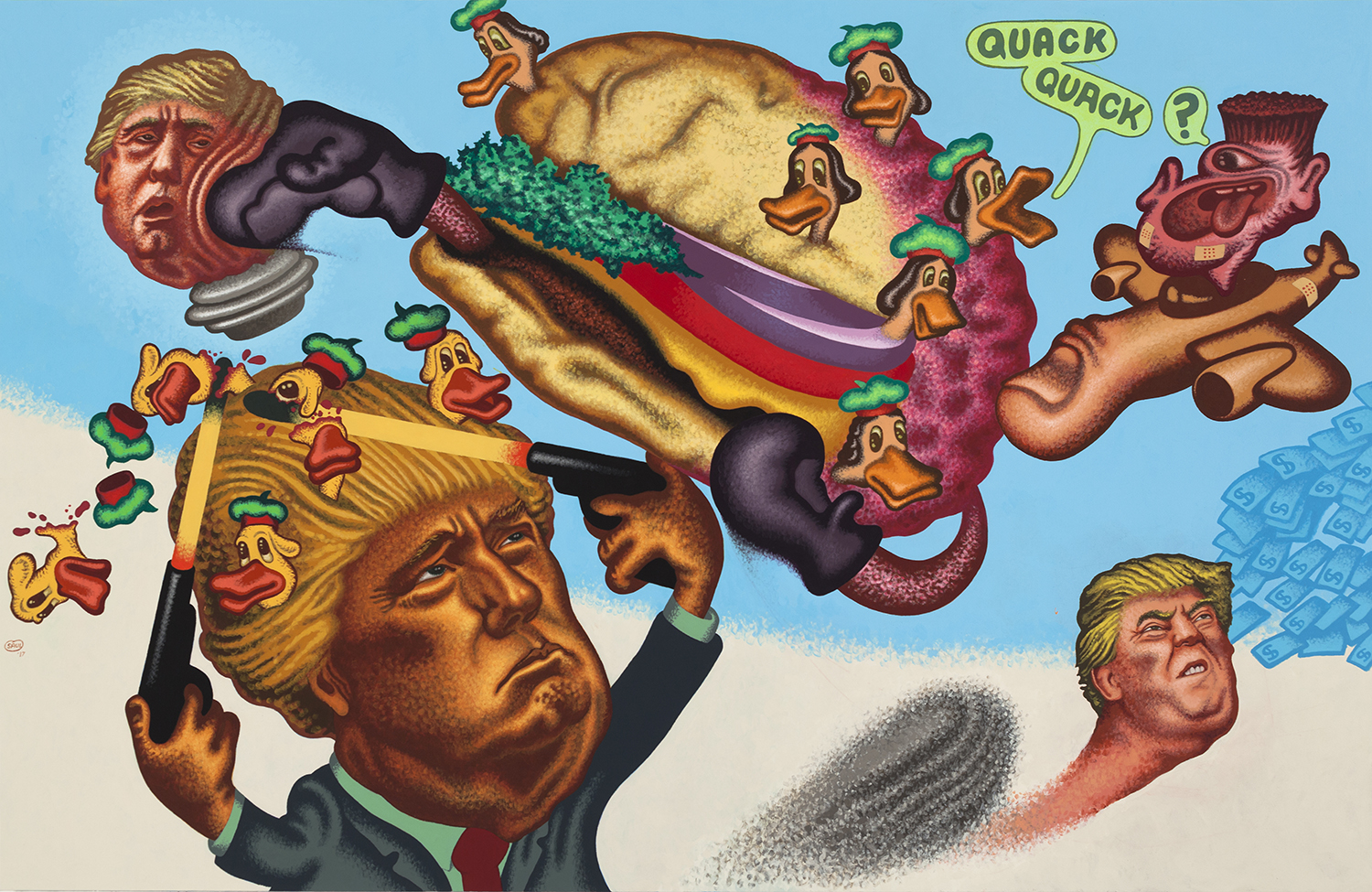

JonBenét, 2017

JonBenét, 2017

In your 2016 show Egyptian Violet, the portrait of Prince was understood to be the focal point of the collection. Is there a painting in Daisy Chain that is comparable – as in the rest of the show hinges around it?

I don’t know if that’s for me to say. I knew the painting of Prince was going to create a stir and that people were going to remember it, but I didn’t know that critics or members of the art world were going to decide that it was the focal point of the show. It has been meaningful, for lack of a better word, to try and conceive of a new show after Egyptian Violet. Egyptian Violet was a darker palette and definitely more of a nighttime art show, whereas Daisy Chain is a little sunnier and a bit more daytime. The floral motif marches through work in both and a daisy is certainly a nice contrast to a violet.

I read that you used to work in a floral shop. Can you tell me about the first three jobs you had?

I worked for a florist for a long time when I was in college, and that was really fun. I did a lot of the dumb gay retail shit that gay guys often get trapped doing, especially if they have a creative degree like a BFA. I also worked at a used and antiquarian book store for a while. That was a good job, I read a lot of books on my lunch break.

Do you paint certain photos as practice? Are there exercises you do to stay nimble before diving into another work?

I took a lot of time off this summer and got out of New York City. I was in East Hampton for two weeks and made, like, 4 or 5 drawings a day. It helped me get thematically and conceptually organized so that when it’s time to go back to work, when I walk into the studio, I know what kind of work I want to make. I like to reacquaint myself with drawing and remind myself that it’s a worthwhile and enjoyable activity. It’s good for my hand, my eye, my brain. Also, I go to The Met a lot to study the paintings. I look at the same works over and over again to try and learn them. To be intimate with them.

Do you remember the last thing you took a screengrab of?

Yesterday I screen-grabbed an image from the New York Times front page of video coverage of the Las Vegas shooting. Horrific. Like a frontier scene by Frederic Remington. Awful. I rarely use photojournalism for my work but I admire it quite a lot.

Have there been any words used to describe your paintings that you either disagree with or were surprised by?

To be fair, no. I think all criticism is fair. I don’t think that an artist totally owns a work after he or she puts the work out into a public arena. Some people understand my work to be about nostalgia. That’s fine. There’s totally an argument for that, but I don’t relate to it. I don’t feel nostalgic for when I was a teenager or for any other time in my life, and it’s certainly not why I make paintings. All the images are taken from some moment that I remember, but I don’t know that memory is the same thing as nostalgia.

Is there a subject that you are interested in making work, but haven’t quite figured out how to approach yet? In other words, what subject is next?

Sure. I do a lot of image-gathering and these images kick around in computer folders. Sometimes I print them out and they sit in literal, physical folders on my studio desk. I shuffle through them periodically. I really want to do a painting of Arnold Schwarzenegger from Terminator 2. It just seems really gross and of the moment–in terms of popular celebrity culture making a parlay into national politics. I’ve been thinking about it for at least two years because it seems loaded, even though it’s kind of a cute movie. It just seems really loaded to paint the former Republican governor of California as The Terminator. Or, Maria Shriver’s ex-husband.

That would be a good title for the piece. “Maria Shriver’s Ex-Husband.”

Yeah (laughs)

Sweater by Coach

Hair by Austin Burns using Oribe, Makeup by Agata Helena @agatahelena using NARS Cosmetics, Art Direction by Louis Liu, Editor Marc Sifuentes, Production by Benjamin Price

All artwork © Sam McKinniss, images courtesy of the artist

For more information visit sammckinniss.com

Costume Institute Benefit on May 7 with Co-Chairs Amal Clooney, Rihanna, Donatella Versace, and Anna Wintour, and Honorary Chairs Christine and Stephen A. Schwarzman

Costume Institute Benefit on May 7 with Co-Chairs Amal Clooney, Rihanna, Donatella Versace, and Anna Wintour, and Honorary Chairs Christine and Stephen A. Schwarzman