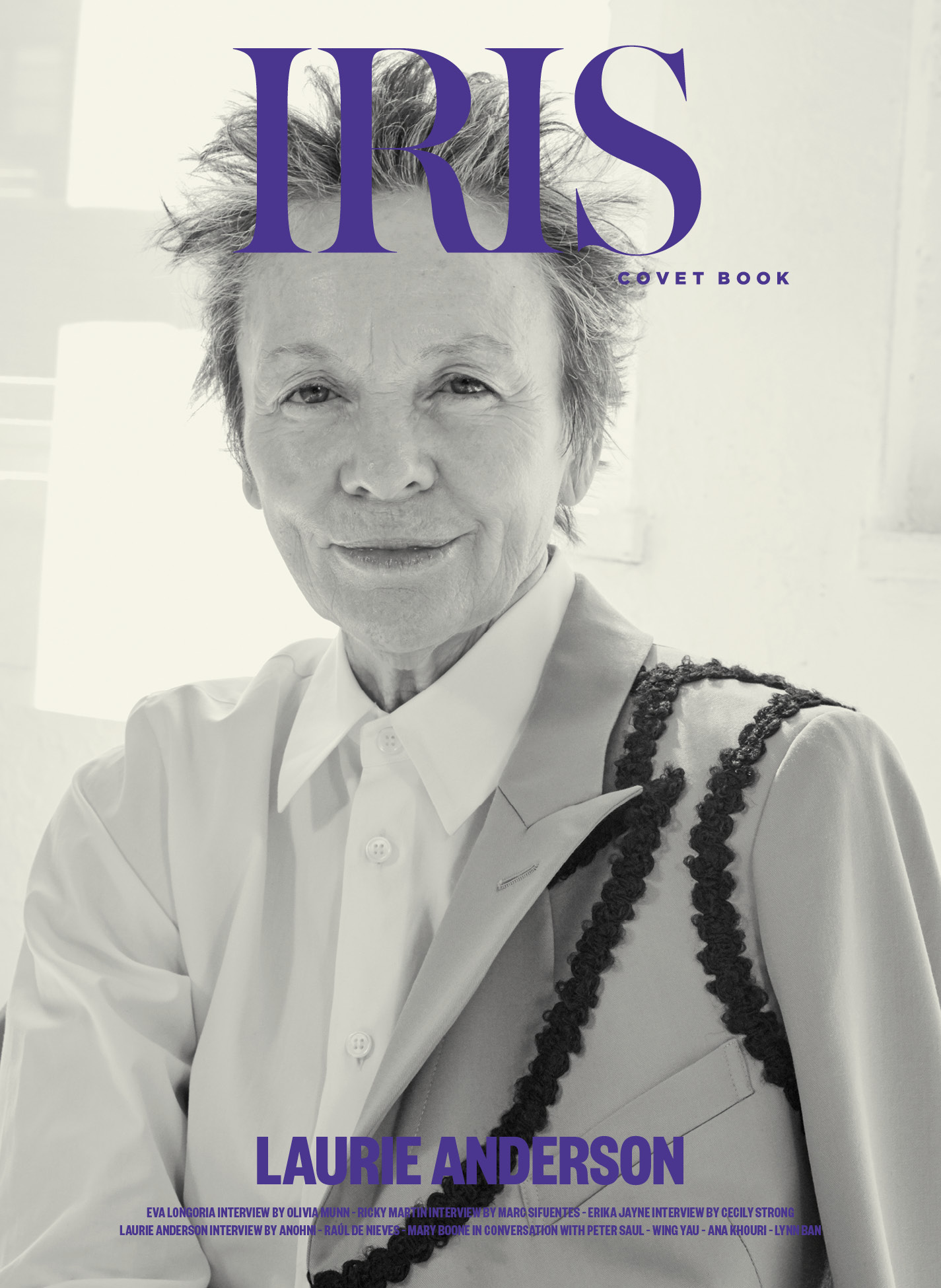

EXCLUSIVE: LAURIE ANDERSON BY ANOHNI

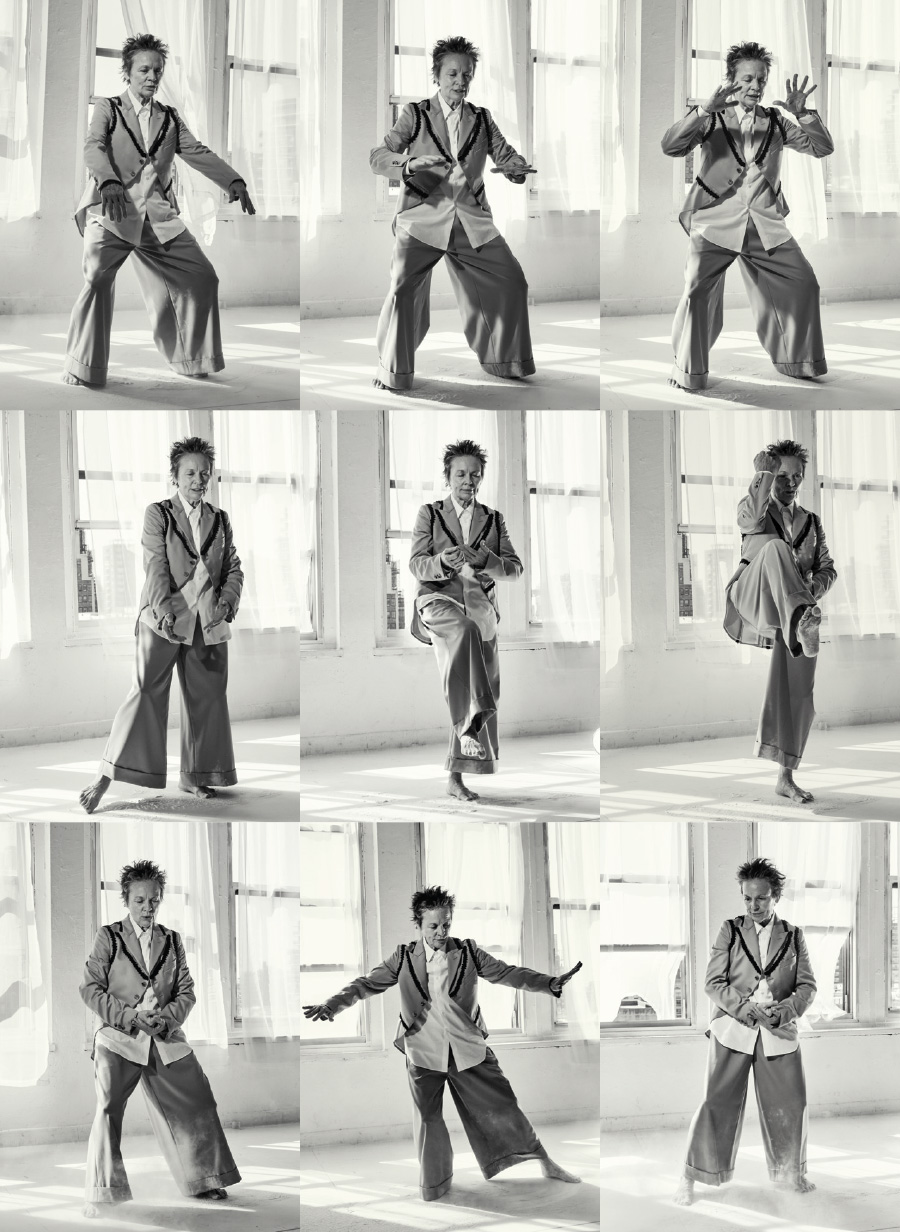

Shirt and Jacket by Comme des Garçons Comme des Garçons

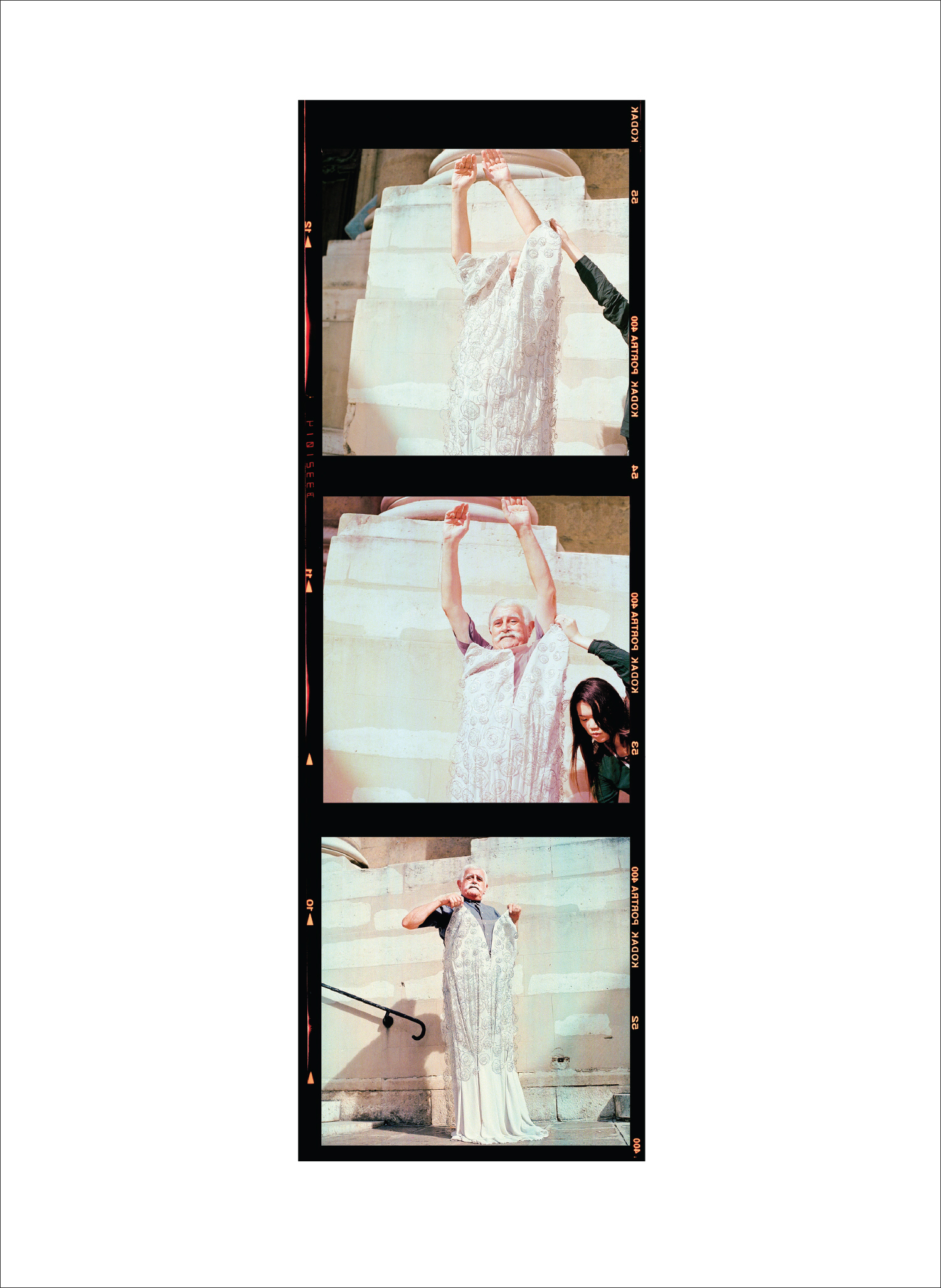

Photography by Jason Rodgers | Styling by Shala Rothenberg | Interview by Anohni

Famed artist, musician, director, and visual/sonic pioneer Laurie Anderson releases a new book and discusses her decades-long career with other-worldly talent Anohni.

Laurie Anderson’s retrospective book, All the Things I Lost in the Flood published by Rizzoli, chronicles her lengthy career in the world of art and music, marriage and collaborative career with the inimitable Lou Reed, and the power of books and language. Anderson’s artistry encompasses composing music, performance art, fiction writing, and filmmaking. A true polymath, her interest in new media made her an early pioneer of harnessing technology for artistic purposes long before the tech boom. Two years ago Anderson began looking through her archive of nearly forty years of work, which includes scores of documentation, notebooks, and sketchbooks.

In this exclusive interview for Iris Covet Book, Anderson speaks with a fellow pioneer. singer, composer, and visual artist Anohni, about art, VR (Virtual Reality), American culture, and the edge.

Hi Laurie, shall we begin? Going back and looking at the accumulated works of your long career, how did working on this book cast new light on your life’s work?

It cast a lot of light! I thought I was doing new projects one after another. As it turns out, I’m doing the same ideas. I can’t believe it. It wasn’t like psychoanalysis, but it was something close to it. I found a lot of things that were really shallow, too, that I put in the book anyway because I had thought at the time, as a young artist, that they were what art was about.

We’re working on a book of Lou’s early poems called Do Angels Need Haircuts? There was one night in 1972 on St. Mark’s, he was reading his poems, and I realized that I was a couple of blocks away that night with my friend Lucy Lippard, the art critic. We talked endlessly about ‘the edge.’ That was really important to us. We’ve done too many images, too many colors and too many lines. What art is about now is how we see things. That’s what we felt. We were making things that called attention to the fact that we were paying attention. So this all was very meaningful at the time. You could write long, long essays on ‘the edge’, the edge between this reality and the other.

For me, it meant doing minimal sculptures. I was making things. And they looked pretty much like something you would see at any construction site, a piece of sheetrock leaning against a wall, or a line bisecting the room. And that’s what we talked about and that’s what gave meaning to our work. Now if you try to talk about that now, people don’t have the slightest idea what you’re talking about.

Was that conversation a foundation for what we’re talking about now? In terms of seeing multiple points of view? Intersectional thinking, spectral thinking… you were pioneering that.

John Cage was pioneering it when he said, “Everything is music.” Robert Morris was pioneering it when he said this cube is a work of art, this plywood cube, because it forces you to look at the edge and your displacement and your position versus it. It forces you to use your eyes.

Eventually I began to use images again, and I thought, “Am I going backwards?” But then I wasn’t bothered by it anymore. I no longer see my life as progress. I just see it as trying different things at different times. One art form isn’t truly more advanced than the other. I just came from a conversation about how sound works in virtual reality. How can you make music and sound that doesn’t have a beginning and an end? What does that stuff look like? That’s the way we’ve always made music through history… with a beginning, a middle, and an end. But our lives don’t work that way so much either. Mine doesn’t have a beginning, middle and an end. I was born at one point and I’ll die at one point. The stories of our lives just don’t have any plots. Mine doesn’t really have a plot.

The only thing I’m pretty sure of is that we are evolving towards complexity. We are not sliding back down the evolutionary scale, slowly becoming toads and single cell creatures.

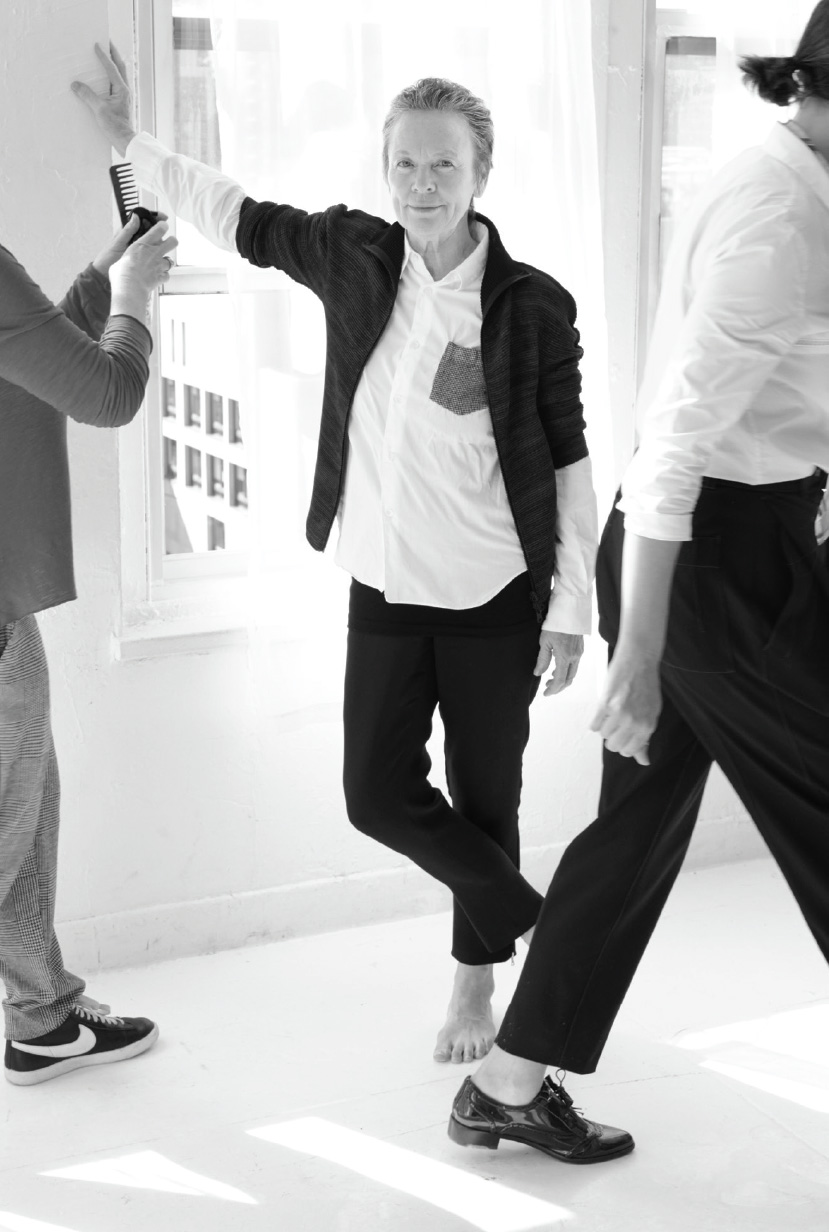

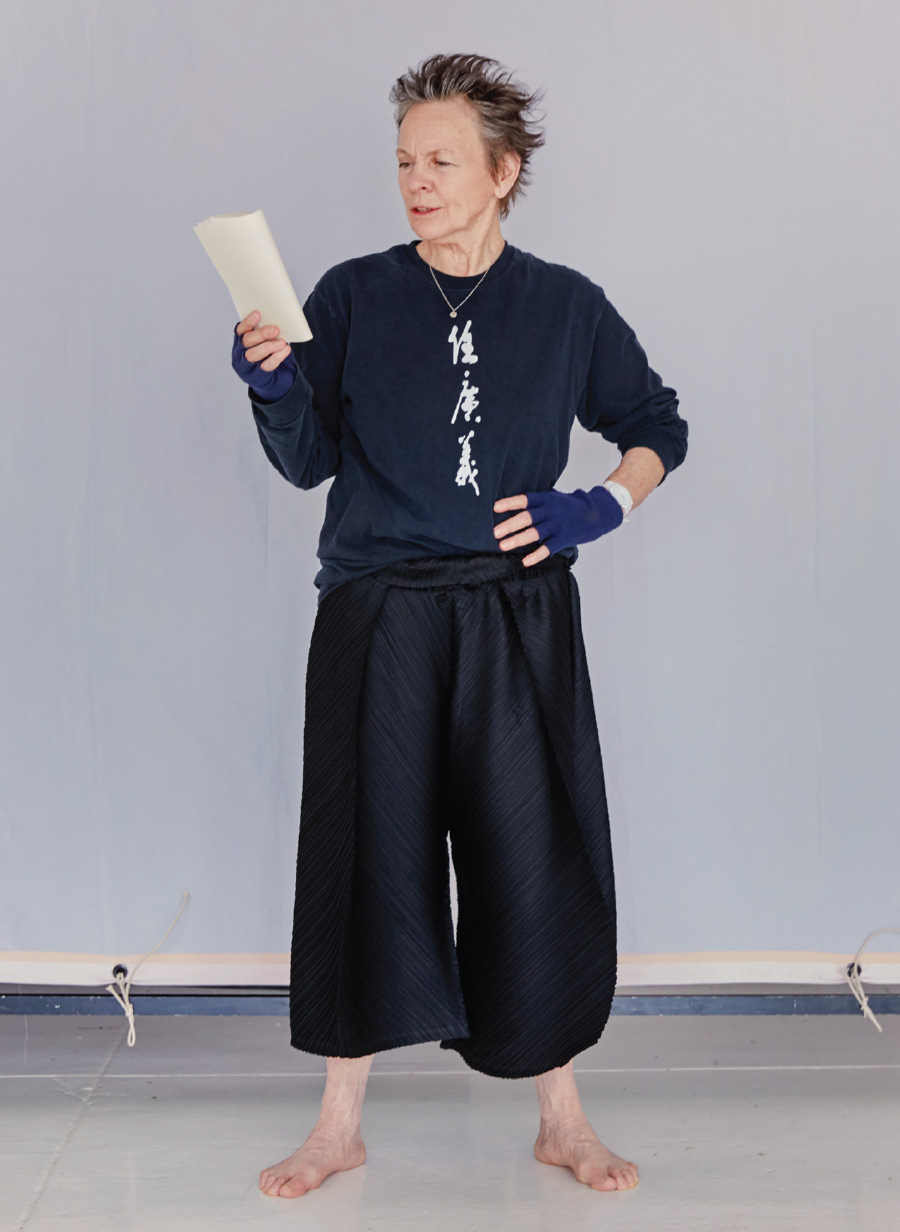

Jacket by Issey Miyake, Shirt by Comme des Garçons, and Laurie’s own Morgan Le Fay Trousers.

Shirt by Comme des Garçons, and Laurie’s own Morgan Le Fay Trousers.

The series of drawings you did about the life and death of your terrier Lolabelle in the film you created Heart of a Dog are so beautifully illustrated. There was a strong sense of the space itself in those drawings, supporting the figures and objects. I loved that you brought the aesthetic of your hand drawings into VR. It’s markedly different from every other experience of VR that I’ve had.

It’s because it has dust in it and smudges, and also because we made the atmosphere out of tiny little letters, so you would be able to see the air. It was full of infinitely small, dust mote letters. Most VR is airless. It’s like going into this really sterile boardroom. Like there’s no atmosphere whatsoever.

In the new book, you refer to your work as a combination of narrative and visual language. How have your stories changed over time? What stories are you interested in telling today?

They haven’t changed that much. That’s another thing I realized. I’m a short story teller, and a short story can be a two-sentence story. And if you can get it done in two sentences, then just do that, because who has time?

It’s vivid, and our mind can wrap around it without moving through much time. I think it’s harder for 21st century people now to read, to sit down with Crime and Punishment and absorb all those atmospheres, all those characters, all those days, all those roads, and all those moods, stringing them together. We’re more visual than that now.

You were saying to me recently that you feel like film will soon be relegated to museums… and the future of popular storytelling will be in VR.

VR and MR.

What’s MR?

Mixed reality. I don’t know how to do MR, but I’m really interested in learning. These are lighter weight viewing devices, and of course everything will get lighter until there’s no weight to it at all and it’ll just be retinal. In MR you will have a glass on this table, exactly like this real glass, with the reflections from your computer and of your shirt in there, and it will move, but it won’t be there. It’ll be a virtual glass that is beyond real.

It’s really wonderful for disembodiment, which has always been my personal goal as an artist. To have no body, to fall into a work of art and not be able to get out, ever. Just fall into it. And you can fall into a book, too, identifying so much with the character.

You mentioned in the introduction that the book is about language in live performances, the difference between spoken and written words, the influence of the audience, the use of the first, second and third person voices, metaphor, politics, the story of dreams, songs, misunderstandings and the new meanings that are created when languages are translated. How do you think language can change the world?

I think it might be one of the only things that can change the world, that can really let you see it in another light. Like the wall we’re building between the U.S. and Mexico. It’s actually not a wall. The wall doesn’t exist yet, but the wall is so real in our minds and it’s such a contentious thing that it’s more than real. And you have to remember, the wall is just somebody’s idea. It’s a wall of words. People react to it as if it were a real wall. We’re already living in a virtual world, you know? It’s not there yet. We haven’t even collected the money to build it. So you have to remind yourself that we live in a fantasy world, a dream world, where half the things that we’re talking about don’t actually exist.

I think it’s supported by contemporary technologies and media. It’s almost a tenet of fascist propaganda, that if you say something five times it becomes real. And I think that’s very much what Trump did with the wall. He said it so often that it became a specter in our minds and imaginations. And that leads me to a question about mythology and storytelling. Do we have a moral responsibility to write other stories besides the ones that seem most likely to happen?

I think we have a moral imperative to tell stories that turn out better than we think they might.

Last December, the Sag Harbor Theater burned down. They asked a bunch of people to pick the film that they think best embodies American values. I picked American Psycho, and we screened it on Sunday. It was a little beyond the veil for people in South Hampton. Even after the Valentine’s Day massacre, they don’t want to tell the story of a white psycho-killer who wants to kill people because he just doesn’t have enough stuff. He doesn’t have it the way he wants it. Frankly, I find the most frightening part of that story was the way the guy treated women, the cartoony-ness.

It was really disconcerting. You tell the story that you feel like telling. To me, American Psycho is very representative of what people love in this country: status and beautiful things and power and lording it over other people, and men being these absolute creeps. The prostitution was the thing that bothered me most. That was much more horrifying than the cartoony, meat-chopper stuff. People reacted to the chainsaw stuff because it’s horrible. He grabs a woman’s leg and tries to eat it. But the truly scary stuff were the things that were very real to me, which is the dismissive way that these hedge funders were talking about women, saying, “Have you ever seen an intelligent woman? I haven’t.” But people didn’t see that part of the film, because that’s so much a part of the culture.

Is this kind of storytelling the same thing as myth? In one way, it’s a discourse talking metaphorically about what’s happening. But does it reach even deeper than that?

Think of the Greeks – Medea, Electra…all about hacking the head off your mother and eating the bones. I mean, horror movies are Greek. They’re really Greek. They’re about the hatred and rage we feel towards each other, particularly the rage towards mothers and fathers. So those are our DNA stories. But then you have these stories about heaven and particularly the ones that are trying to convince you to behave in a certain way. I don’t think they’re so much about morality or rules. I think they’re about time, ways to explain time to people, where you came from. Where are you going to go after you die? You’re going to go to heaven or you’re going to go to Nirvana or you’re going to stay in the cycle of suffering, or you’re going to be with a bunch of virgins. Time is the biggest mystery to us.

When the Christians concocted the ascent to heaven and the final coming and fire and brimstone, that was all a projection into the future.

I think it’s not very clear, because they disguised a story as something that is about human personality, and then distorted it to punish people for being bad people, because that’s the other important part of the myth. There’s something very wrong with you, and you were born with something wrong with you, and you’re going to be punished unless you do this. And that gets various shadings, like the King James Bible, for example. Jesus had always been in the Christian Bible referred to as Master or Teacher. King James wrote his Bible, and he paid for this Bible. It was the first time Jesus was called King of Kings, Lord of Lords. He became a secular, powerful person, not a teacher.

So everyone is using these structures and these stories for their own ends to get what they want, particularly power. That’s what religion mostly has come down to. It’s about control.

Shirt, Jacket and Trousers by Comme des Garçons Comme des Garçons

Shirt, Jacket and Trousers by Comme des Garçons Comme des Garçons

Did it work? Did they get that control through the use of story? Or did the story tell of the power that they had already acquired? Is there a power in storytelling that can define the future, or even form the future?

Sure. That’s why I think women telling different stories is fantastic. Even in American Psycho, some of the greatest shots were the reaction shots of the women. Everyone is focusing on the men. But these cameras pan over to the women and they’re going, “What? Can you believe this asshole?” They’re not saying anything, but you can see it, it’s fantastic. This silent language of this woman filmmaker is telling a very different story. She’s telling it on a bunch of different levels. It’s a really complicated film.

Today, marginalized groups are sharing their narratives to ever increasing and attentive audiences. How has this recent cultural phenomena affected your work and your outlook on the work you’ve done?

When I was a young artist in the early ‘70s, I was part of a group of women artists. I joined it because I thought “OK, finally a group of people are joining together because we have different things to say than men,” and we do. But what was the focus of it? How to get into galleries. And I understand that on a professional level, but that’s not what I was there for. I was trying to find commonality with this group and be part of something.

And this was at the same time as separatist inclinations in various self-advocacy groups nationally. But you’re sort of describing a scene downtown that was more utopian.

I hope I’m not painting it as something it wasn’t, but I have some great memories of how much we did help each other. We saw ourselves as workers, somehow. That was the main thing. There were a lot of things that had opened people up in ways that were pretty wild. A lot of drugs around, a lot of sex, a lot of fun. Helping each other on every level. As soon as money came into it, things changed. We never thought we would make a dime from our work. That was the furthest thing from our minds. We all had little jobs, and you didn’t need that much money either. That’s another very important point. You needed almost nothing. You didn’t think about it.

I’m thinking about a photo of you in the book, standing in a crowd playing the violin. You’re talking about not really aspiring to get into galleries, as much, and there you were sort of just outdoors being scrutinized by these gangs of passersby. That image just reminded me of some of the stories you’ve told me of things you’ve done over the years, hitchhiking to the North Pole, just being out there in the wind.

Yeah. I did always want to get out, that’s for sure. I wanted to be part of an art world. But not one that was chummy, more that was supportive. So I was lucky enough to hit that NYC wave at the right moment.

For young artists, where do we go from there? How do we move forward?

To a young artist today, I would say “Don’t listen to me.” That would be number one. Each person finds it for themselves, and that’s the whole great thing about this. No one can tell you what it is. It’s your responsibility to find it. We have a million roads out from here, as many roads as there are artists to follow them. So question all sorts of things, even the idea of progress itself. One of the things I’m interested in, as you are as well, is the ends of stories and what happens. So I asked my meditation teacher, “What happens to karma when there’s no one to embody your karma, and the whole system, the great dharma wheel, crashes?” It’s built on continuity and giant eons of time, the big wheels of time. So when that wheel stops and we’re not on it anymore, what happens? And he said that’s why the Buddha talked about other universes. I just loved that so much. It was so freeing to me.

It’s a kind of independence.

It’s your freedom to go anywhere and to realize that the rules are idiotic. I mean, maybe that’s one thing I would say, is that there are no rules, so don’t worry about that part. There are zero rules. It’s hard to be free.

Pants by Issey Miyake, T-Shirt by Tai Chi, and Laurie’s own gloves and jewelry.

Hair by Elsa Canedo Using Kerastase, Makeup by Kento Utsubo, Photo Assistant Jordan James, Special Thanks to Rizzoli. Laurie Anderson: All the Things I Lost in the Flood, Available on rizzolibookstore.com

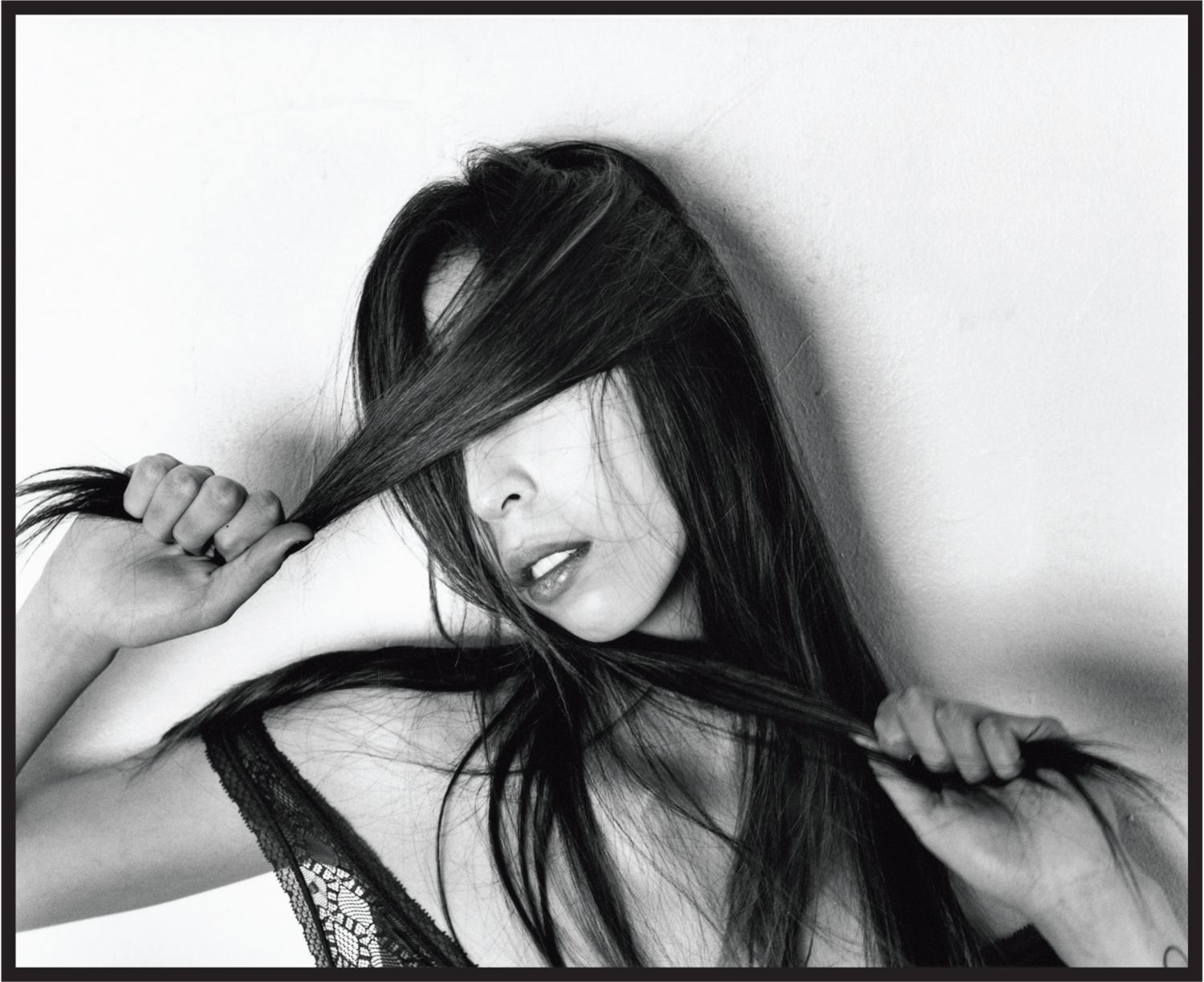

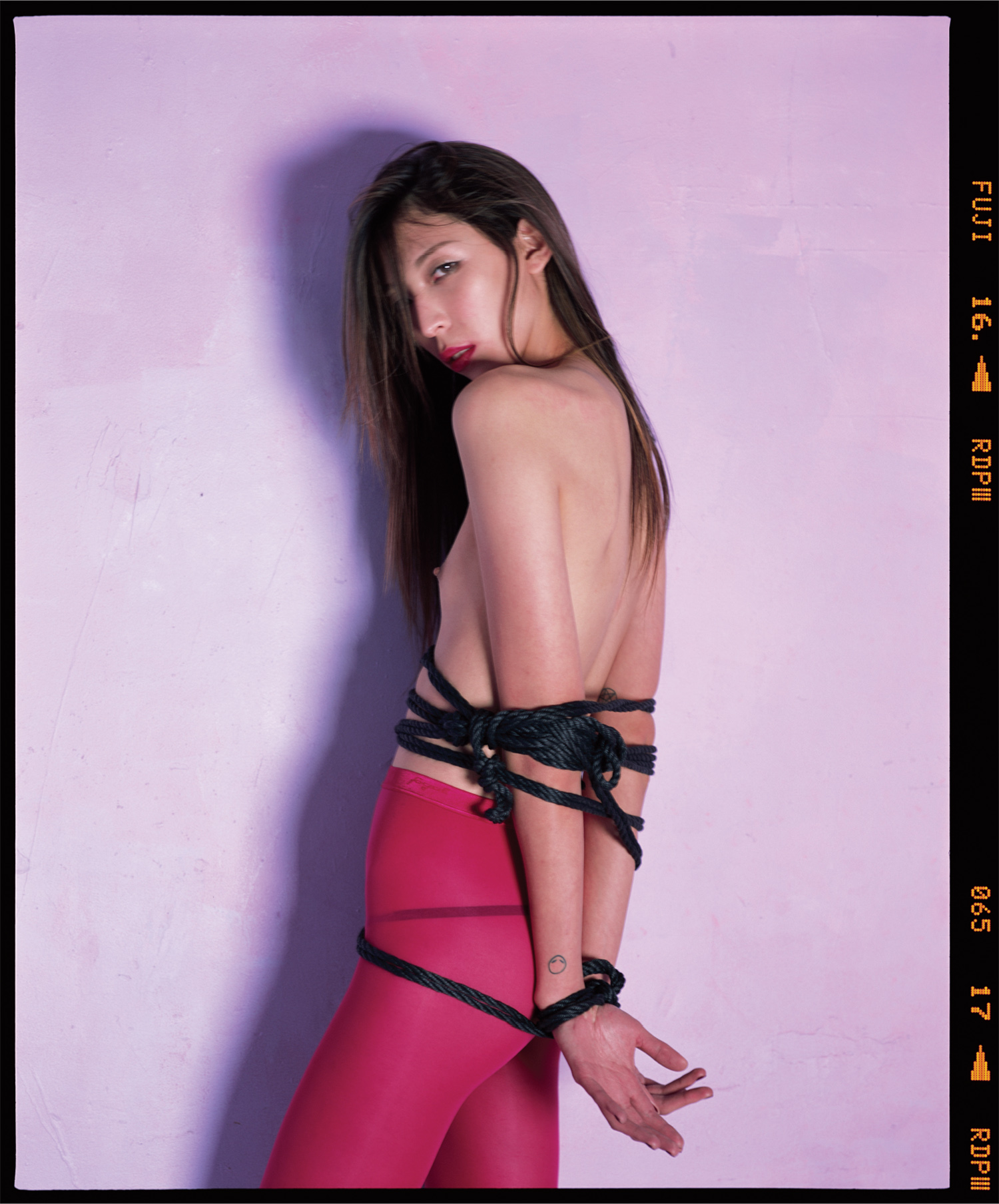

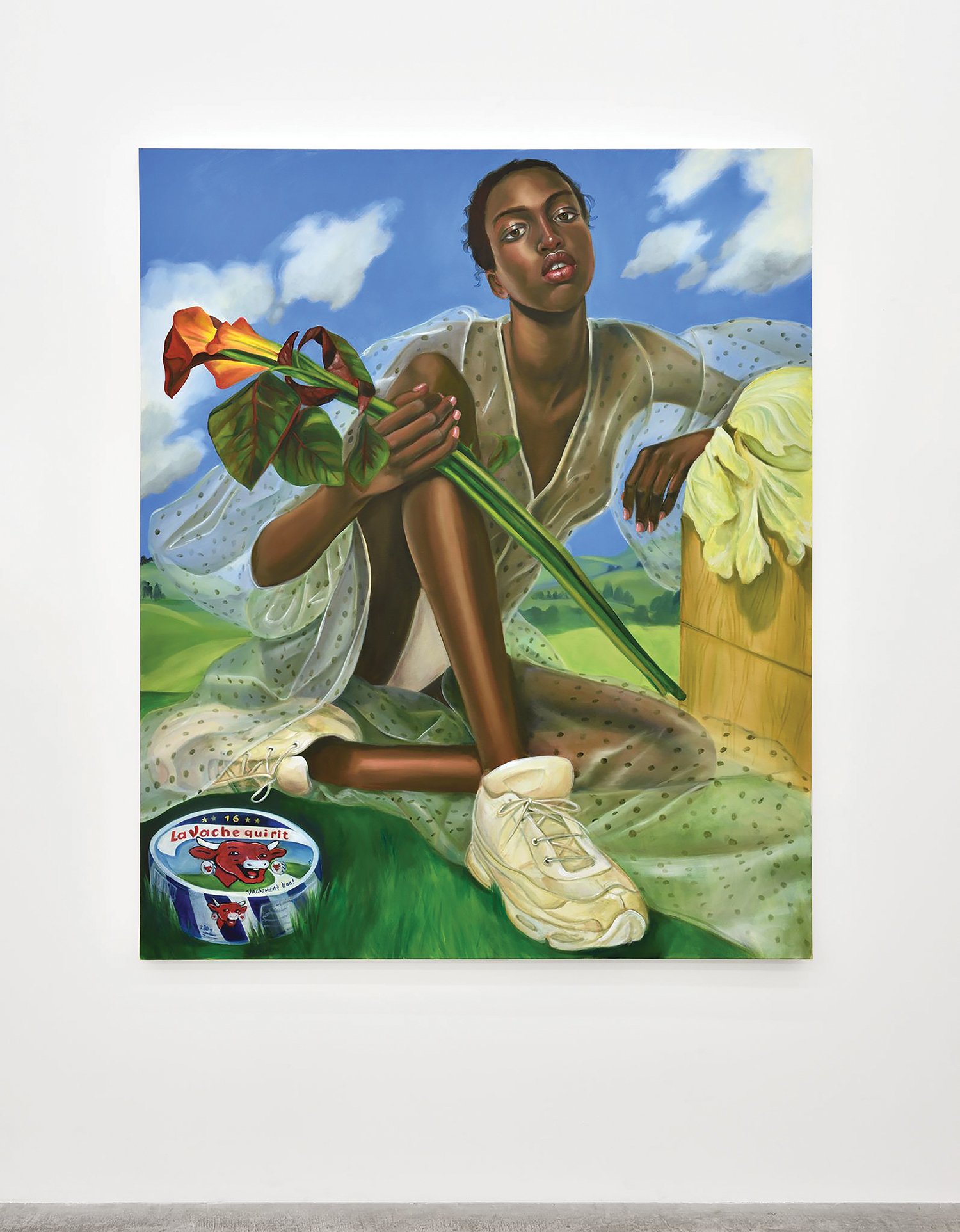

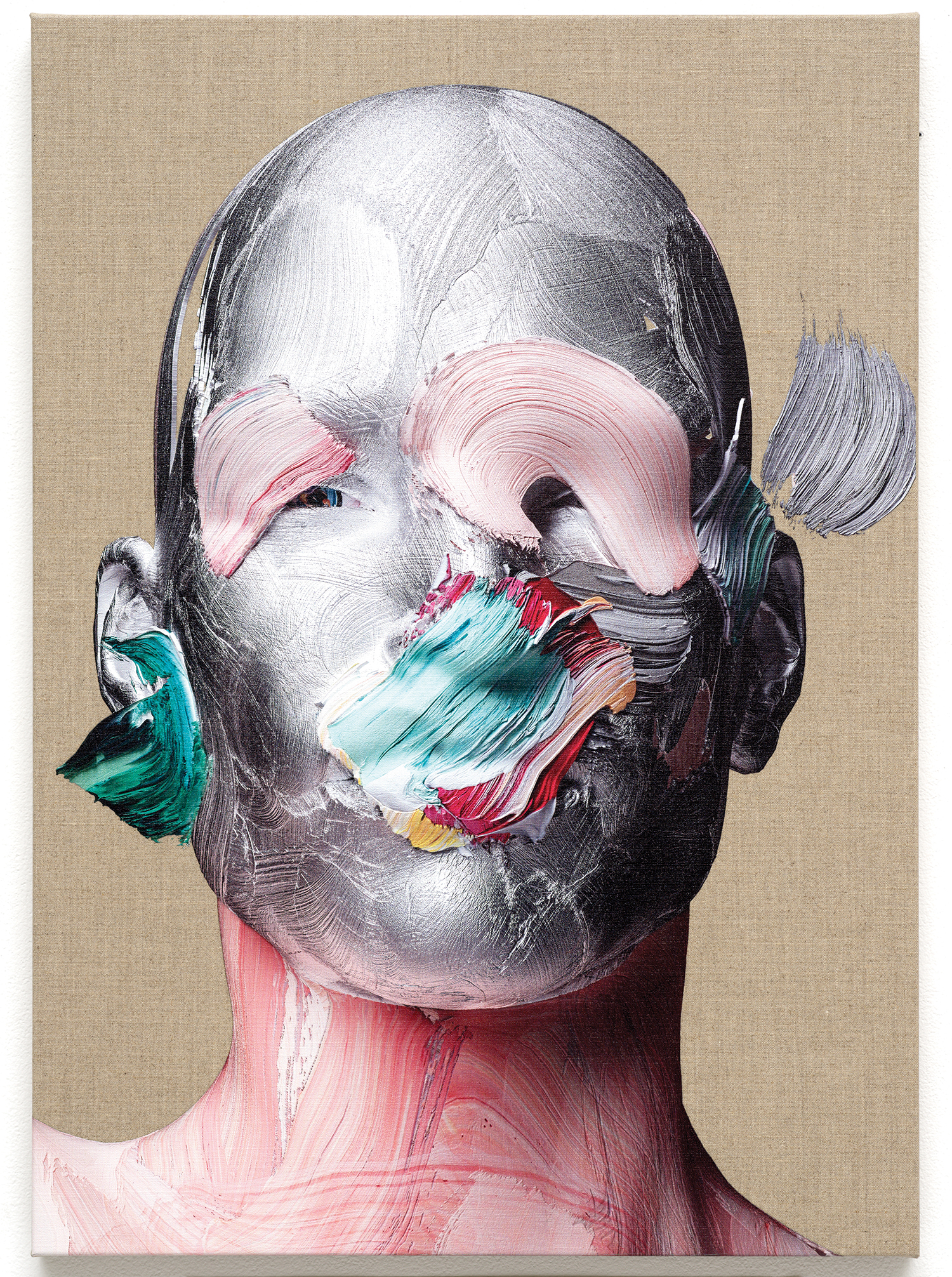

Photography by Nobuyoshi Araki | Styling by Shun Watanabe | Model Issa Lish @ Women Management

Photography by Nobuyoshi Araki | Styling by Shun Watanabe | Model Issa Lish @ Women Management Coat by

Coat by