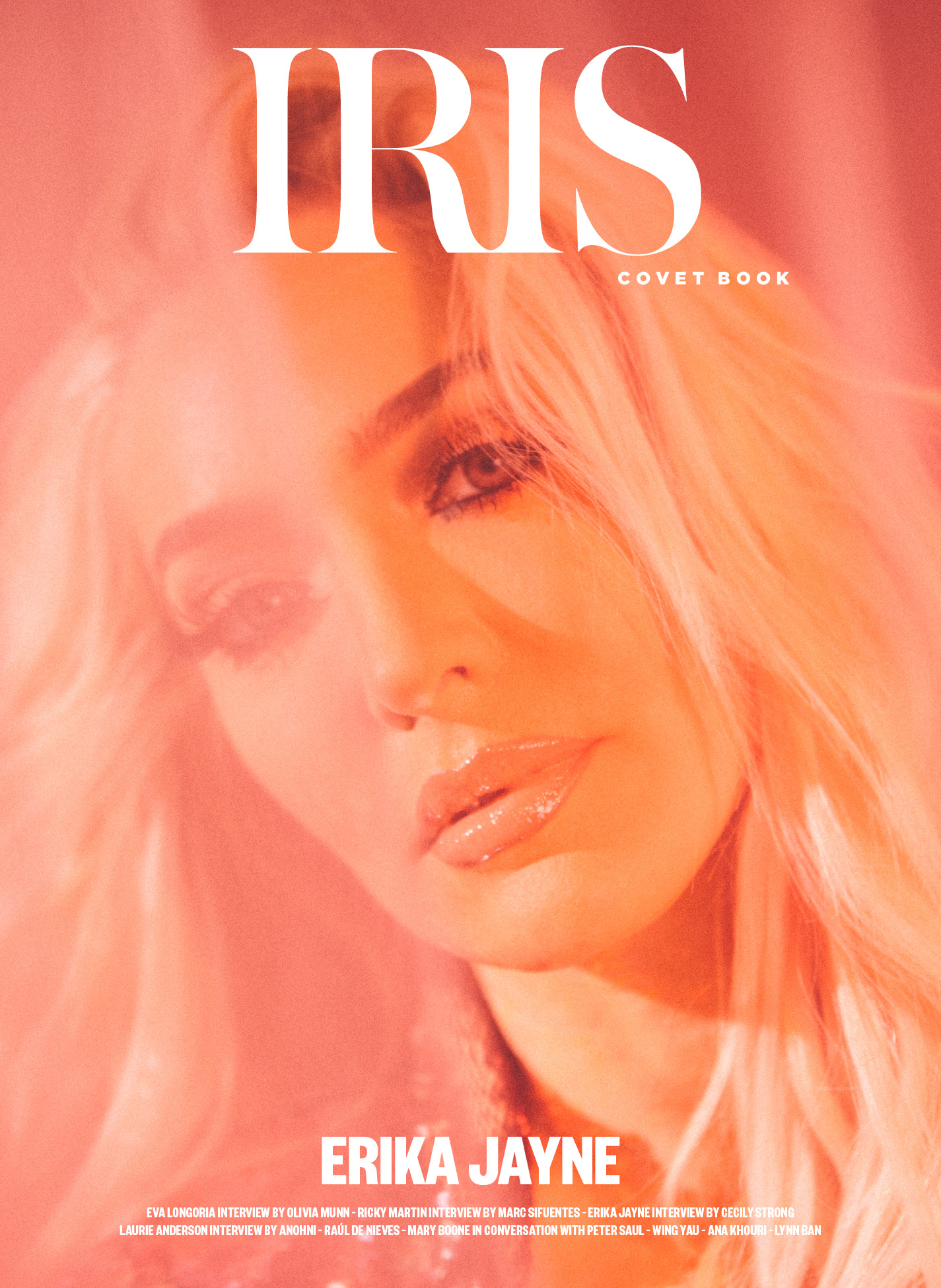

EXCLUSIVE: ERIKA JAYNE

Photography by Alexandra Gavillet | Styling by Rafael Linares @ Art Department | Interview by Cecily Strong

From dancing on gin-soaked stages in the dive bars of West Hollywood, navigating the many dramas of the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, to being immortally satirized on Saturday Night Live, the reality star, pop culture icon, and now New York Times best-selling author is taking the world by storm.

Erika Jayne is embracing opportunities with open arms, switching at the drop of a hat between author, international performer, “housewife,” and the icon we didn’t even know we needed. The Real Housewives franchises are filled with meme-worthy moments, unforgettable quotes, and exciting drama, but few women from the reality series have become household names to the degree of Erika Girardi, AKA Erika Jayne. In an exclusive interview between Erika and Saturday Night Live’s Cecily Strong, who parodied Jayne on the legendary sketch show and cemented Erika’s status as a cultural touchstone, the two women discuss ageism in the entertainment industry, creating a public persona, and her new Simon & Schuster bestselling book, Pretty Mess.

Jacket by Tom Ford, Earrings by House of Emmanuele

Earrings by House of Emmanuele

Hello! How are you Erika?

Hi Cecily, I am so goodit’s so nice to talk to you.

You too, what a treat! I am such a fan! A real fan, not just an Instagram fan. I am so excited. I’ve been bragging to everyone at SNL about getting to do this interview! So, starting with your new book, how did the idea to publish a memoir take off?

I was approached to do the book and said yes because these days I am just saying yes to everything. Obviously, you see a little bit of it on TV, but sharing 45 minutes of screen time with five other women is difficult. Writing a memoir is a way to give the audience a more in-depth peek into my life.

How open are you in this book and are you nervous about revealing too much?

There’s always the version of the truth which you can never tell or else all of your friends and family will never talk to you again (laughs), and then there is the book that I wrote, and then there is the book that got published – which went through two legal processes. Hopefully it works out well and people like it.

(laughs) What was the most challenging part writing the book?

Well, my mother and I were discussing how my father left when I was nine months old, and then she remarried and divorced again. I feel like I had blocked out that part of my childhood. I went back with her trying to piece it all back together. I was looking at it through 46 year-old eyes and thinking it was basically ten years of bullshit!

Do you think that your childhood experiences are the reason that you have this amazing life and personality and are so fabulous and youthful—or in other words, do you think that you’re basking in the things you didn’t have in your childhood?

I feel like I’m eternally 16. I had a nice car, a hot boyfriend, good grades, was performing all the time, and I looked cute. I don’t know if that’s because of my childhood, but I definitely know that all of that has an effect on you growing up.

Well, I understand feeling like you’re eternally a teenager because I feel like I’m 16 even though I’m like… 34, but have you confronted ageism in your industry? Is it something you even think about? I know I don’t think about it much.

Good, and I’m glad you don’t, and the only time I do is when someone tells me, “Oh, aren’t you a little too old to be doing this?” and I’m like, “No, actually I’m not.” I think that it’s important to keep doing it and keep pushing and dreaming because that’s an old way of thinking that is falling by the wayside as women continue to improve and show how powerful we are. You know, when you’re in your 40’s you’re not dead, you’re not done! I feel the most powerful now. I didn’t feel powerful in my 20’s, I was a ding-dong!

I couldn’t wait to turn 30 because I thought, “Finally, people will take me seriously!” And I can’t imagine someone saying to you that you’re too old, that’s insane to me. I’d be like, “Just watch me perform!”

Thank you! Could you imagine telling a man that? Could you imagine telling a man, “Sir, don’t you think you’re a little too old to be running the company?” It’s not fair for us to get a tap on the shoulder like, “Sit down honey, you’ve had enough fun, you’ve had your day, people don’t find you attractive, you can’t sell anything, and your time is up” No! I’m not going to do that.

Good, me neither. We’re taking a vow! What do you hope that people take away from your book and your personal story?

First off, I want people to laugh and have fun. It’s an easy read and a fun read, and if one person walks away inspired to go to dance class again or back to college or just see that, through this human story, we are all the same. My experience is just this way, but it’s the same bullshit for everybody, so don’t quit. You never know what the future holds.

So let’s talk about your persona Erika Jayne, how she was born and how you found her within yourself?

I was about 35 years old, had been married to Tom for six or seven years, and had been exclusively living his lifestyle. I was going to every event and socializing with a whole new set of very educated, super interesting people. I am glad I did it because it was an invaluable education, but it wasn’t me. I was wealthy and living in a bubble where I would shop, go to the gym, and then go to dinners, but what the fuck was I really doing with myself? I longed to go out, create again, and have my own identity.

I just don’t think that Tom expected the book deal, concerts, or this interview in my future. I don’t think anybody did! I started to create on my own, it was something that I loved, and here we are today. And thank God he has been so supportive. I have learned so much, and I am really grateful because without him I wouldn’t be here at all.

That’s so great, and good for you two! You’re a great example for couples. So, when did you get your big break and what was the beginning of your career as Erika Jayne like?

Well, if you take the Erika Jayne Project, it was very small potatoes. It started at my kitchen table and it was just something that I wanted to do. I created the persona with a friend of mine from high school. He took me to a producer friend of his and we made the Pretty Mess album, and I started to perform because that’s what I really love to do. It was the typical beginning. A few people in some terrible dump, no one paying attention, and just begging to get on stage. I thought to myself, “I don’t have to fucking do this, I’m rich! What the fuck am I doing?” (Cecily laughs) I hate to break it down and sound so rude, but there are a lot of naysayers and rejection. I kept putting one foot in front of the other and building it, and slowly but surely people started to pay more attention and come to my shows. The biggest break into pop culture was definitely being cast in the Real Housewives because it took Erika Jayne out of the clubs and into people’s homes, and she even became a parody on Saturday Night Live! (laughs) But I think the most interesting thing was seeing young women, like high school and college-aged girls tell me how much they love my music and style, and I’m like, “Wow, really? I’m old enough to be your mom.” That acknowledgement makes it all worth it.

Jacket by Vitor Zerbinato, Dress by Nookie, Boots by Christian Louboutin, Earrings and Ring by Glynneth B.

Jacket by Vitor Zerbinato

Most of my circle of friends are gay men, and so I’m curious when did your relationship with the gay community start?

Children’s theater! (laughs)

Oh my God! Same for me! I was raised in a theater in Chicago by a group of gay men.

That was where I started! And then I went to a performing arts high school where everyone in dance and theater was gay, even our instructors were gay. They were always a part of my life. These are my people and that’s that.

Right, it’s so true, and it’s so funny that I had a very similar experience. When my parents split up I felt that the gay men of my Chicago theater were raising me while my family was a mess.

And I think that’s a wonderful thing to have and I can’t imagine life without gay people in it. They are my closest confidants.

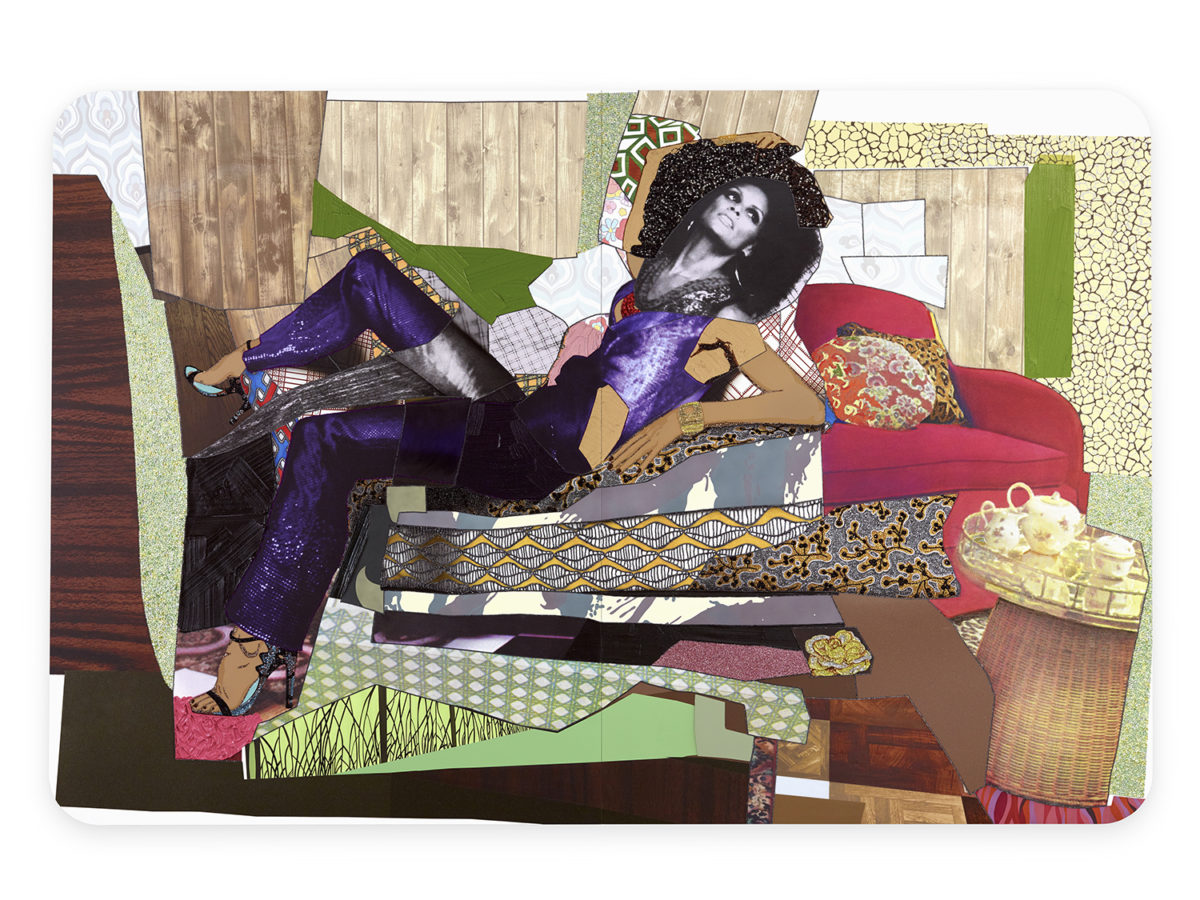

Now what about drag culture? Has drag had an influence on your life and career?

I mean, just take one look at me! What do you think? (laughs) Of course! I love drag because you get to transform into a superhuman. It’s a true art form that is not for the faint of heart. Your costumes, hair, makeup, the whole look, and your style of drag too! There are so many different styles.

What style would you be?

Hooker drag! I want to be hooker drag (both laugh). Are you kidding? Basically that’s what I already am so why not? Keep it going!

So let’s talk Housewives of Beverly Hills! Obviously I am a huge fan, but how has being on the show changed your life? Cameras catching you crying, drunk…I drink a lot, so I could never do reality TV.

I don’t really like crying on camera because you are embarrassed worldwide, and that sucks. But without that exposure I wouldn’t be talking to Cecily Strong and I wouldn’t have a book out today! See what I’m saying? You have to roll with the punches and make the best of it. At the end of the day, it is reality television and I try to be as authentic as I can and have a good time doing it!

As I say in my book, it’s like professional wrestling. There are heroes, villains, costumes, pyrotechnics, but at the end of the day the injuries are real! It’s like we are participating in this absurd narrative, but these are still my feelings and sometimes they get really hurt.

People are awful! Celebrity in general, people feel like they have some sort of ownership over you, and because you get to do your job they get to hurl insults at you. It seems even worse for people in reality TV because it is your name and your life.

Thank god I am 46 and not 26! I have lived a full life, have a successful marriage, had an unsuccessful marriage, I have an adult child, I can pay the bills. Forget it, if I were a kid and did not know who I was, I may not have made it and I would have been crazy-town. Honestly, I consider myself pretty fucking normal.

I think about that all the time. Like I was crazy enough at 22—

Right! I didn’t need anyone telling me I sucked and was awful and should kill myself. You can imagine how the younger ones feel.

I will say that my favorite piece of advice I’ve ever gotten, and I don’t mean to name drop, but it was from Jim Carey at a host dinner for SNL and he told me “Don’t ever let anyone tell you the narrative of your career.”

He’s right, and thank you for sharing that. I’ll split when I’m ready and I’ll do what I need to do. That’s very well said.

Well, thank you Jim Carey! So, what’s next for you? What do you see in the future?

I am on my way to a book signing in New Jersey which is right across the street from a terrible go-go place I used to go-go in when I was younger.

Wow.

I know, it’s really interesting, Cecily. I’m continuing to create, and there’s going to be more music and more shows, and who knows what’s coming, but I feel like it’s going to be really good.

Jacket by The Blonds, Bangles, Cuffs, Earrings and Hat by Glynneth B.

Jumpsuit by Any Old Iron, Shoes by Christian Louboutin

Dress by Gucci

Makeup by Etienne Ortega @ The Only Agency using NARS and KKW Beauty, Hair by Castillo @ Tack Artist Group using Sexy Hair styling products & T3 styling tools, Art Direction Louis Liu, Editor-in-Chief Marc Sifuentes, Photo Assistant Mallory, DP Vanessa Konn, Gaffer Zachary Burnett, Production Assistant Benjamin Price, Produced by XTheStudio.com, Special Thanks to Jack Ketsoyan, Laia and Mikey Minden

Costume Institute Benefit on May 7 with Co-Chairs Amal Clooney, Rihanna, Donatella Versace, and Anna Wintour, and Honorary Chairs Christine and Stephen A. Schwarzman

Costume Institute Benefit on May 7 with Co-Chairs Amal Clooney, Rihanna, Donatella Versace, and Anna Wintour, and Honorary Chairs Christine and Stephen A. Schwarzman