TARAJI P. HENSON

Taraji P. Henson and Pam Grier talk shop on their shared experiences playing formidable roles for women of color, executing death-defying stunts, and uniting women in entertainment.

Dress by Alexandre Vauthier, Hat by Eric Javits, Stay-Up Tights by Falke, Shoes by Aquazzura

Interview by Pam Grier | Photography by Alexander Saladrigas @ Cerutti and Co | Styling by Ron Hartleben

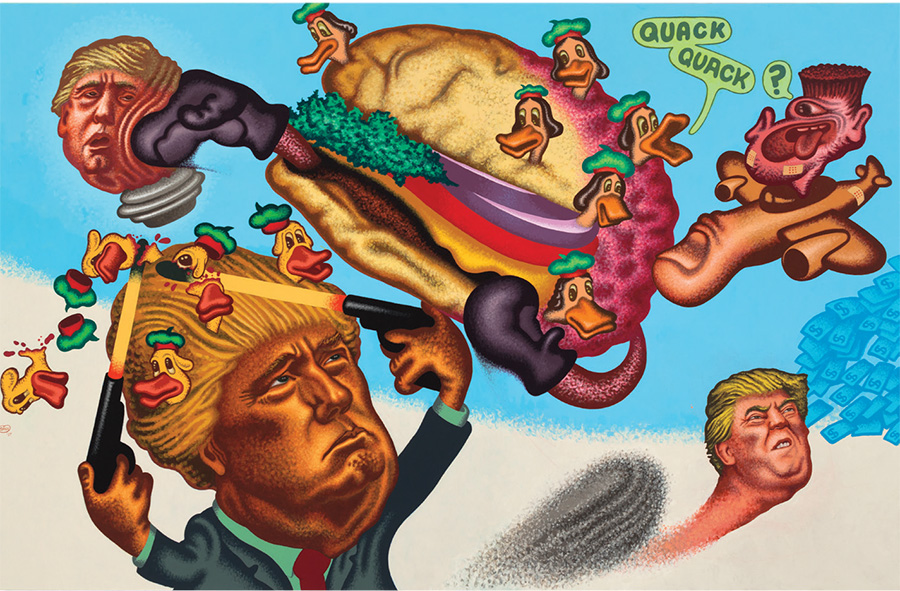

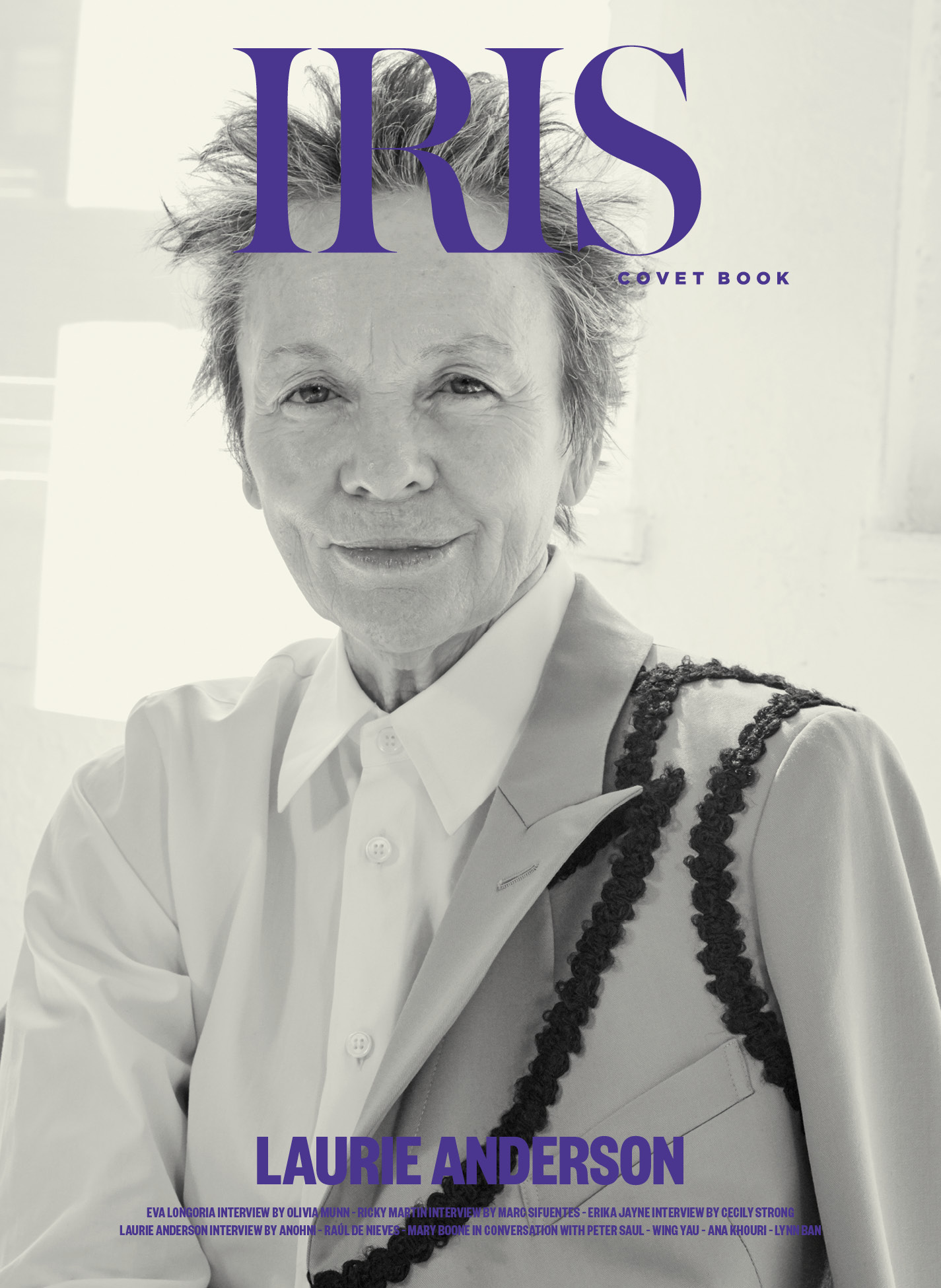

Taraji P. Henson is a typhoon of energy when she arrives curbside at the Plaza Hotel for her cover shoot. With an entourage in tow, Henson’s seven-day work weeks are the new normal for an actor in such high demand. Rising to fame years ago with her Academy Award nomination for her lauded role in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Henson proved with her talent and tenacity that she had staying power. Now, beloved by Empire fans as the one-and-only Cookie Lyon, Henson’s take on the badass-boss-queen character earned her a Golden Globe, Critic’s Choice Award, and two Emmy nominations, as well as fashion-cred from her fans for her character’s memorable high-drama designer looks. Gaining international recognition and several awards and nominations for her role as NASA scientist Katherine Johnson in the historical drama Hidden Figures, it’s evident that Taraji brings a range and depth to her characters that incites a devoted audience, and garners accolades of esteem from an industry that has an infamous history of shortchanging roles for women of color.

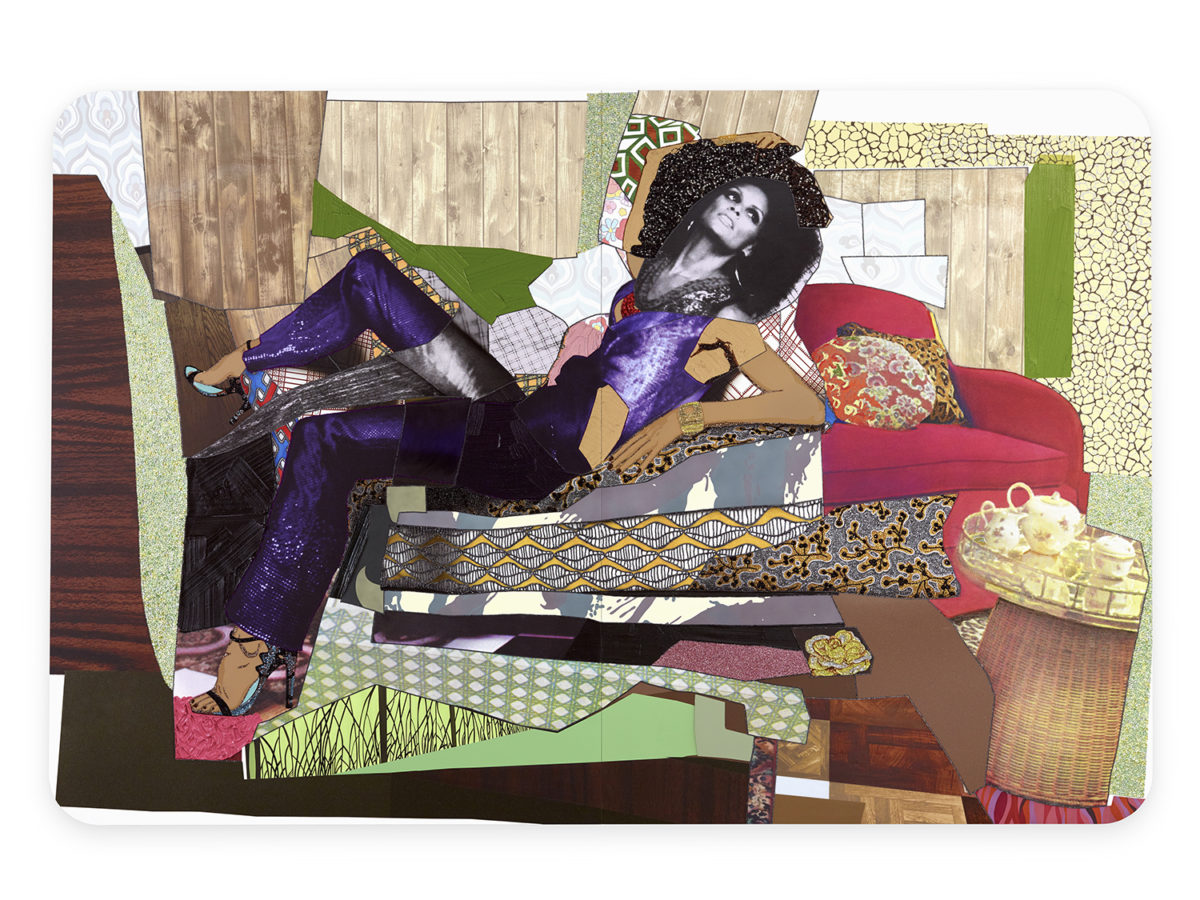

After years of working odd jobs as a Pentagon secretary and a singing waitress while completing her degree at Howard University, Taraji moved to Los Angeles to pursue her dream of becoming an actress. With her young son Marcell accompanying her, Taraji juggled being a mother while working as many roles as she could – a work ethic she refuses to shake to this day. Through her years in Hollywood, Henson has grown a thick skin and learned to adapt to the ever-changing landscape of show business, building off of the foundation laid by the women who came before her, and adding her contribution to the empowerment of women in entertainment. Dressed to kill in the upcoming action thriller, Proud Mary, as a hired hit-woman, Taraji chooses yet another career-defining role, pushing the envelope while balancing the razor wire between her signature bulletproof strength and intrepid vulnerability – something she’s managed to turn into a touchstone of her work.

One pioneering actress who helped pave the way for women of color in entertainment is legendary cultural symbol, Pam Grier, known for her iconic roles in Foxy Brown; Coffy; Sheba, Baby; and Jackie Brown. Here she interviews the newest face of black female action stars: Taraji P. Henson, for an IRIS Covet Book exclusive.

Jacket by Michael Kors Collection, Jewelry by Marc Jacobs, Stay-Up by Wolford

Coat by Landlord, Bra, garter and underwear are Vintage Christian Dior at My Haute Wardrobe, Stay-Up Tights by Wolford, Shoes by Manolo Blahnik

Coat by Landlord, Bra, garter and underwear are Vintage Christian Dior at My Haute Wardrobe, Stay-Up Tights by Wolford, Shoes by Manolo Blahnik

Taraji, how are you? Girl, congratulations I am so happy for you! I can’t wait to see Proud Mary.

Thank you, thank you! I can’t wait to see it either–we’ve just finished shooting.

Well, the trailers look fantastic! And to see that 50 years later is overwhelming because I was out there by myself, I was just trying to show an example of our culture, our black women, who we are. This is who we are. Nothing can stop you. You have wings, spread them.

Yes, ma’am.

When you won your Golden Globe for playing the role of Cookie Lyon on Empire, girl, I think I screamed louder than you! What does Cookie mean to you? How much do you identify with Cookie’s character?

I think what I have in common with Cookie is her fight; you’ve got to fight to be in this business, especially as a woman, and a woman of color. You’re always fighting. So, I think I have that in common with her for sure. The mother lion… I identify with how protective she is of her family. I identify with how protective she is of her family. I identify with what she will do for her family, the great lengths she will go for her family. Cookie chose to go to jail to save her boys from becoming a statistic in the hood. She didn’t want them selling crack like she did. She sacrificed her freedom for her family. Now, I don’t know if I would sell drugs for my family. That side of Cookie, I have to find another way to hustle! (laughs).

At the same time, I grew up in the hood. I grew up in the ‘80s, and I remember when crack was dropped off in the hood, so I can understand her thinking. Your [tax] refund, your McDonald’s income, or working at the grocery store as a clerk are not going to do it. So I understand your back being pushed up against the wall and that’s all you’ve got; I get it. But growing up in the hood, I saw all my friends who chose that path, and well…I couldn’t. That life was not enough for me, I needed more. I chose to go the tough route.

That’s where Cookie and I are different. I had friends in the drug gang, but I chose not to be. I chose to work doing data entry at 16-years-old making $4 an hour. I didn’t want to risk my freedom because I had things to do, and I knew there were other ways to be successful. There are other ways to accomplish your dreams. But I still understand her, that’s why I didn’t judge her. As an actor, you can’t judge. At first, she scared the hell out of me. I was like, Oh my God, this character is crazy. The viewers are going to hate me. Black people are going to be like, Why did you make us look like this? And then, you know, I peeled back the layers and found her truth. I thought if I play her truth then the audience will empathize with her, they will understand her, and they will understand why she made the choices she made.

And now you’ve got the support and they are moved, touched, and rooting for you! Sometimes as we work, there’s so much going on from scene to scene that the audience doesn’t get a chance to really absorb or savor all of those elements that you just described as the actor.

And especially on TV. I mean, you have to follow the series because you only have 43 minutes to tell a story. The beautiful thing about TV is that you get to watch each episode through the series and track the character’s journey and struggle. If I feel like I can’t bring the truth to a character, then it’s not the job for me. I’m not the only actress on this planet. There’s enough work for all of us. (laughs)

That was my philosophy as well! It’s a beautiful platform to have. When I would be working on a project and I would be sent scripts, sometimes I’d say, “You know who’s good for this? Vonetta McGee. Send this to her.” We always shared, and there weren’t that many movie roles.

I also wanted to welcome you to the “Action Woman’s Club!” You’ve got to tell me about Proud Mary, who she is, and the challenges you faced playing her. Now this looks like you’re going to take some blood!

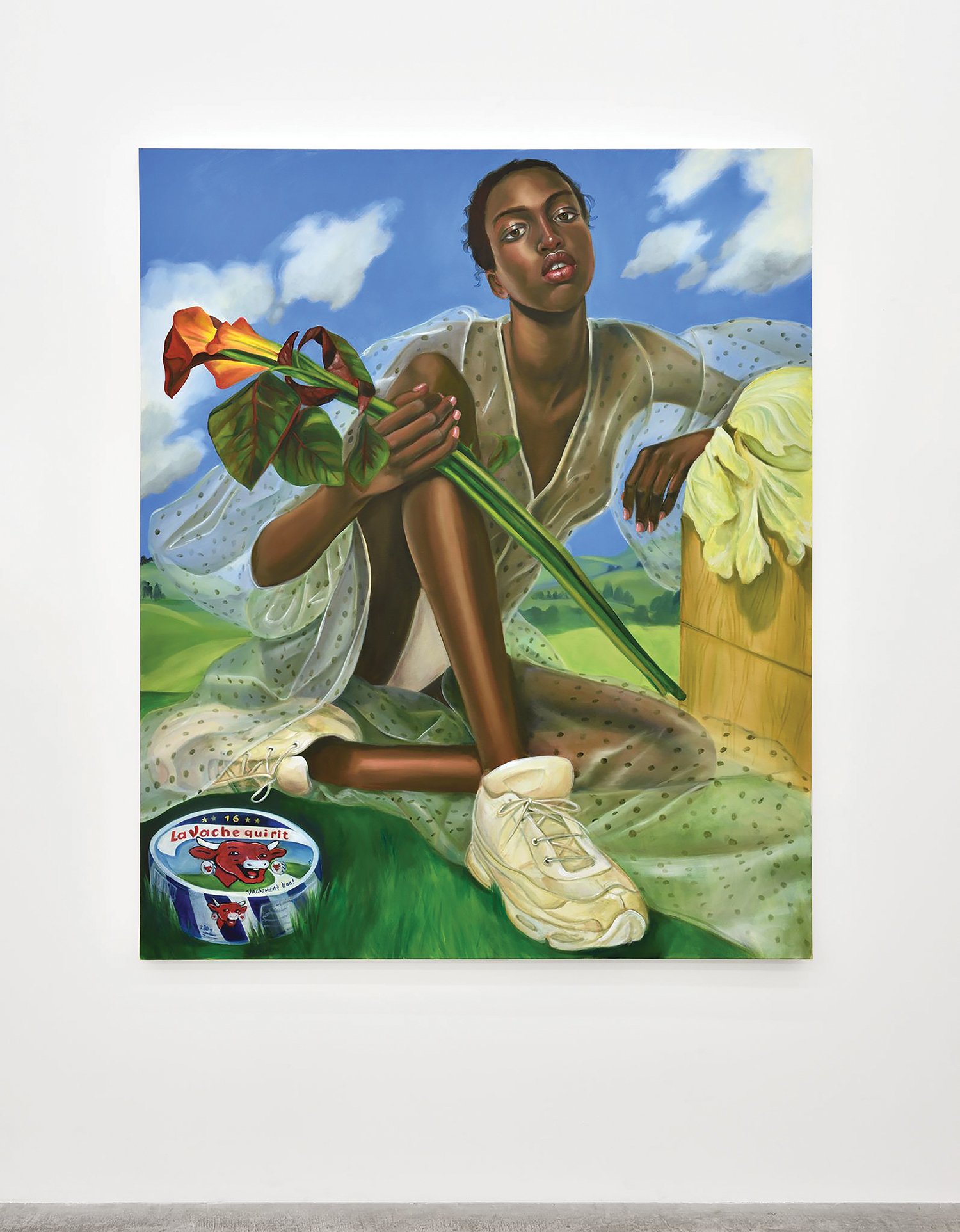

Mary’s a different character for me. I played a killer before, but she was an ex-army sniper. Mary struck a chord in me because she’s a woman and she is a hired killer. She gets paid to kill. That was interesting to me because that’s usually something men do. We’re emotional creatures; we feel. I wanted to explore that side. The beautiful thing about Mary is you’re meeting her at a crossroad. The audience is meeting her where she wants something else for her life. She has never felt maternal, and all of a sudden she meets this kid through whom she sees herself. She sees a chance to not only save herself, but save this kid from the same life she’s had.

Mary was an orphan and she was found by Danny Glover’s character who is a big mob boss. She just was, instinctively, a good killer. I think people are going to want to see this movie because Mary is different, they’ve never seen a serious female black killer. She is a real, straight up, all-about-her-business hit woman. It’s not funny, it’s not jokey, there is no wink-wink on the side. It is very serious, like when you see Liam Neeson or Tom Cruise. You’ve seen white women do it on this level, but you have never seen a black woman in this light.

No, because black women have been so invisible, but not now, not today. I hear you like to take on roles that scare you, why is that?

I know right away that it’s going to be a challenge. I don’t want anything easy. Those are the roles I look for because, in those roles, I will grow. That means it’s going to stretch me. That means, Oh I’ve never done this before. I’ve never tapped into this emotional shit, how do I get there? Proud Mary scared the hell out of me. I’ve never done action before in my life. I wasn’t used to being as physical. If I had it all to do again, I wish we had had more time to train. The great thing about it is, we did reshoot to make it even better because that’s how much the studio believes in this film. I worked seven days a week like a crazy woman to get it right. When we went back to reshoot, the stunt coordinator was really blown away. He was like, I can’t believe you caught on that fast, and I was like, Imagine if we had three weeks to train!

Jumpsuit by Dundas, Boa by Helmut Lang, Earring by Erickson Beamon, Shoes by Aquazzura

Clothing and Shoes by Alexander Wang

What was the research you had to do to play a character who kills?

I came across this guy called The Iceman and I can’t let him go. He was a very handsome man. I forget where he operated out of… New York maybe? But what I found so interesting about him was that he had a family. This man had a family! He had two beautiful daughters and a wife, and he was a hitman. He would go home to his family and they did not know what he did. Finally, he got caught.

I watched his interviews to research the role and psychology. There was a charm about him. He was dangerously charming, and I found myself thinking he was handsome…this is a man who kills people. So, then I thought, Wow, what do you turn on and off inside you to just go out and kill people, and then go back home to your family like nothing ever happened? But Mary is a woman, so how do I make this make sense? Is she void of her feelings and then all of a sudden it changes? It was just a lot of things that I had to explore, and I think after awhile it just became too much, too much blood on her hands. Where is my retirement? You know? When do I get to kick up and get my pedicure, my manicure and live a normal life? You know, everybody wants to retire at some point; I don’t care what you do.

Were there any challenging stunts?

I was shooting a MP5 rifle and you have to smack the trigger to make it look cool on camera. They kept saying, Karate chop it. Well, thank you because now I have blood blisters on my hands! I threw my shoulder out when I had to do this stunt where I had to swing that rifle around with one arm. That’s a heavy rifle! In another stunt, I had to throw a guy over my back. I bit my lip. I got smacked in the head with the magazine of my partner’s rifle. I have bruises. These are the things people don’t realize when they see it on the screen, it’s, Oh that was incredible! No one really understands that you’re risking your life in it. If you’re tired, if you’re fatigued, you make the wrong step, you could really hurt yourself.

Oh yes, I’ve gotten many bruises and scrapes too. Often people couldn’t believe I was a lead that held a gun, that I played a character that could actually take a life and defend my family and myself. They were so shocked, and that realm created the audience for a woman in action films.

Now, I know you’re about to star in the upcoming movie, Best of Enemies. Tell me about playing the real life civil rights leader, Ann Atwater, and her association with the leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

This movie is about how love can conquer hate. Ann Atwater was a poor woman; so was Claiborne Paul Ellis, the Ku Klux Klan character that Sam Rockwell plays. They were both poor, living in a poor neighborhood. The school where the black children attended burned down, so the children had to integrate into the white school. Well, of course, the white people of the town had an issue with that because there was a heavy Ku Klux Klan influence. The councilmen and a lawyer from the North had to step in to come to some kind of agreement for these kids.

Through this process, things were very hateful and scary. People’s lives were threatened. It wasn’t easy back then trying to mix the races, but Ann was boisterous; she didn’t care. She spent her entire life in poverty, but she fought for those people just like her. She was very loud about it; you could hear her before you see her. So, she and Claiborne developed a friendship through this tumultuous time and he ended up denouncing the KKK. They were the best of friends; their story is beautiful and I can’t wait until it comes out.

To play Ann Atwater, I had to totally change the way I look. I wore a fat-suit because we don’t look anything alike. I remember the paparazzi came on set one day. They saw a light skin woman with hair slick and styled, and they thought that was me. But Ann Atwater had a short afro and I had darkened my skin because she’s a little darker. So, they didn’t spot me. So, when it came out in the local newspaper, that Taraji P. Henson was in town filming her movie, the picture wasn’t of me and I was so happy because I didn’t want those images floating around yet. It would have been like they kind of gave us away before the movie poster had been released. You’re not going to believe who you’re looking at when you see me.

That’s a part of our craft that we so cherish, our transformations into our characters. I gained weight for mine, cut my hair, shaved off my eyebrows, but it’s part of the work. You want to become that character because you’re not going to be able to redo it or reshoot it, and it’s going into the future. Oh, a historical political story of love, I can’t wait for that one! Do you have a motto or philosophy that you live your life by?

Treat others the way that you will have them treat you. It’s got me a long way in life. You are kind to me, I’ll be kind to you because that’s what I want from you.

There you go! I guess most people attempt to live their life by how they treat someone because it comes back to you.

It’s called karma, and I believe in it. I have great karma around me because I give good karma. I’m just love, love, love.

And you know what, when you have great karma, great roles come to you, great people, great situations, because I do believe in the law of attraction.

Absolutely, me too.

You know, recently there has been a lot of press exposing the reality of treatment of women in Hollywood/entertainment. Tell me about your thoughts on women supporting women in the industry.

Well, I’ve always been a big supporter of women, even before I got into the industry. I just think overall that that needs to be the narrative. Not just in the industry, but in the world, because art imitates life. If we’re artists, then we need to be setting examples for the world. That’s how I was raised, that’s all I know.

My mother was one of five sisters, so I grew up watching sisterhood. I’m real tight with all of my cousins. We never snitched on each other. We all got in trouble together, and we all went down together. We learned that from our mothers, watching them and how close they are. So, of course I’m going to be like that with other women. I don’t understand hating another woman.

We go through so much as women. Why am I, another woman, going to add to the stresses that women already have? Why would I do that?

Yeah, why tear each other down competitively? We should be supporting each other as women.

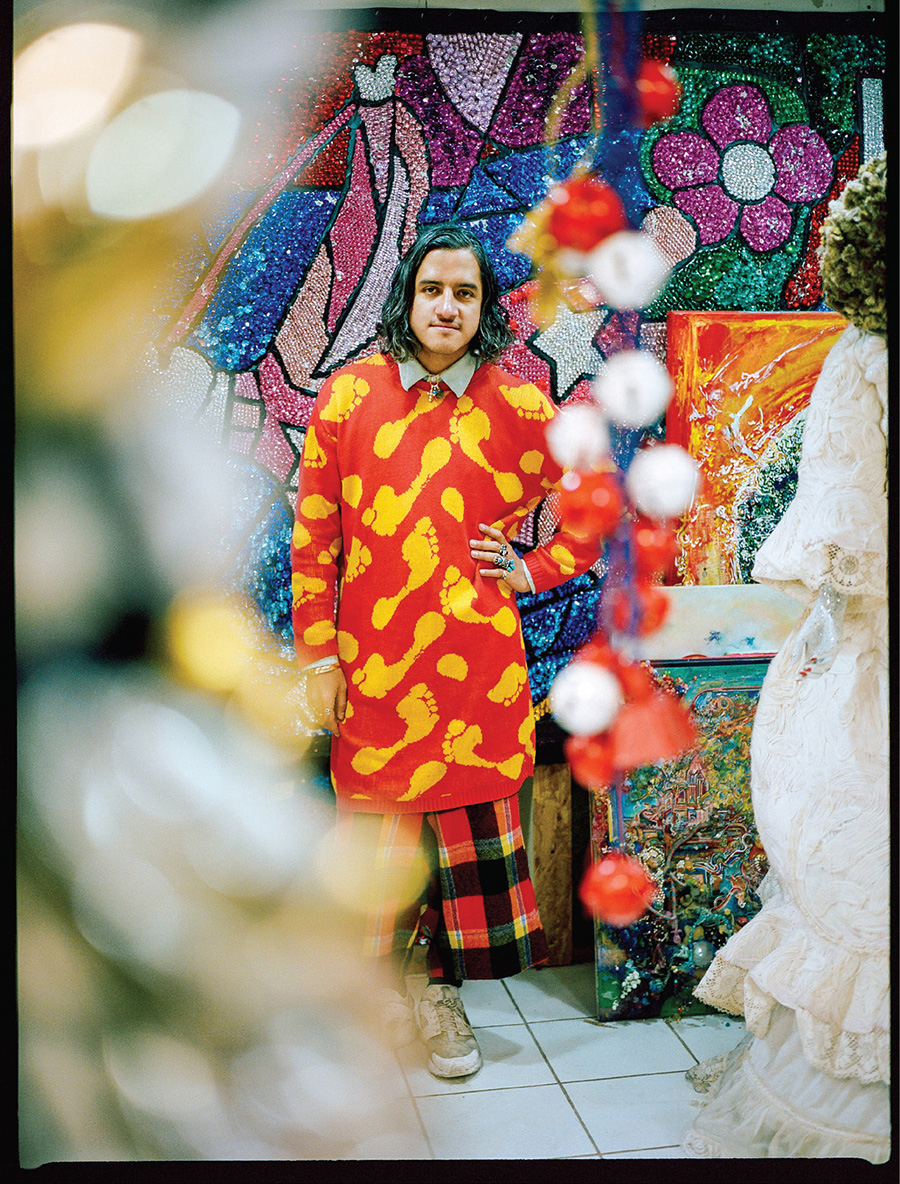

Yeah, why would you want to be that selfish? God didn’t make you the only human. He certainly didn’t make you the only female and he certainly didn’t make you the only female actor. How can I learn if I don’t have my counterpart’s work to watch? You know what I mean? I’m so happy with what’s happening right now in the industry. All of my friends are working. All of them.

Yes, and working at various levels, not only as actors but, you know, writers, producers, directors, costume designers. It’s all across the board in so many ways, and each door that they open, 100 follow.

That’s true.

What advice would you give to young women coming to Hollywood?

Be very clear and know why you’re coming to Hollywood. Whatever that dream is, don’t let anyone deter you. Keep focused on your bigger picture, stay in your lane, do not compare yourself, put in the work, do unto others as you would have them do unto you, and don’t take no shit!

Absolutely! Don’t take no shit!

Jacket, Bodysuit, and Skirt Vintage Gianni Versace at My Haute Wardrobe, Tights by Wolford, Shoes by Christian Louboutin

Hair by Tym Wallace @ Master Mind Artist Management, Makeup by Ashunta Sheriff @ The Montgomery Group for Ashunta Sheriff Beauty, Manicure by Honey @ Exposure NY using Debrorah Lippman, BTS Video DP Francis Chen, Photography Assistants Diego Bendezu and Casanova Cabrera, Stylist Assistant Clair Tang, Production Assistant Benjamin Price, Special Thanks to The Plaza Hotel and Pamela Sharp of Sharp & Associates.

Coat by

Coat by