A CONVERSATION BETWEEN MARY BOONE AND PETER SAUL

Through her illustrious career, revolutionary gallerist Mary Boone has represented some of the most influential artists of our time. In a rare opportunity, we get to sit in on the conversation between one of America’s best known fine-art painters, artist Peter Saul, and Mary Boone at her gallery located on 5th Avenue in New York City.

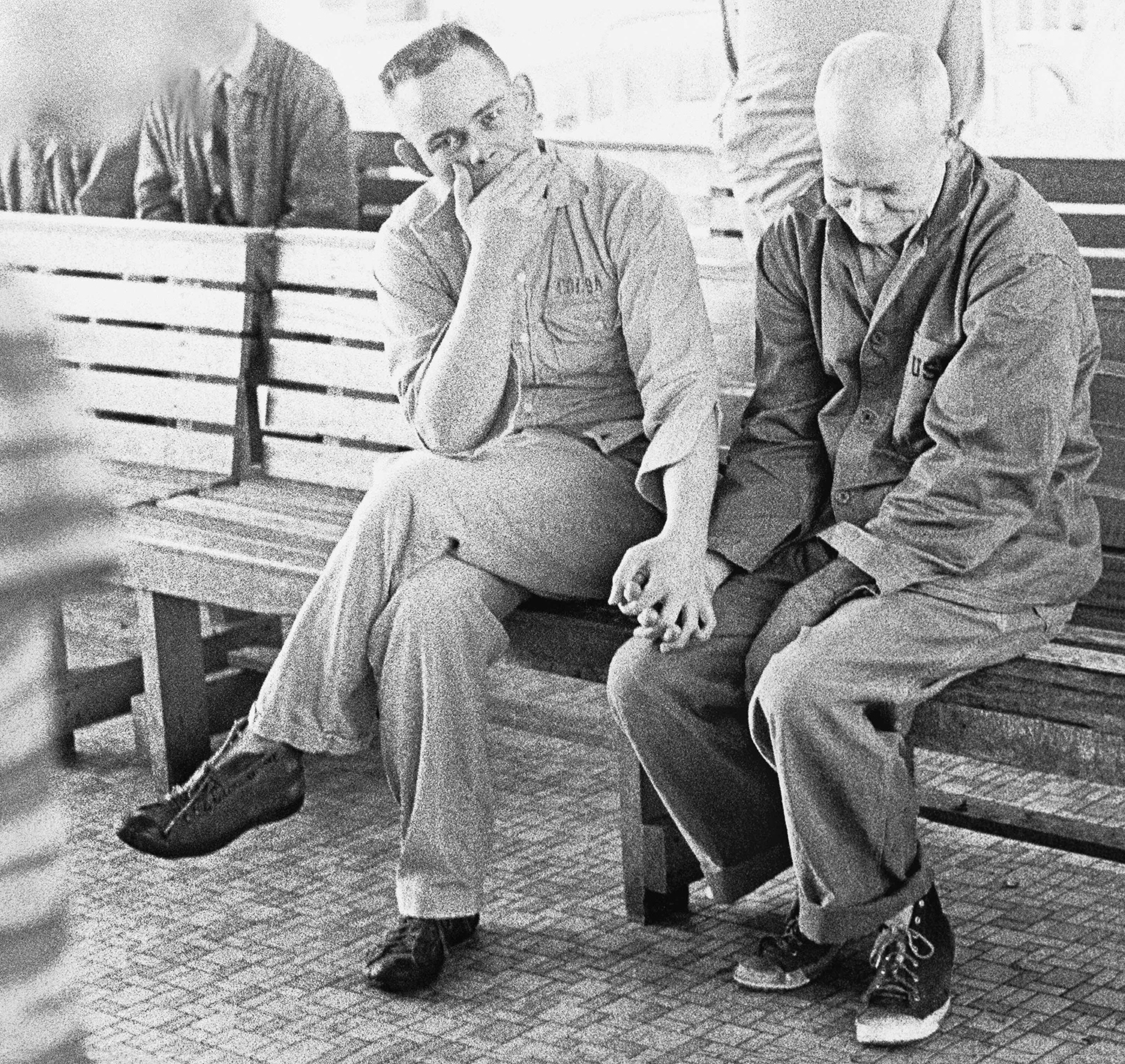

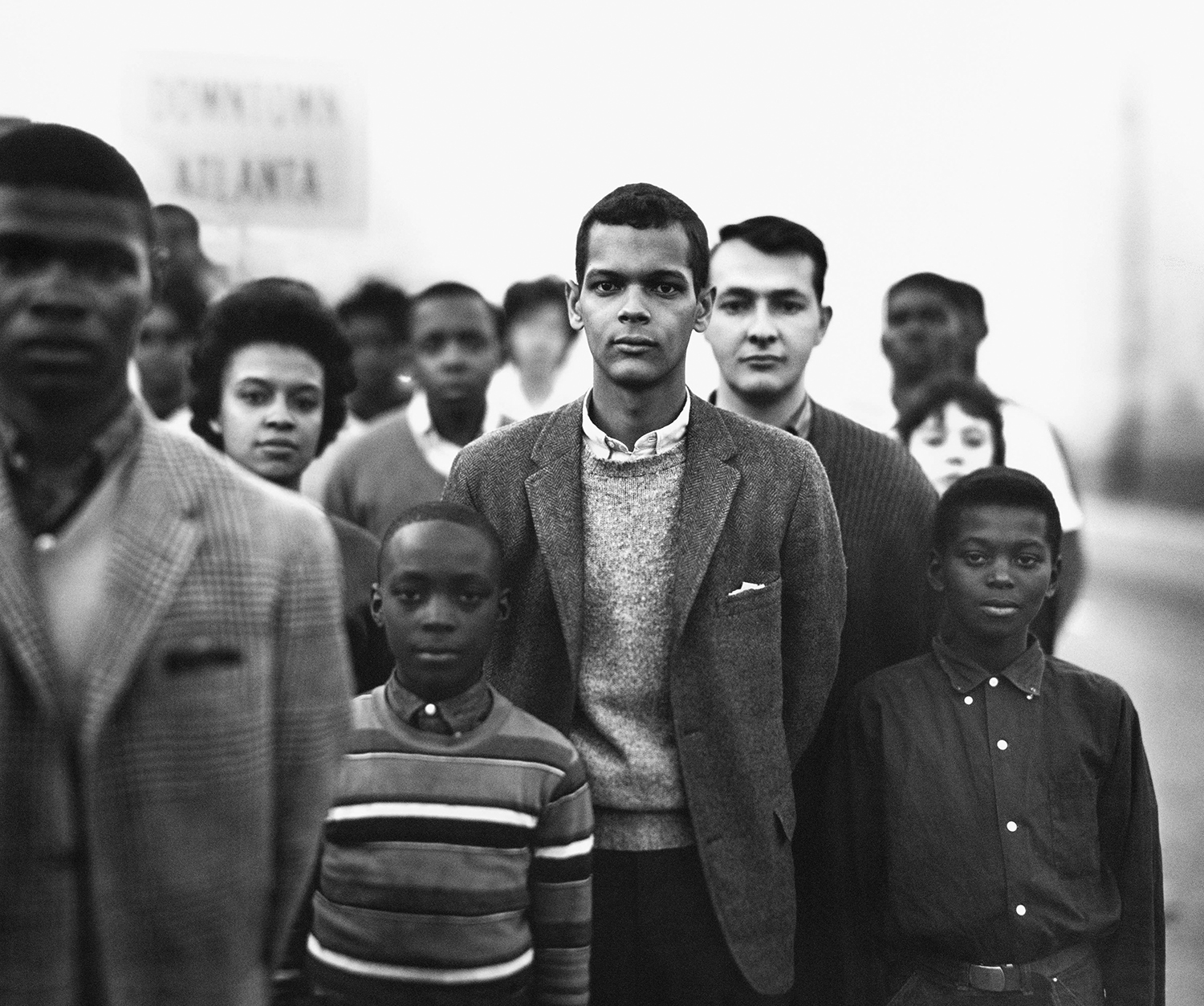

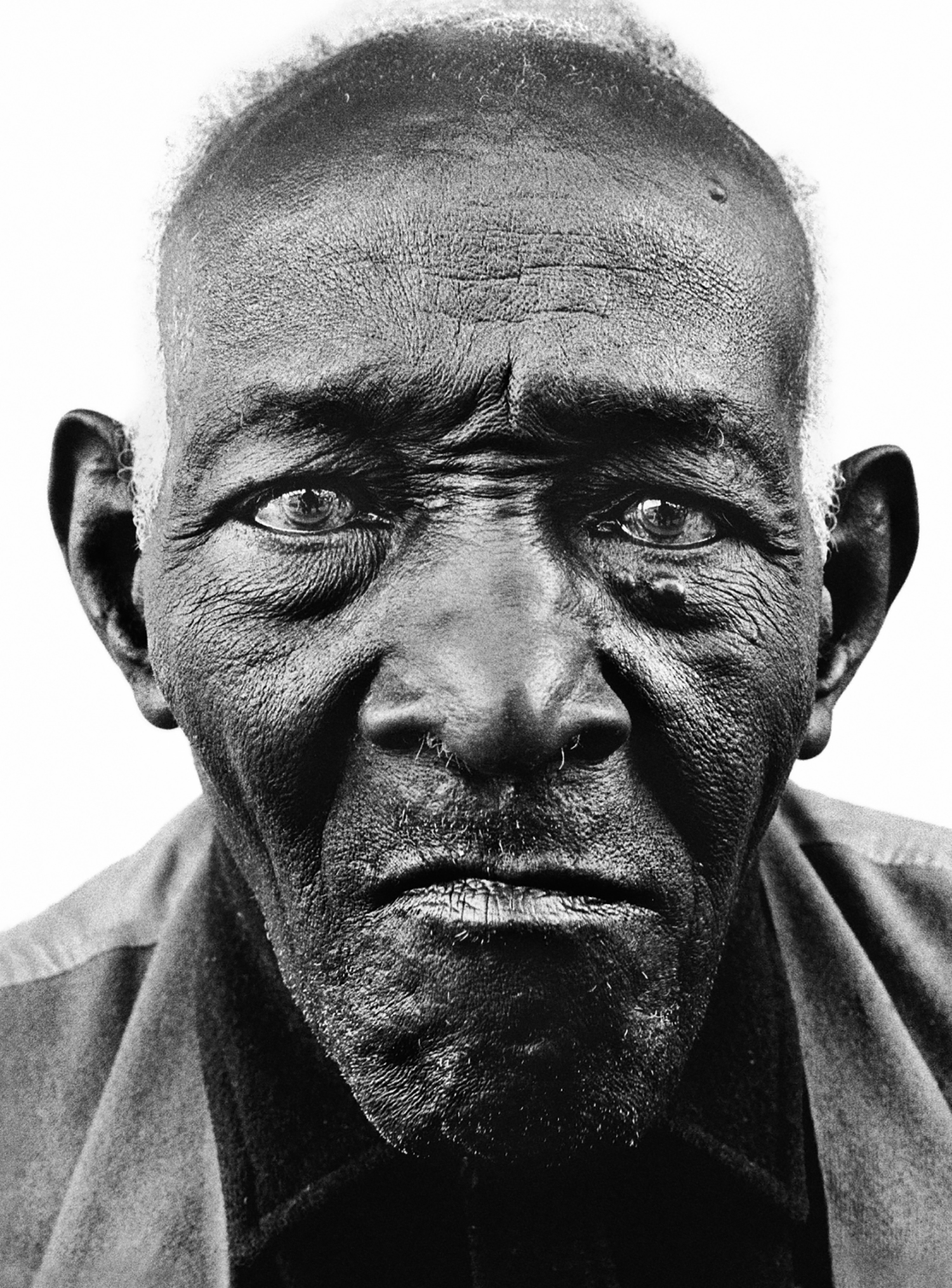

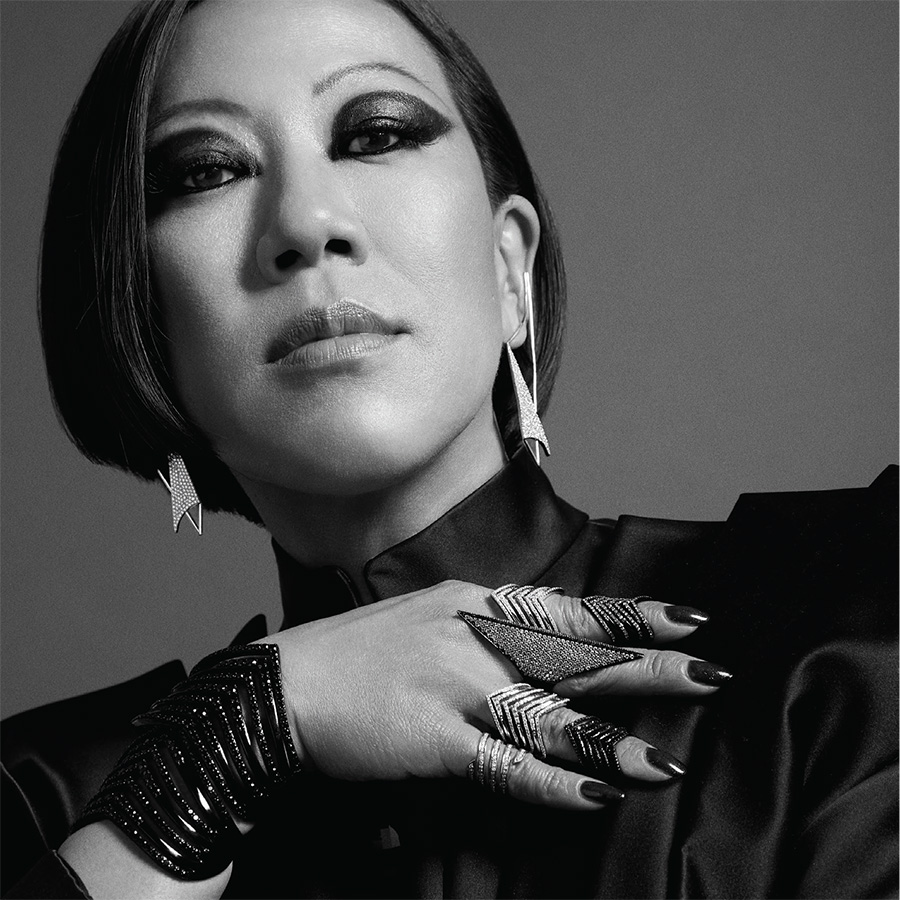

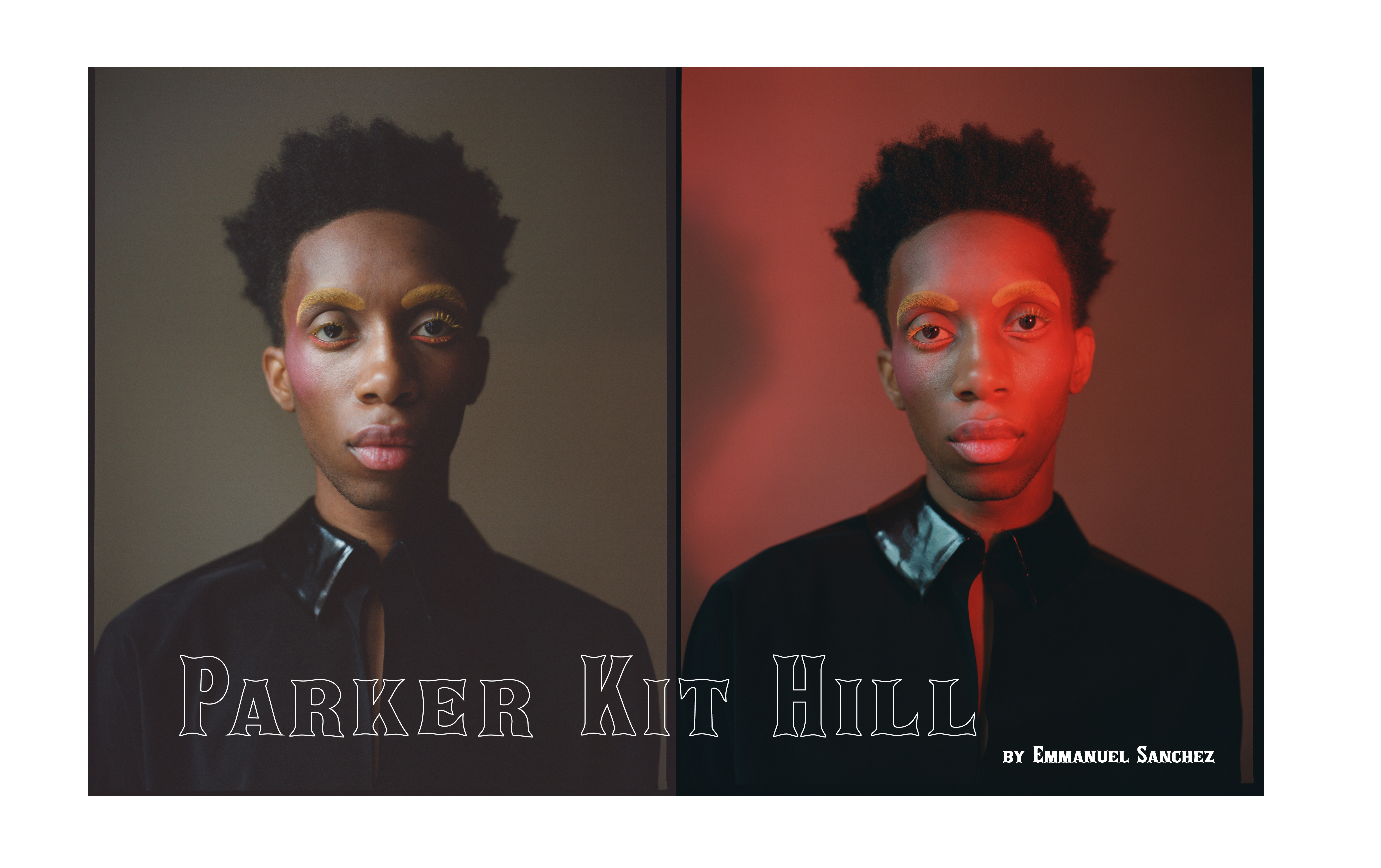

Portrait Photography by Dustin Mansyur

From the beginning of her career, Mary Boone made a name for herself as a brash, subversive, enfant terrible of the New York art scene. David Salle, Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Barbara Kruger, Francesco Clemente, Jeff Koons, and Ai WeiWei all have been represented by Boone. Early in her career, Boone revitalized the New York art scene by creating exhibitions for young, unorthodox, avant-garde downtown artists and giving them a new platform made up of influential international collectors. Boone’s keen instinct and bold moves revolutionized the art of dealing, making her the first to have waiting lists of collectors vying to purchase works yet to be created. New York magazine once dubbed Boone “The Queen of the Art Scene”, and now over forty years later and with two New York galleries that remain internationally respected, her crown remains firmly in place.

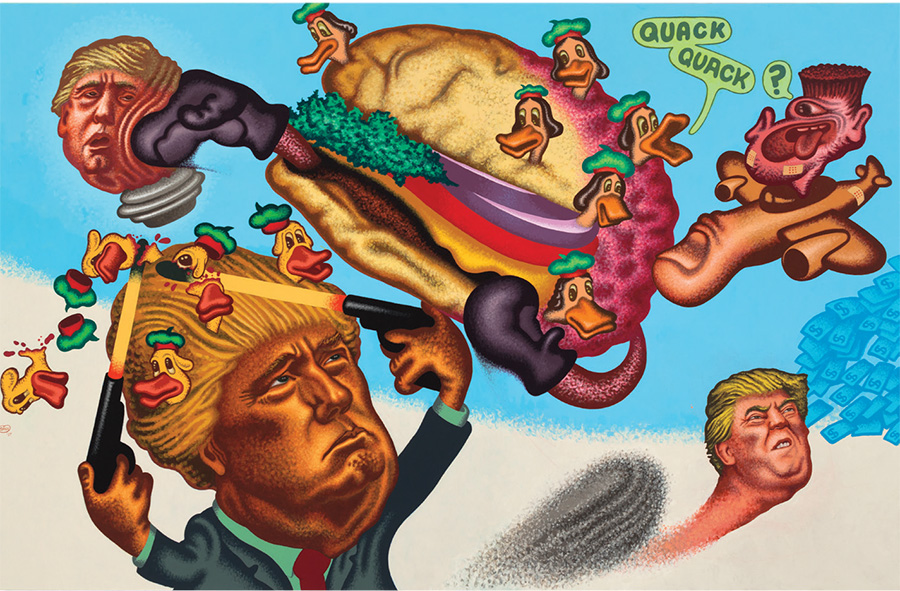

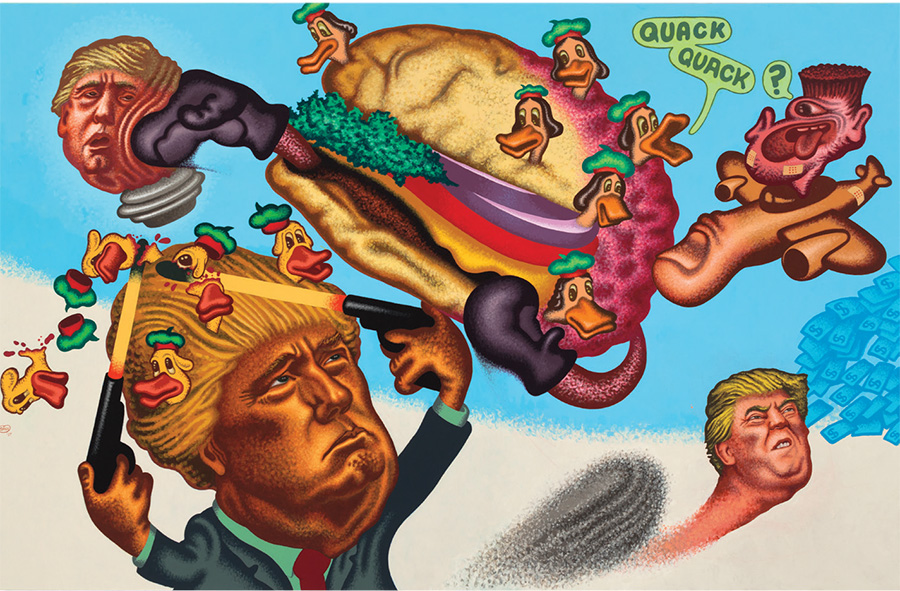

Of the many controversial artists in Mary Boone’s kingdom, Peter Saul, known for his cartoonish lampoon of American political figures and anti-war commentaries, is perhaps one of the leading contenders. Saul’s fantastic representations of American politics painted in his signature psychedelic, hyper-saturated palette, paired with historical influences and intellectual irreverence, have opened the interpretive, and at times controversial, dialogue between politics and pop culture. Educated in Europe in the 1950’s and keeping his art career under theradar through most of his life, Peter Saul found a champion in Mary Boone, who helped him claim his rightful title as one of the top contemporary artists in the US.

In the library of her uptown gallery in New York City, Iris Covet Book captured a conversation between the notoriously pressshy Mary Boone and Peter Saul as they discuss the history of the gallery, the politics of fine art, and painting Donald Trump.

So, Peter, to start from the beginning, you began your career in Europe in ‘56, correct?

Yes, and I started showing here in New York in 1962; it was my first show in New York City. I’ve been showing all these years but it hadn’t been appreciated until recently. I’ve had some success in Europe over the years, which is great. That’s really kept me going a lot of the time. In the ‘90s I sold a lot of work in Europe, very inexpensively, but for a college professor it seemed like a miracle of finances. Like, “Wow, 20,000 bucks!” You buy a new car and it’s just wonderful. I didn’t look any further than that. I suffered from modesty somewhat, and now I’m much less modest. Now I grumble at small amounts of money. (laughing)

My early days as a gallerist…I mean it was really a hard struggle too. People kind of think it must have been really glamorous. I worked as a secretary at Bykert for Klaus [Kertess], then the gallery closed and I went off on my own in ‘77. And when I was at Bykert, I met an artist named Ross Bleckner. I put him in a group show in Bykert, and he was showing with me and with Paula Cooper. In those days artists would try different galleries and find which one sells, which one fits. So when I opened my own gallery, he introduced me to a lot of his friends from CalArts, and that included David Salle, Eric Fischl, Barbara Kruger, Julian Schnabel and Jeff Koons and a lot of other artists. So, I met artists through word of mouth from other artists.

But you have to remember that at the time no one believed in any of the artists I was showing, no one believed in them. No one wanted to see them or hear about them. They were either unknown or too hyped. People didn’t believe in Schnabel or Basquiat or Sally or Fischl, or even Brice Marden. Jean-Michel [Basquiat] and I met when he was 19; he decided he wanted to show in my gallery because he wanted to show with all these other artists who he thought were really good artists. And I was really very, reticent, like, “Is this right?” but he was really a wonderful person, so sweet to me and really a good artist. I showed Francis Picabia in 1983 and got a scathing review from The Times about it.

They’re so dumb!

They said it was a terrible show and that I was just trying to trick the art world. There was this conspiracy theory that I was making fun of art or artists, but eventually they started to believe in them.

It is easy to kind of glamorize things in retrospect, but mostly I like artists that are challenging. I mean, you are challenging. Even though you were not young chronologically, you were really young as an artist. The paintings weren’t just flying off the wall like they are now. It was hard to sell them, but to me you are such a master and such a forward thinker; everybody should want to be grabbing them up. But it takes a long time to make an artist. How were you exposed to the art world in your early career?

Well, I met [art collector] Allan Frumkin, he was very important to me. I accepted a certain amount of money every month for my work. He would show up one day of the year and pick which pieces of mine he wanted and then leave again, and I could do whatever with the ones that were left. This lasted for about 30 years; it was a long relationship. From 1960 through 1990. The last time he arranged a show of my work was ‘97 I believe, so this is 37 years of activity. During this time I took the opportunity to not mess with business. I just enjoyed my life. Unfortunately, I was looking backwards when I decided to be an artist in 1950. I was looking to the 19th century: you have a lot of cigarettes to smoke, wake up late in the morning, work on your picture, there is a beautiful woman in your life, there is a room you call a studio, you look at the painting, and that’s it. That’s your life, you know. You don’t worry about any business or anything, and I was encouraged in this attitude by my art teachers.

My life was very simple, and not lived fully up until the decision to move to New York City in ‘97, and I thought “Why not normalize my career?” I realized at that point it depends a lot on the artist. You have to present yourself to the buyers, and I hadn’t done this before. I simply hadn’t shown up. I did everything I could to make my paintings attractive and interesting, but I personally didn’t show up, hardly ever. This was weird, and I suddenly realized this was weird, so I said [to myself ], “Hey, from now on, be normal.” So, we showed up. By then I was with Sally, we were in Austin, and I retired from my job at age 66 and came here to proceed with you.

Peter Saul, Nightwatch, 88” by 128”, acrylic/canvas, 1974-1975 ©Peter Saul. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Peter Saul, QuackQuack, Trump, 78” by 120”, acrylic/canvas, 2017 ©Peter Saul. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York

We were meant to be.

A lot of it is just showing up and being a nice person. Sally and I show up, we’re nice people, we get along, and that is very attractive because most of the time artists who are married don’t get along. I didn’t know this, but this is the way it is. This has helped us to be liked by important people in the art world who think we are attractive to work with because we get along with each other. It’s crazy, but it’s the truth. You have to be a nice person.

That’s true!

It’s not enough to make an interesting picture or whatever.

Do you think the newfound appreciation you’ve been experiencing has to do with the times?

I guess so.

I remember remarking at your first show that the average age of the audience was like 22. There was us and then all these 20 year-olds. You have become a mentor to a lot of young artists.

It’s true. It’s a blessing; it’s a good sign.

In speaking of mentorships, influencing and teaching, are there any important mentorships or up-and-coming young artists that you are working with, Peter?

Well for example, Erik Parker is an artist that was in my art class, he showed up at some point in the ‘90s and is now in the art world. He has shown some flexibility, he’s stuck around, and he is now going to have a show at this gallery. So I have him and others from Texas. I don’t know… people introduce themselves to me and say, “I remember your art class!” and then say something I never would have said, but that’s okay, I just let it pass. I don’t concentrate on what has already happened, I try to keep my mind open for the painting I’m working on and that’s pretty much it; I’m not a historian.

Well that’s good, because then you’re not looking in the past, you’re always looking forward.

Yeah it’s important not to get hung up. If you’ve been around for 40 or 50 years, it’s easy to begin getting interested in research into those years, and what did you do and all of that stuff, but that’s deadening. Likewise, I like to show at a gallery where there is one person in charge and it’s not a corporate thing. What I don’t like is when a gallery has a selection of people that is based on age and gender and stuff. When they’re like, “Well, we have four male artists in their 70’s, so we got enough of them. Let’s get three women between the ages of 30 and 40.” That kind of thing is nonsense. I like the individuality of this gallery, that’s why I’m here really.

Oh, I love that you said that! I do think of artists in terms of their individuality, I’m not trying to make a movement. So many of the galleries now are going towards assigning different staff members to artists, and I think it is impersonal. I always thought the greatest thing was becoming friends with the artist and having a relationship.

Yes, we want to, sort of, “skip” the corporate scene, don’t we?

I think that it’s ruining the art world. What are your thoughts on the art world today?

Well, I’m seeing a lot more shows than I want because my wife, Sally Saul, who makes ceramic sculpture, is extremely interested in art and what’s going on. She insists that I see a lot of shows. Today we’re going to the Outsider Art Fair, I think, and then to the Tom Laskowski opening, and then a group show where a painting of mine that belongs to Joe Bradley is being shown. Sally insists on a certain number of days a month we go see art. So, I see more art.

And you live in Germantown, so you have to travel a couple of hours to get here.

Yeah, but it’s relaxing to be on the train. You want to take a pause often from the painting so you can rethink certain areas that you’re working on. Painting for me is a slow thing, it gets done in various stages, it develops. And the next development came clear to me this morning so it can happen tomorrow.

We had a chance to show your recent Trump pieces a few months ago. What has the response been to them and have you experienced any backlash?

No, I don’t think so. I’ve treated Trump tenderly compared to the other Presidents I have painted. The most psychotic looking one was actually one of the first, Nixon. I tore the guy apart like he was in the hands of a serial killer or something: bad news. I hope for no particular response, but Trump is a good subject. I didn’t vote for him anymore than anyone else I know. 83% of New York voted for Hillary. I don’t know why she isn’t President. She won the election, but because of the electoral college she isn’t sitting in the Oval Office. As far as I know, Trump is not aware of me. He probably thinks of me as some loser artist. He looks at my prices and goes “This is cheap! He’s a loser, he’s a loser!”

“It’s fake! It’s fake art!” (both laughing)

No, but I’m not looking for trouble. I’m looking for subject.

For more information visit maryboonegallery.com

Coat by

Coat by