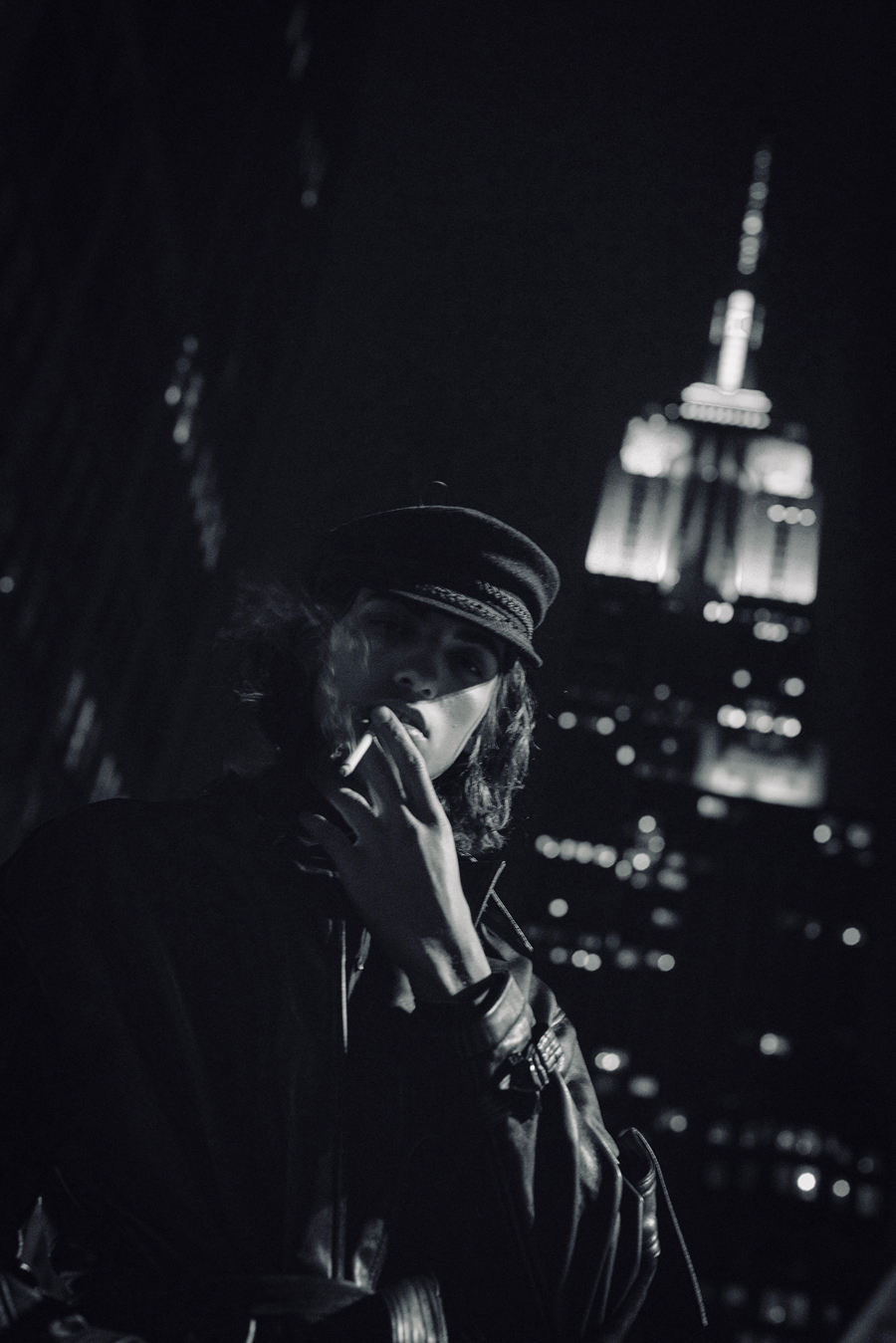

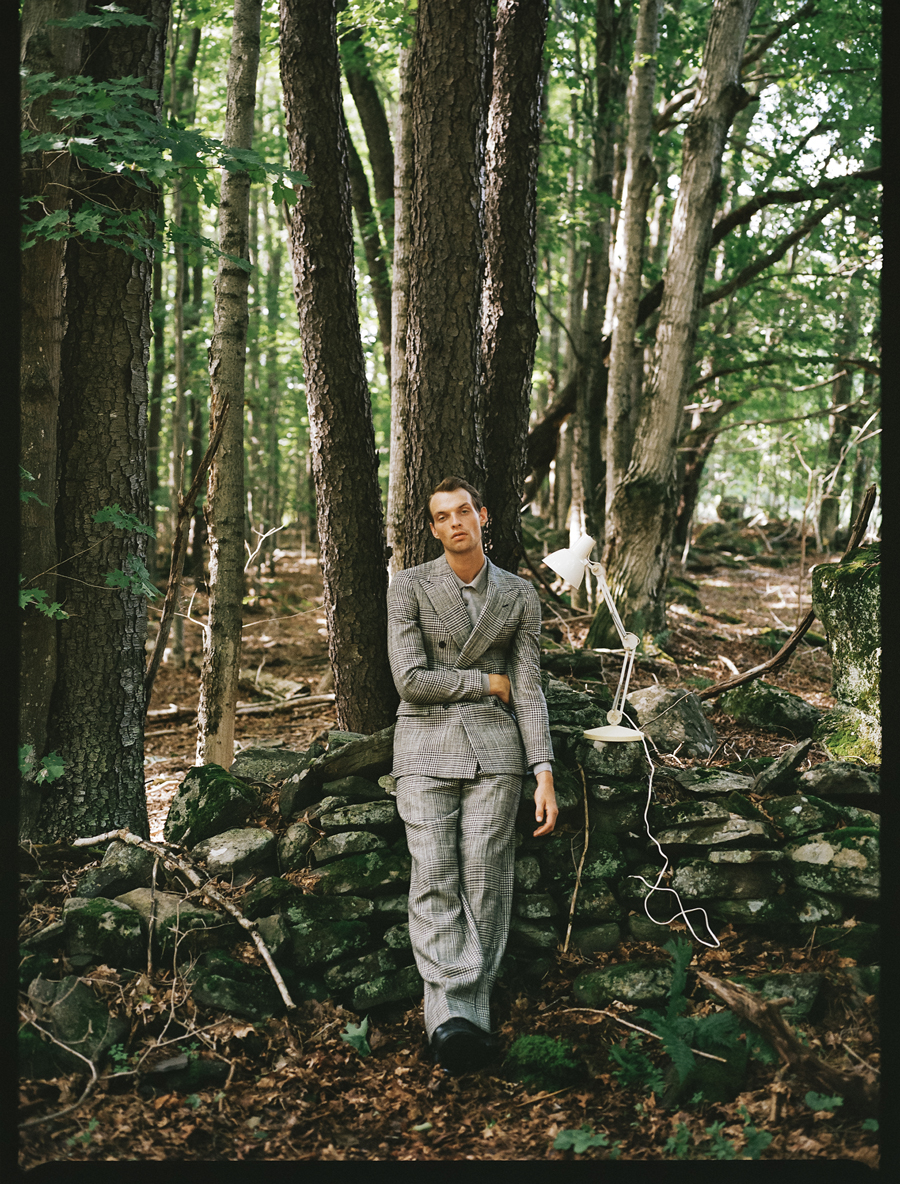

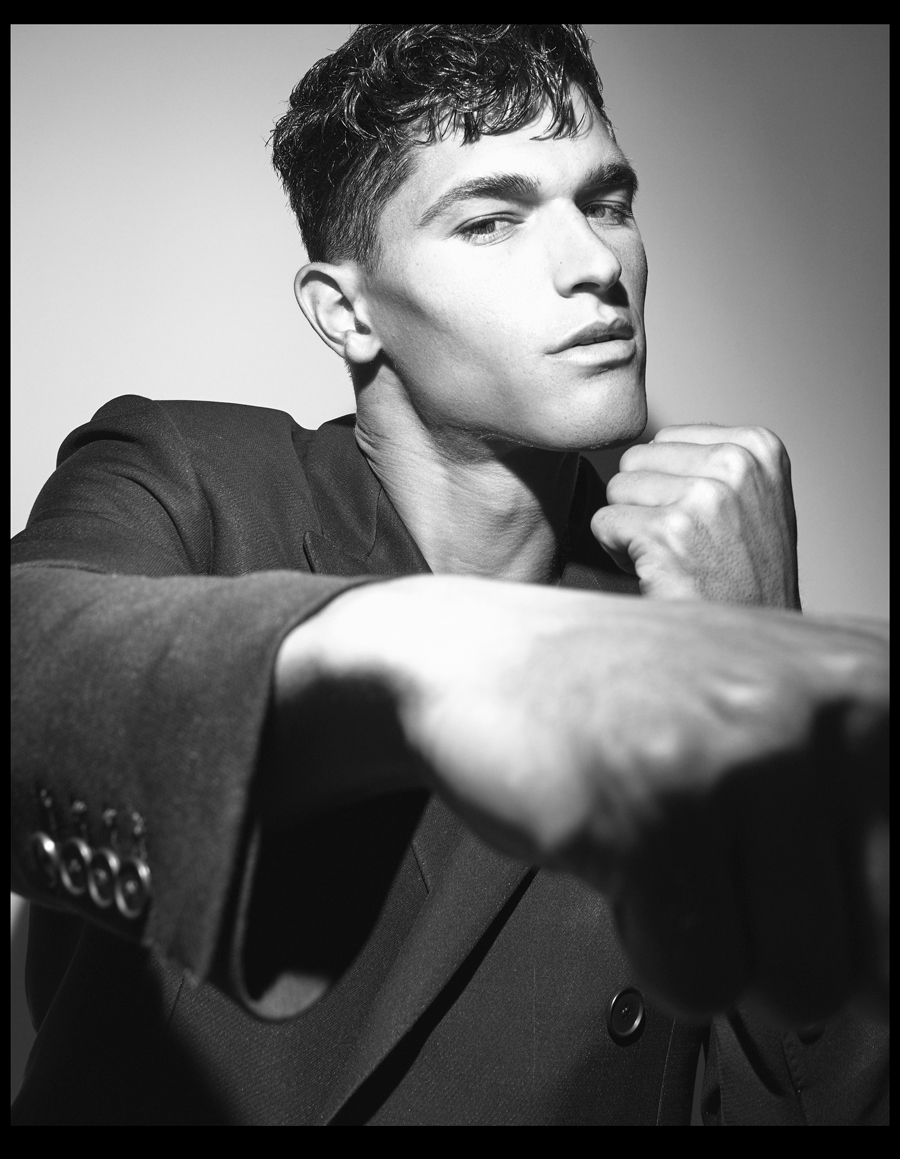

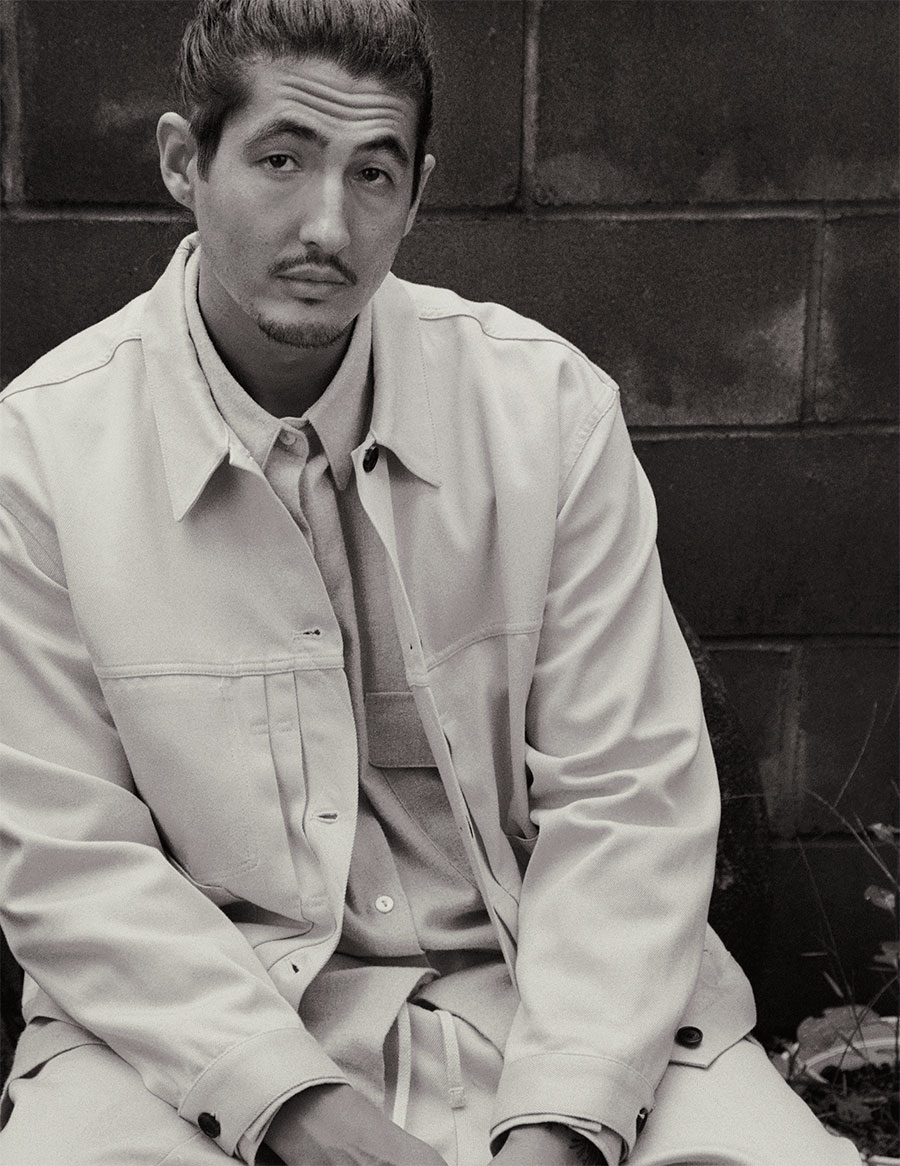

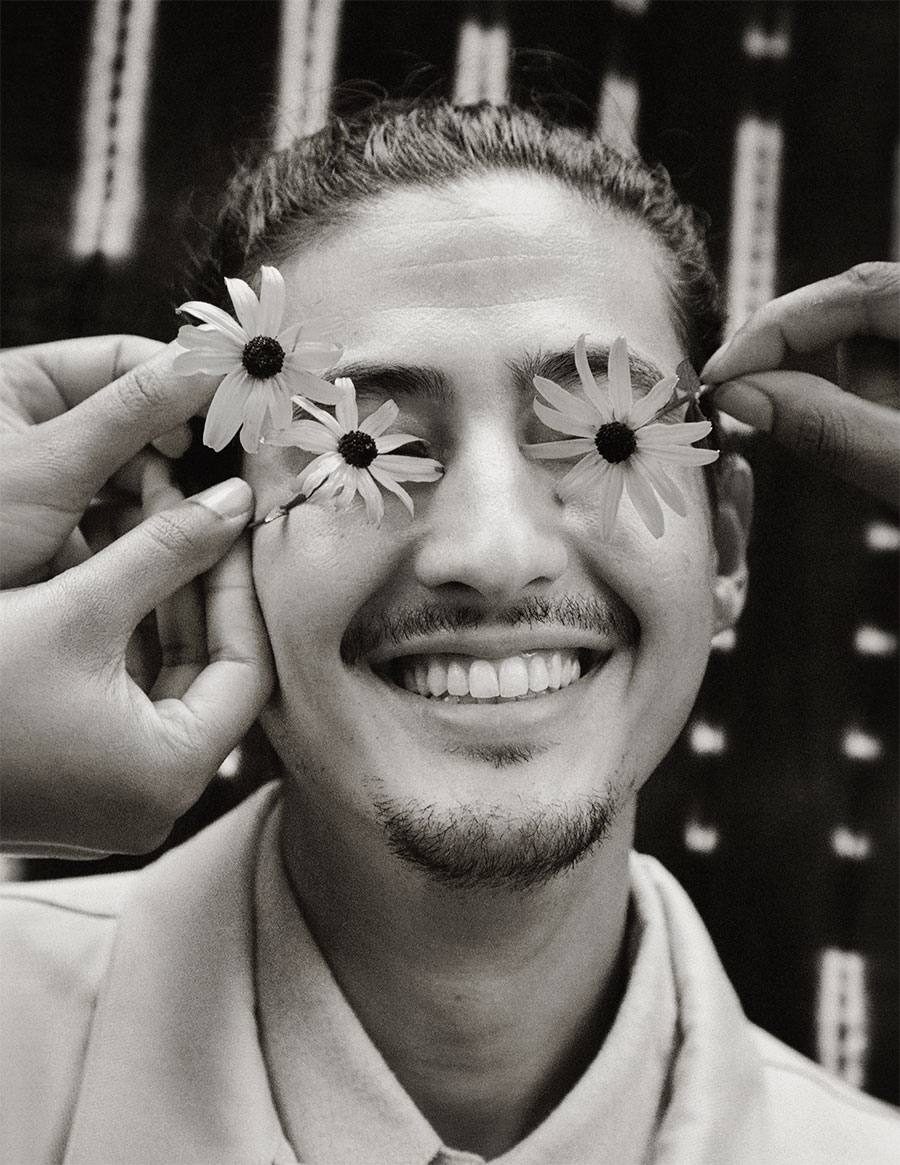

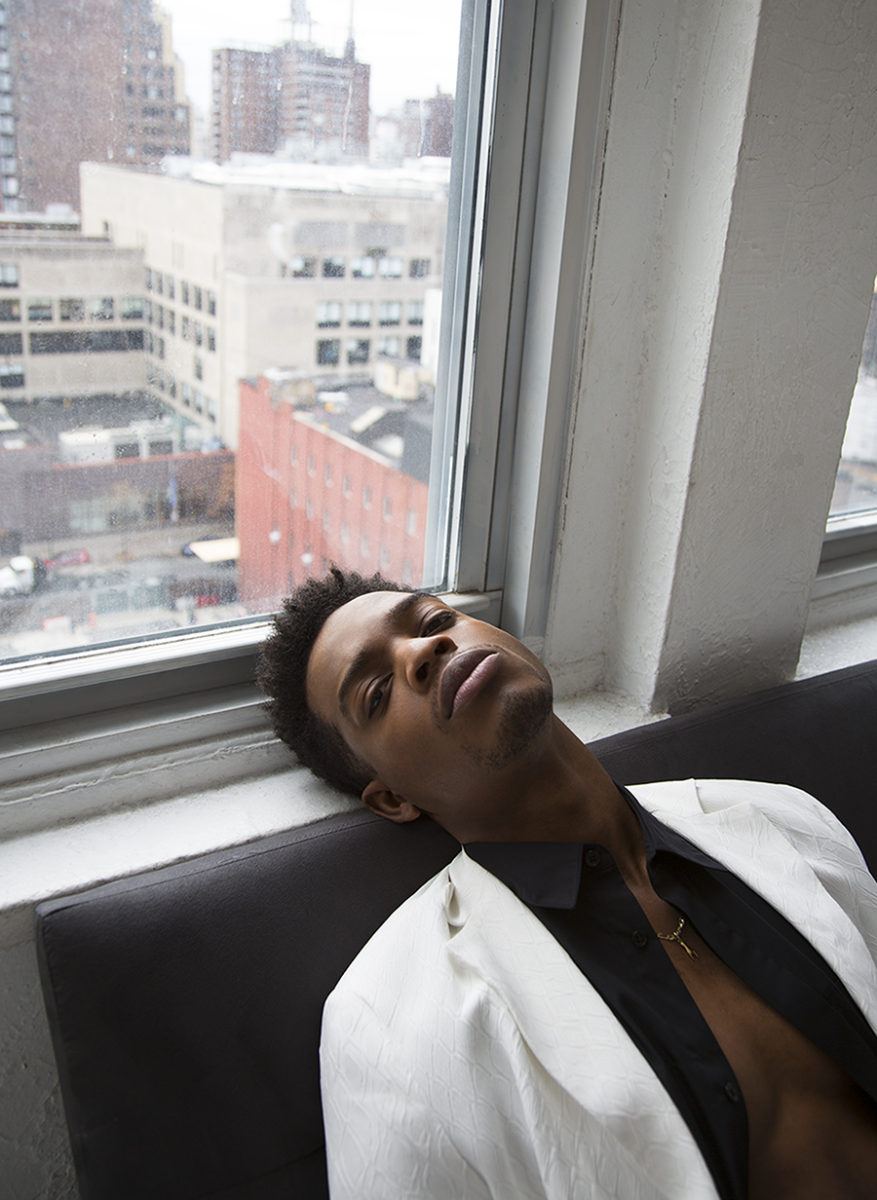

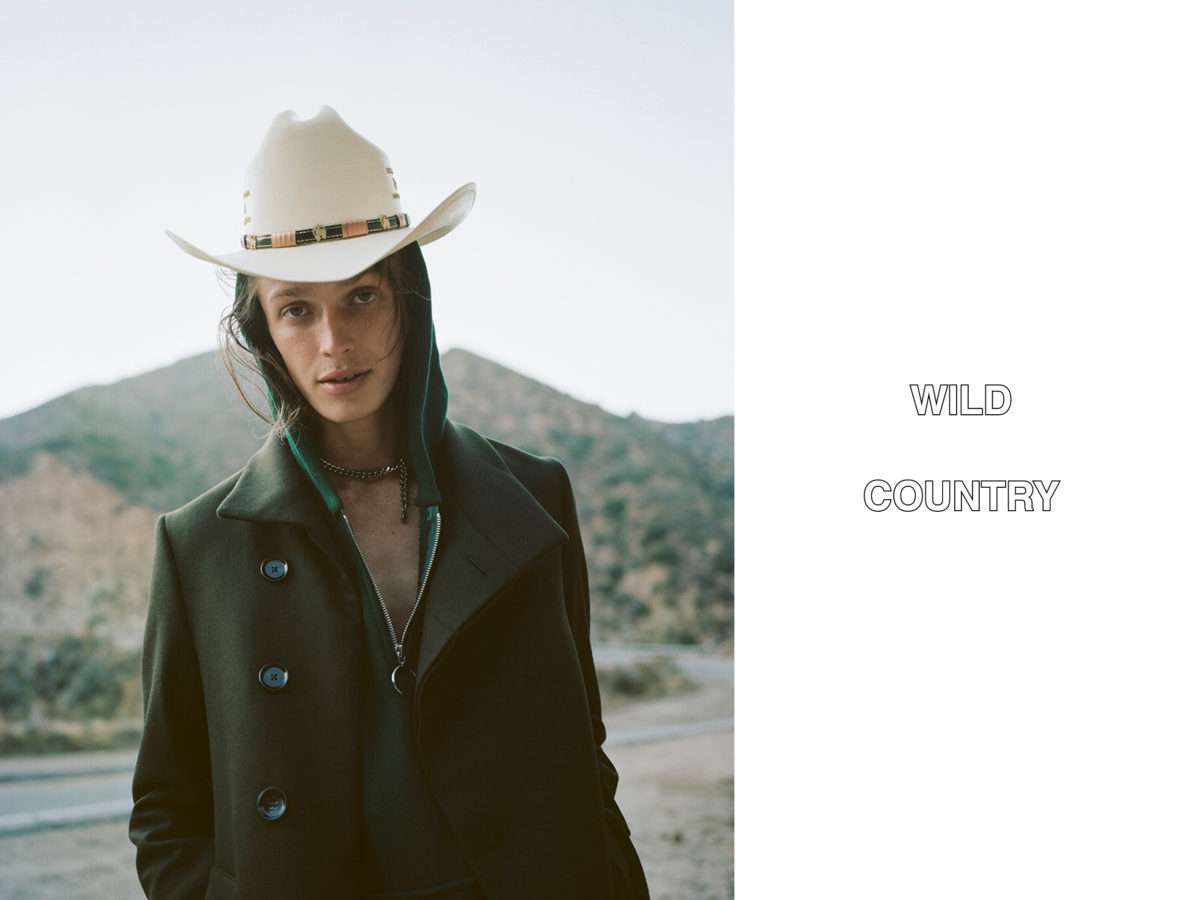

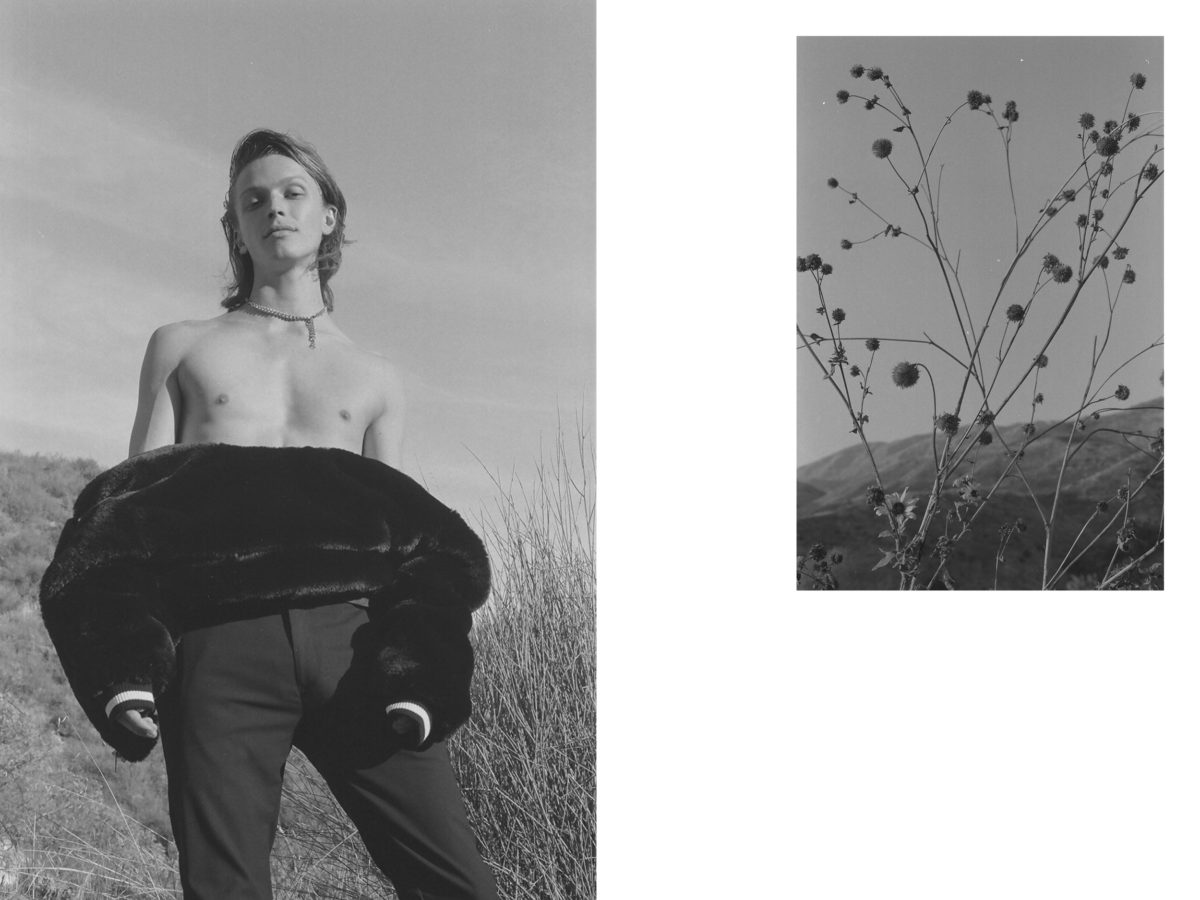

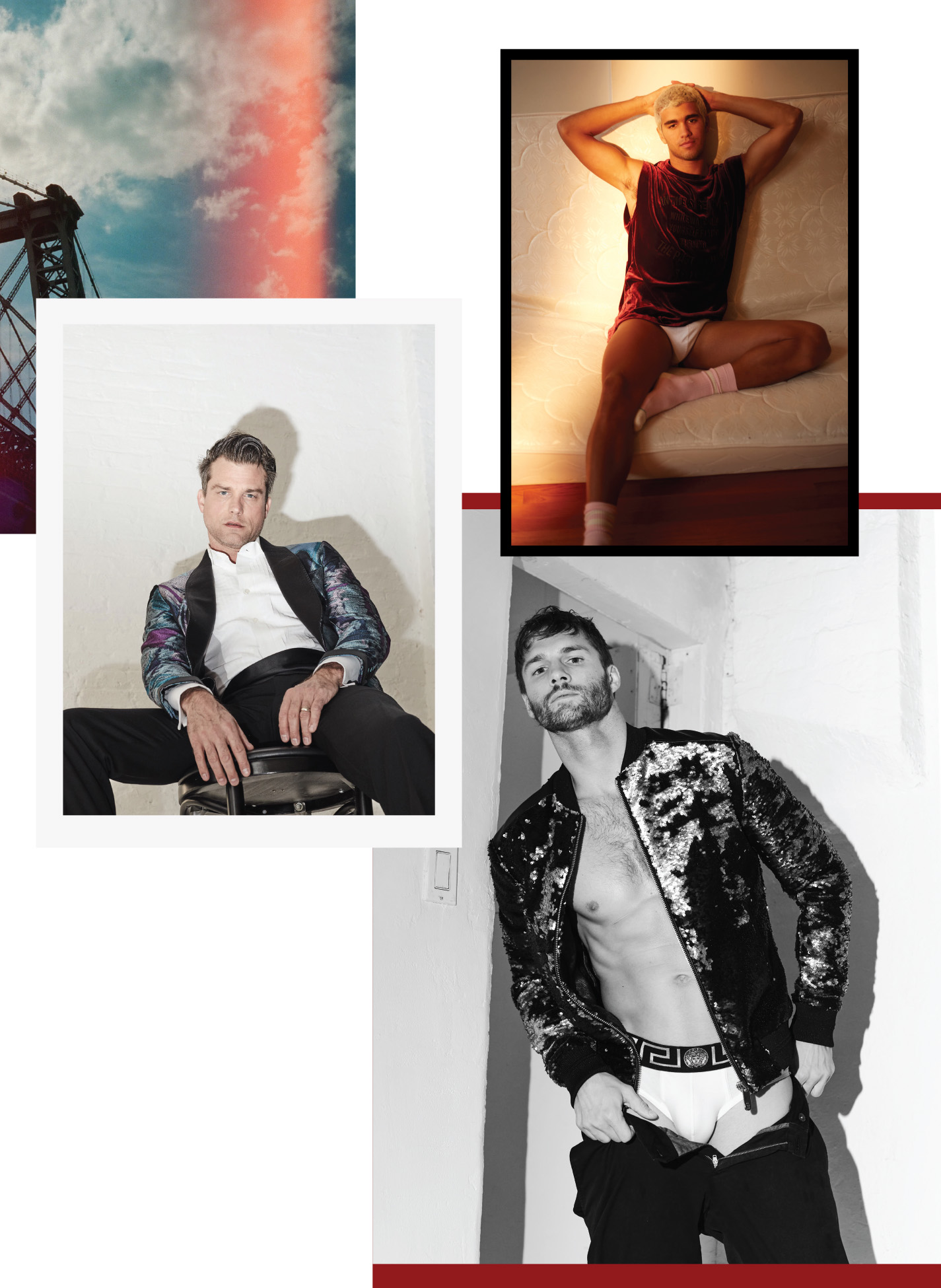

COVER STORY: ORVILLE PECK

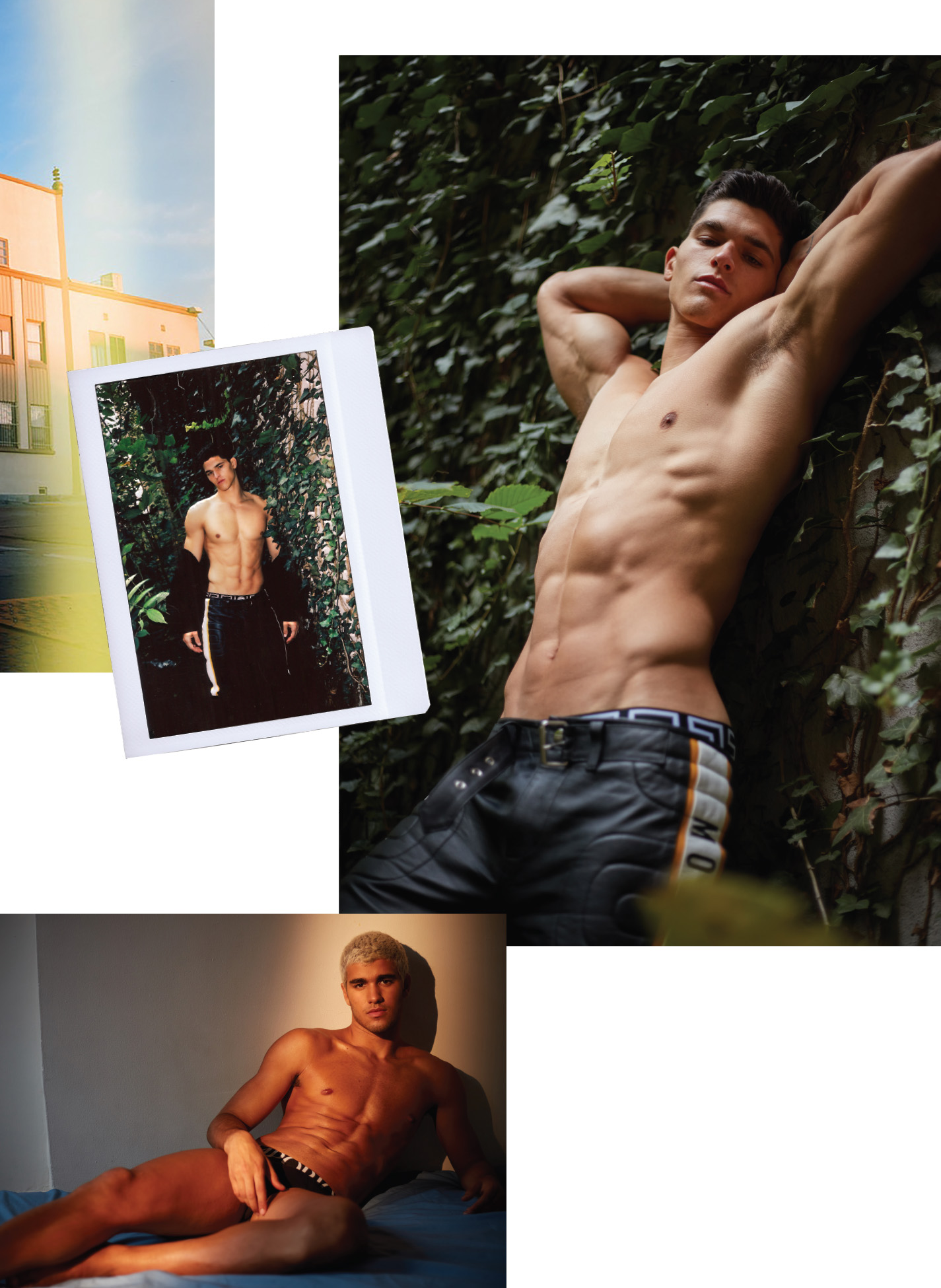

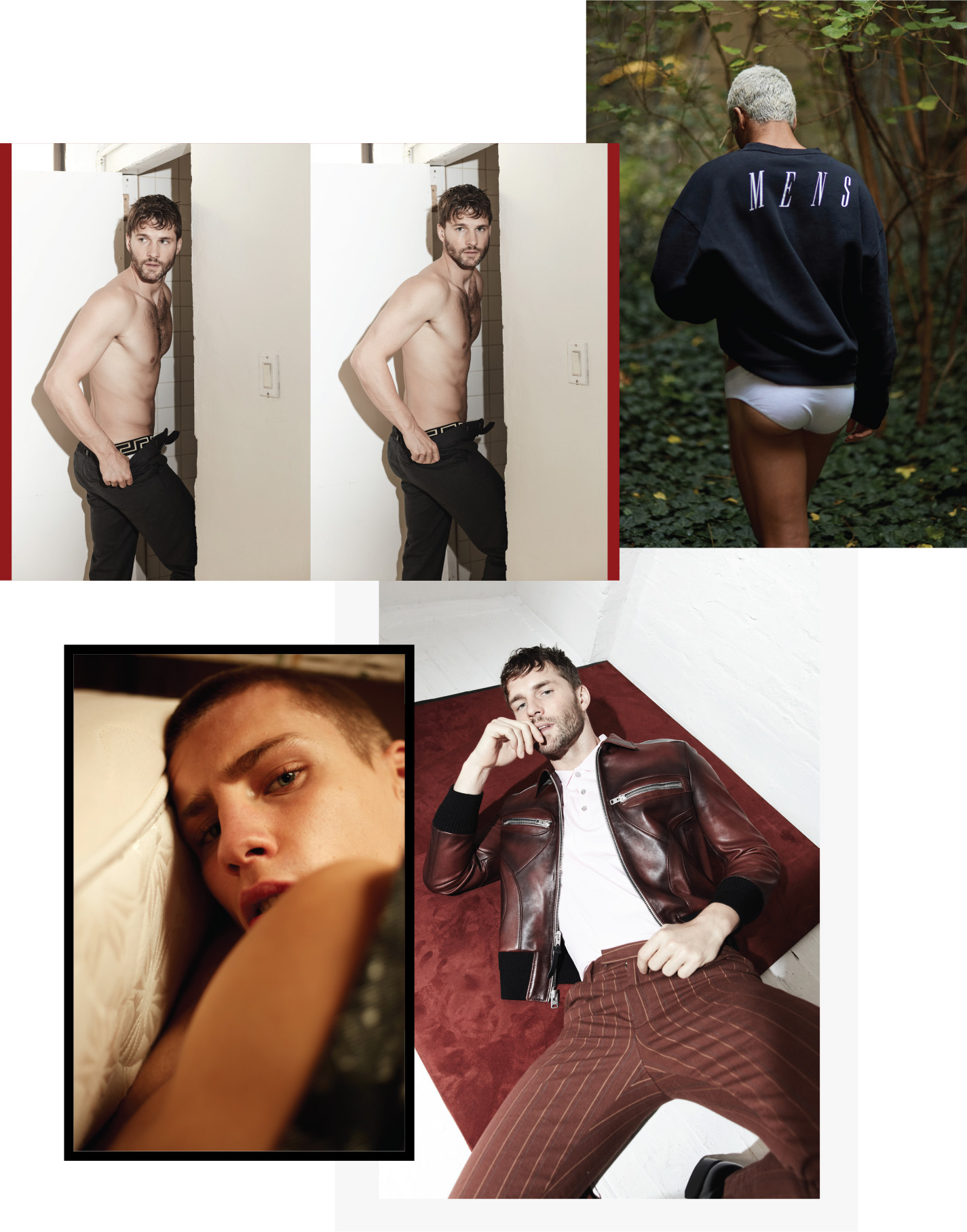

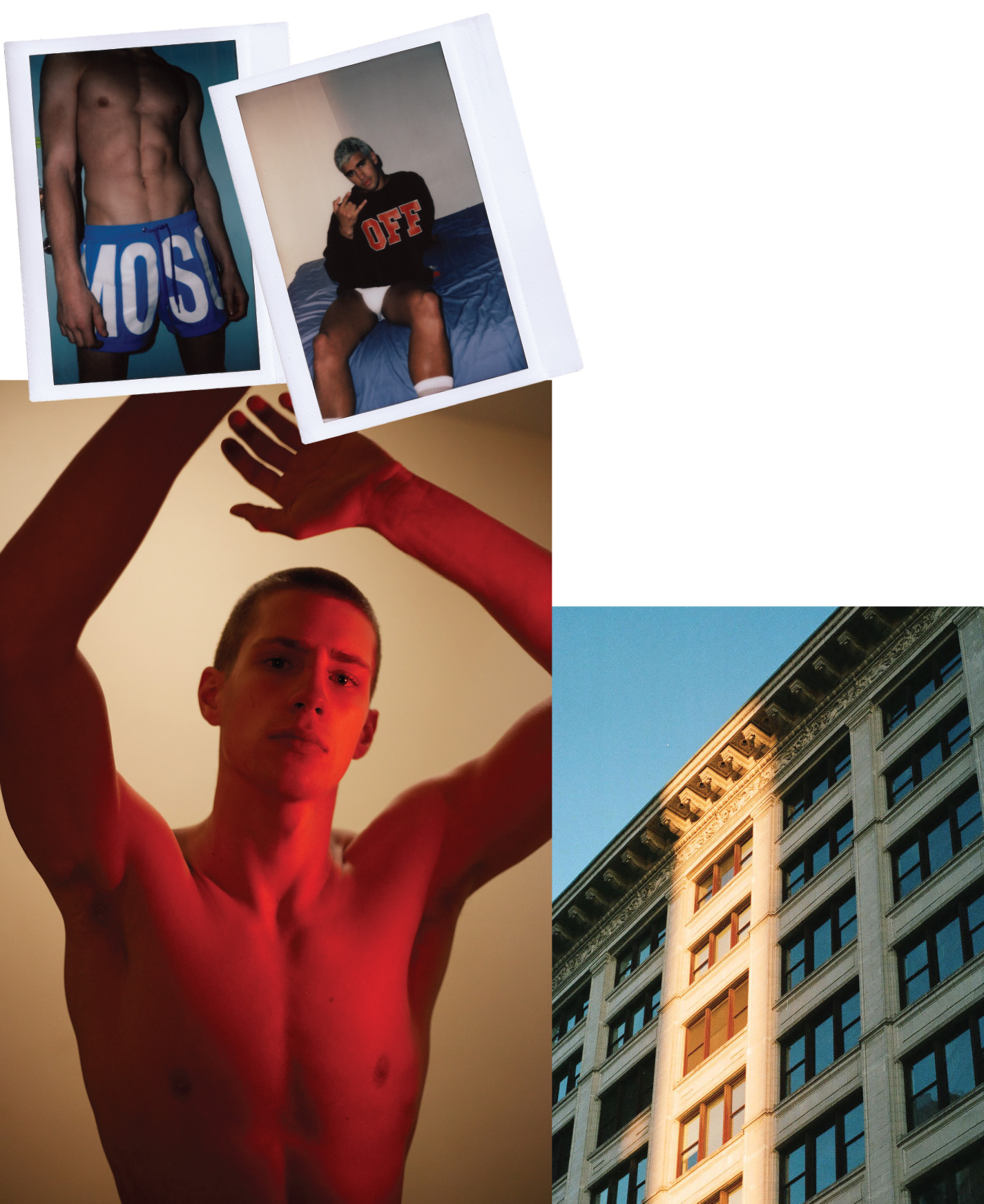

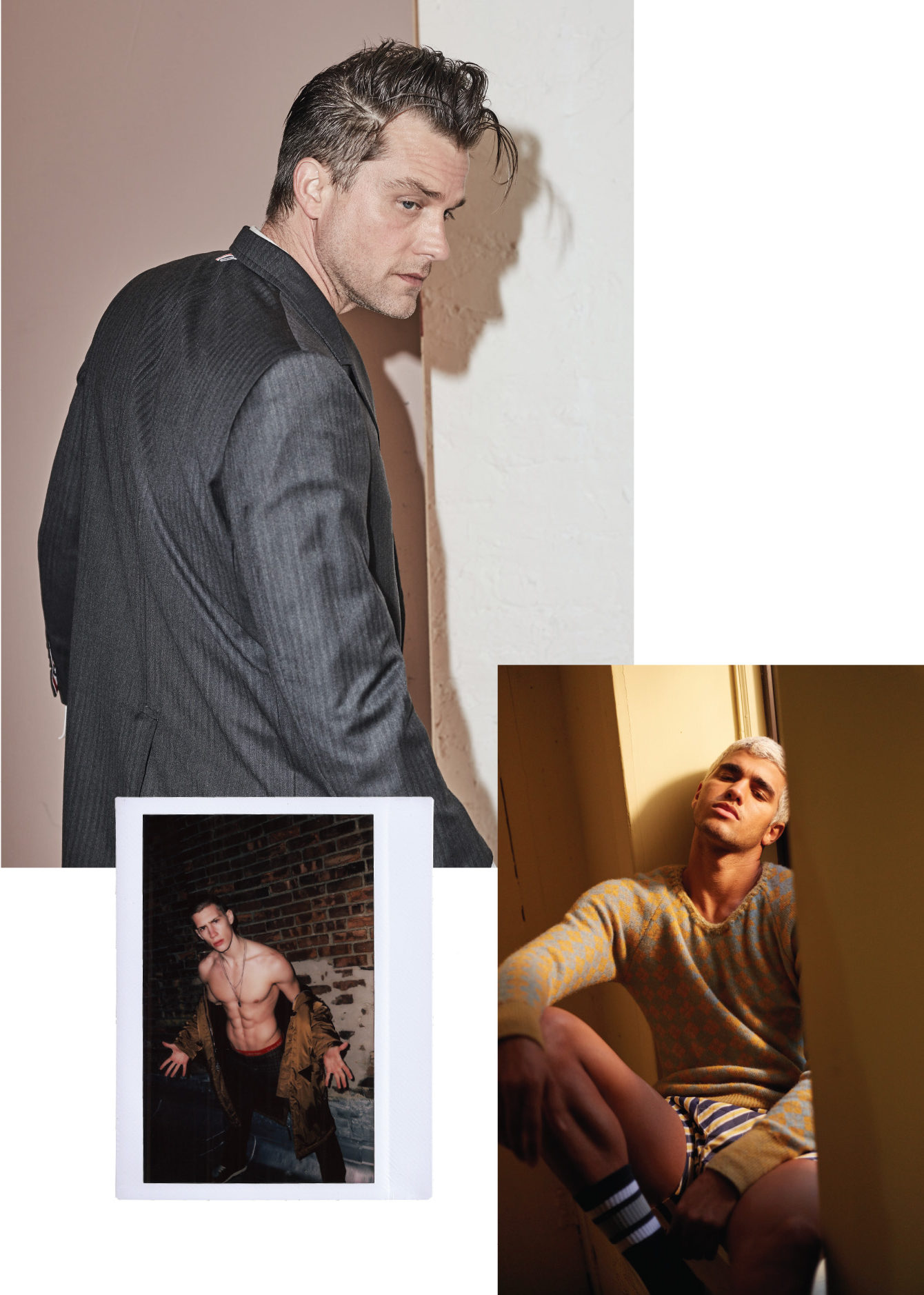

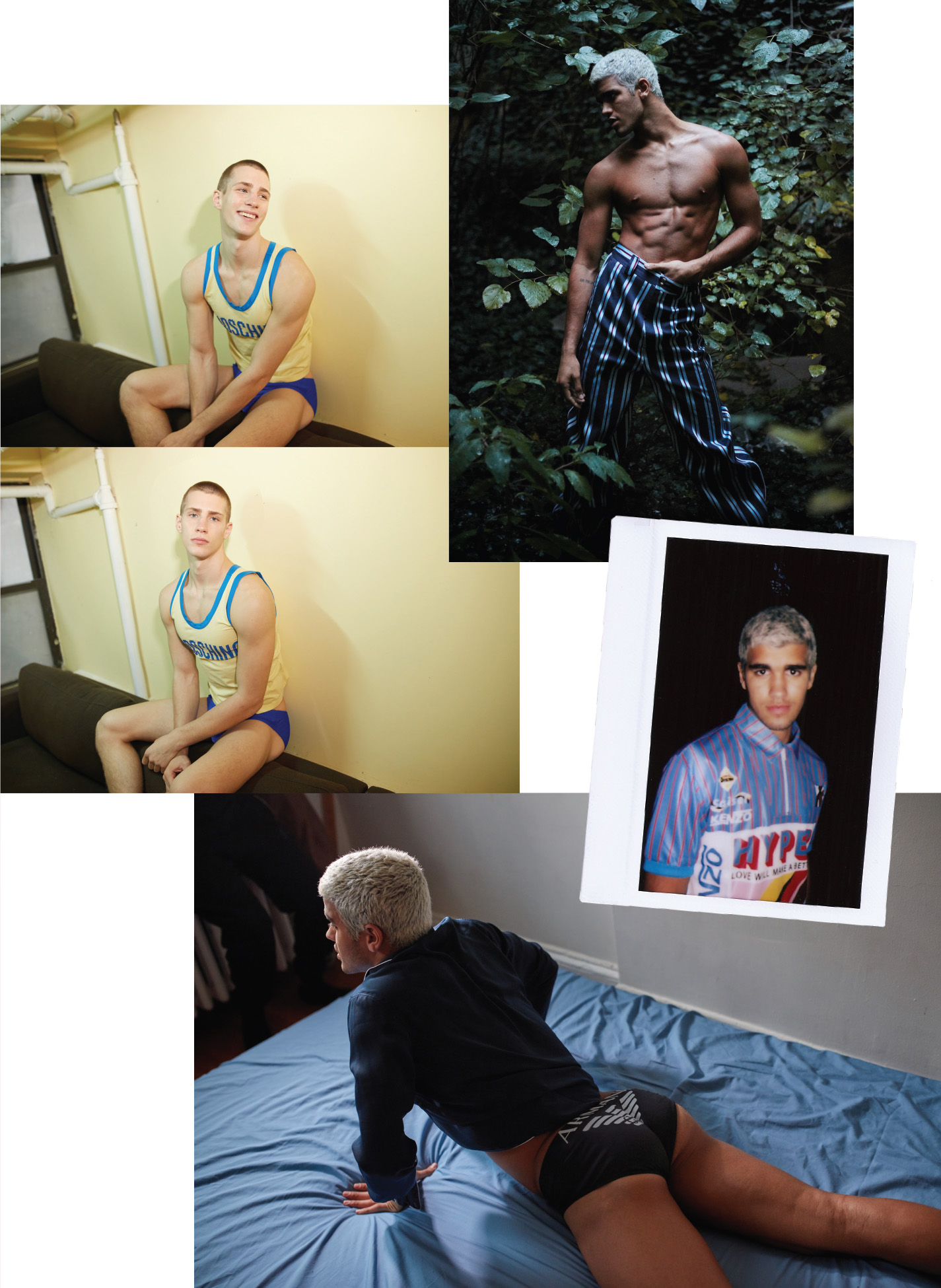

Photographer: Emma Craft @emmacraft

Stylist: Angel Emmanuel @angelemmanuel

Photo Assistant: Michael Decristofaro @m.decristo

Editor in Chief: Marc Sifuentes @marc.sifuentes

Creative Director: Louis Liu @herecomeslouis

Interview by: Dustin Mansyur @dmansyur

With his fringed masks, rhinestone suits, and shoegazing lyricism, Orville Peck is every bit the part of “lonesome outlaw”. Reimagining tropes of tradition, Peck’s take on country music reinvents the genre as a decorated landscape ready for queer expression.

Orville Peck is a nomad. Like a cowboy on a cattle drive, home is an elusive feeling; the masked musician who’s been described as every imaginable synonym for “enigma” feels happiest hanging his hat just off the highway in a roadside motel. The open road is a part of his DNA, having traversed and inhabited several continents, countries, and cities as a boy. His incessancy for wanderlust belies a romantic narrative spun in the stories of his songs, lulling his listeners on a quixotic journey through a memoryscape evocative of another time and place.

Releasing Pony in March earlier this year, Peck’s sincere approach to his storytelling and lyricism is reminiscent of Lucinda Williams or Patsy Cline, intimate and unadulterated. His vocals are as hypnotic and coaxing as a desert oasis on Route 190 through Death Valley. Somewhere between the inexplicable pain of loss resides the unparalleled elation of love and lust. It is the proverbial longhorn skull and rose motif. As a queer artist who croons about gay hustlers or doomed love affairs, his sincerity is the foundation for his music’s transcendency, appealing to longtime country music fans while attracting a younger, more diverse audience to the genre. In an era demanding the commodity of content, Peck deciphers himself apart from the formulaic clout of music industry contemporaries through his visceral ability to be truthful. It is this vulnerability that cannot be faked nor bought, and an even rarer quality for a performer as sensitive as Peck, fearlessly weaving the stories of his experiences and muses into the embroidery of his album; Pony is forthcoming and unapologetic. While the illusion of his shrouded pageantry may have him pegged as the “musical outlaw”, coupled with the intimacy of his music, it creates a contrasting dichotomy that is equal parts mystifying and infatuating.

Ready to saddle up and lead a cavalry of change in the country music industry, IRIS Covet Book shares a conversation with the artist just before he embarked on the European leg of his tour.

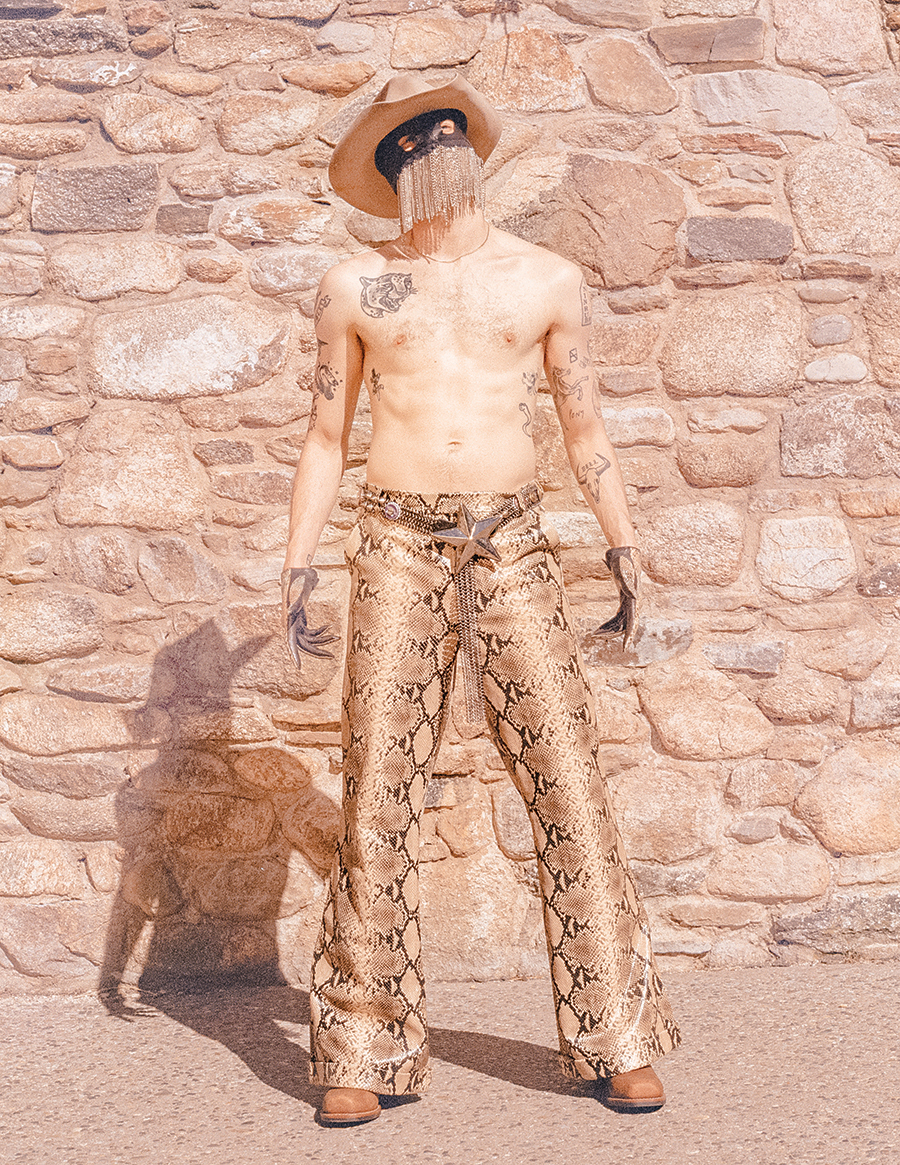

Jacket from Screaming Mimi’s Vintage, Hat: Stetson, Gloves: Maison Fabre, Necklace: His own

Listening to your album, really took me back to my experience as a gay person of color who grew up in the rural Midwest on country music, struggling to find acceptance in the 500-person town I was raised in. Because of your music’s authenticity, one might easily assume you had a similar experience. Where are you from and what was your experience like growing up?

I mean I grew up in a bunch of different places, by the time I was in my early twenties I reckon 5 different countries and many many cities. I’ve lived in Africa, in Canada, in the States, and in Europe—so I moved around a lot. My parents were both from kind of humble beginnings and whenever they did kind of have any money they would put the emphasis on traveling and getting to go and experience new places and cultures. So I think I grew up with a pretty diverse view of the world, in general, but especially in music and art. And I think country music always connected with me because, not only did I love the instrumentation and the themes, but I also related to the environment that it’s set in. I was born and grew up in a desert area, so there were obvious connections to it. As a young gay weirdo, I was really drawn towards the campness of it, the bold storytelling, the theatrical nature of it, which also ran kind of congruent with a lot of sincerity, heartbreak and loneliness which are all kinds of things that I felt and I still carry around with me now.

It’s funny because country music has this stigma surrounding it that it’s supposed to be for well-adjusted conservative, aggressive, white men. It’s sad because like you said yourself, a lot of queer people of color or marginalized people that grow up in small towns feel outside of country music. But the stories within country music—even going back to artists like Patsy Cline—I think those stories speak clearly to people like us. I think also that’s why it’s so obvious that someone like Dolly Parton is such an icon for gay people because she’s someone that had to blaze her own trail and really really convince people to listen to her by dressing provocatively and wearing crazy wigs and essentially being, you know, like a drag queen. But, she could also write some of the most heartbreaking gut wrenching songs of our whole civilization. I think country music has always been written by outsiders and it’s always been for outsiders. I hope to help to break that stigma down because it’s not supposed to be only for white men in trucks or whatever.

How did you break into the music industry; was it something you always imagined you’d be doing?

I was a performer since I was about 10 years old. I started with acting and I was a dancer for a long time and I’ve always been a singer. There were always instruments around my house, I never had formal lessons but I taught myself how to play guitar and piano. I think I just always knew that I was going to be a performer in some way. I’ve been in a bunch of different types of bands all through my twenties, but I knew that I always wanted to make country music and I always wanted to really sing and I never had the confidence to do it for a long time. Then I took a break from music for about 6 years at one point and then when I came back to it I knew I wanted to do country music because it had always been in the back of my mind.

You’ve toured extensively with punk rock bands. Do you find a correlation between the genres and your approach?

Definitely, there’s a similar rebellion, of course. I think there’s a similar aesthetic in some ways. The punk that I grew up loving was early seventies kind of punk. Those people all had pseudonyms; they all had costumes that they wore. You know they spent more time on hair and makeup than most musicians probably do now. So I think that there’s a lot of correlations between country music which is essentially pageantry and drama mixed with vulturous sincerity and heartbreak and I think that that’s kind of what punk is too.

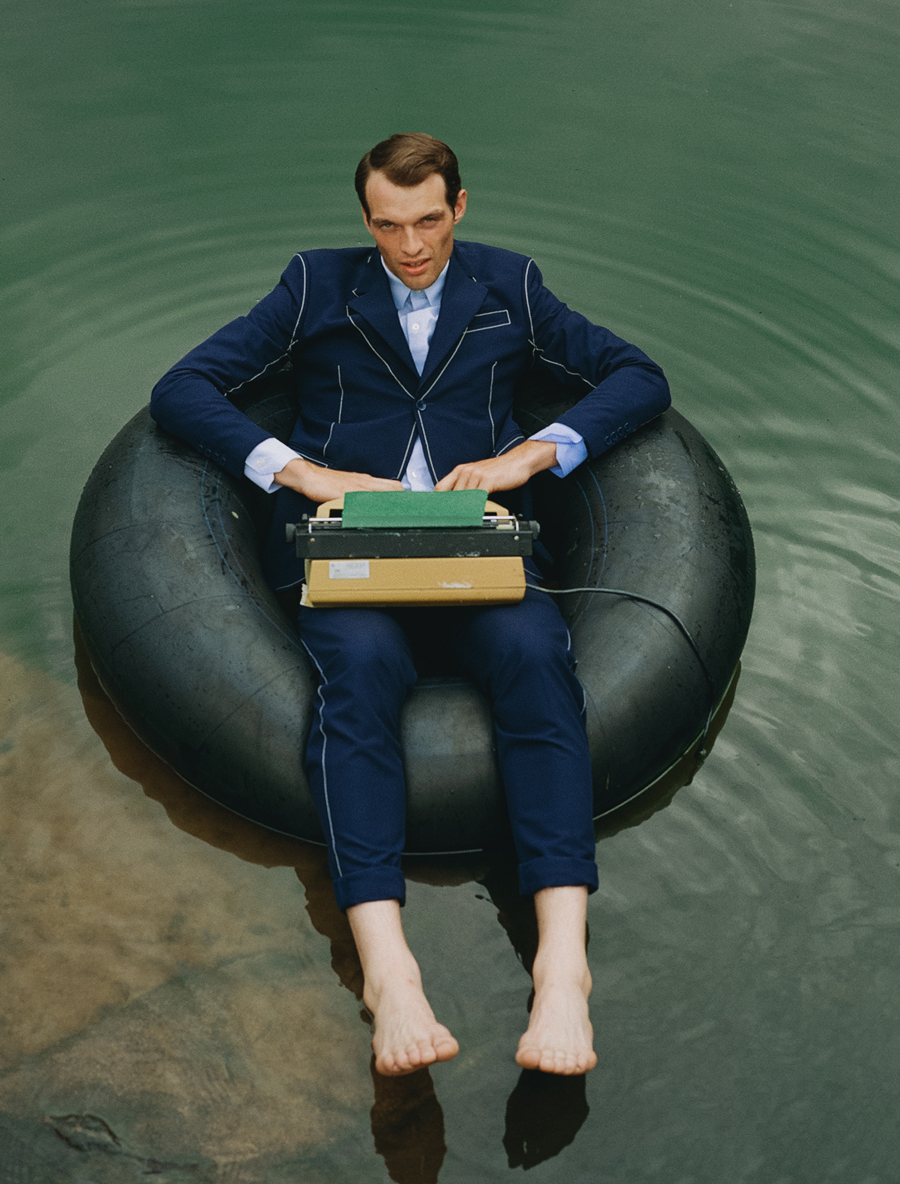

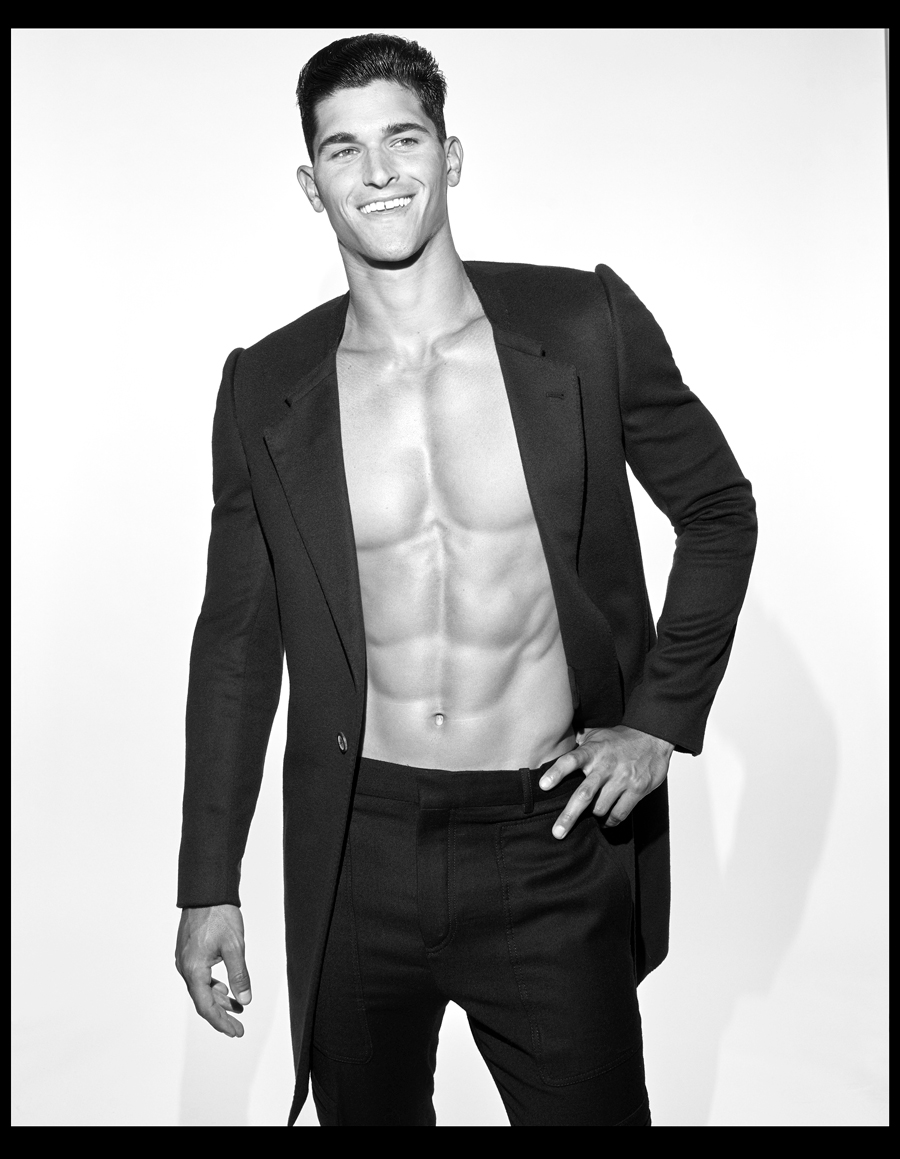

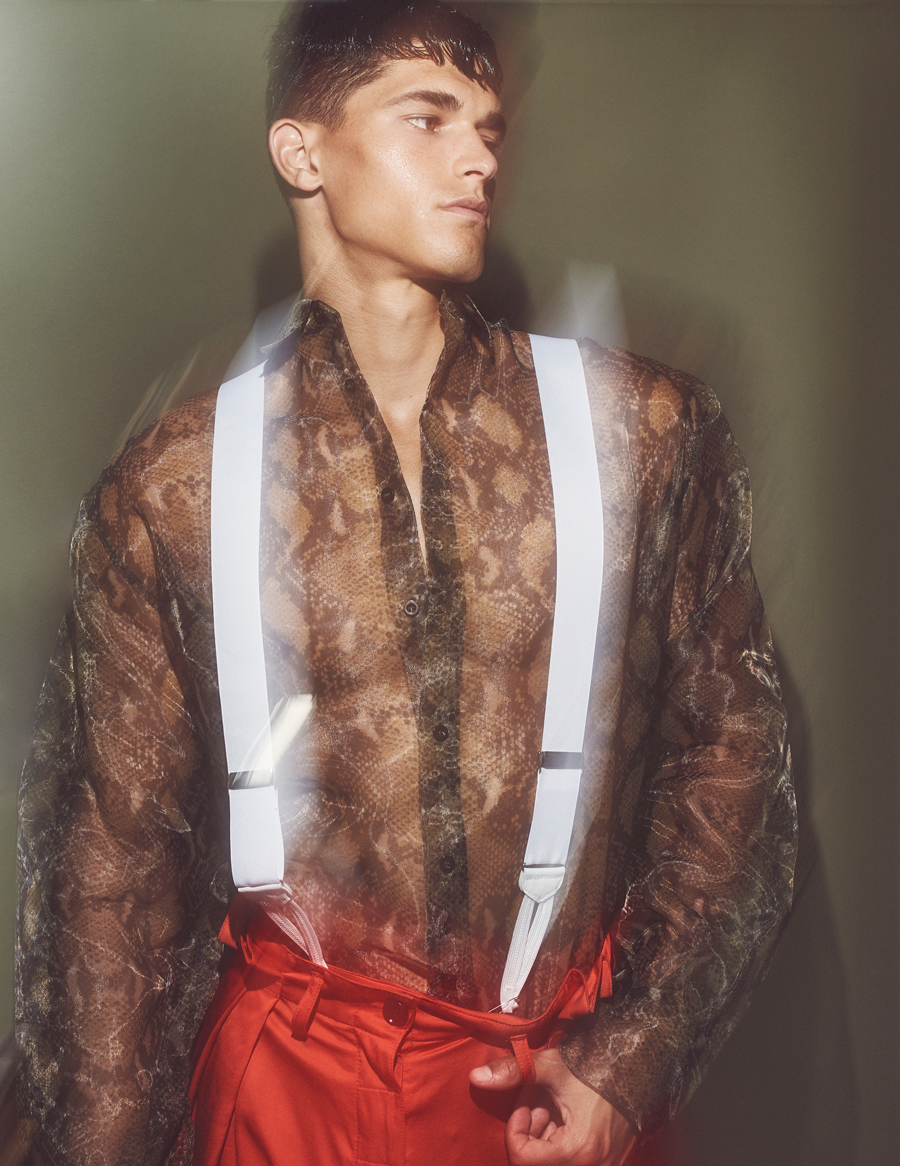

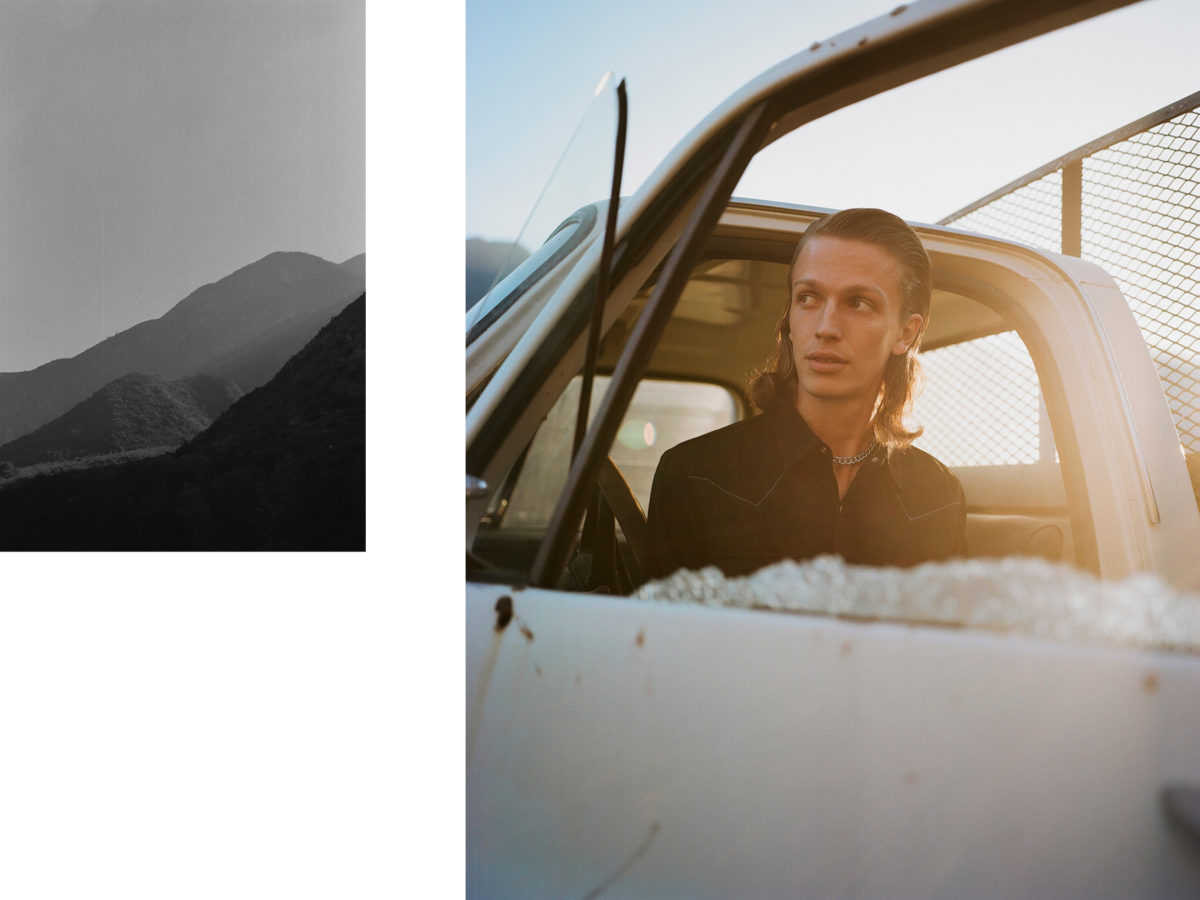

Shirt and Jeans: R13, Vest and Chaps from Screaming Mimi’s Vintage, Hat: Stetson, Boots: Star Boots

Returning to country music, did it feel like you were returning to your roots in a way?

What I do now feels so easy in a way because as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that it’s the easiest thing to just be yourself. The best qualities about you are the most sincere ones. Of course, I still struggle with insecurities about it and I have self-doubts, but the older I’ve gotten, it’s become easier for me. Even though I’ve been a performer for so long and been doing it as a job for a long time, I think this time I can really sit back and enjoy it for the first time because it’s become fun and easy to be myself.

You’re about to embark on your European Tour for “Pony”. You’ve described yourself as a “born drifter”, which kind of furthers the romanticism of your musical canon and persona. What is it about the open road or a nomadic lifestyle that calls you?

I’ve just always felt anxious. As I’ve said, I moved around a lot when I was younger, so I think the idea of moving to new places and kind of making your home wherever you are—that’s always just been part of me I suppose. I find it very hard to put roots down. Oftentimes I’ve tried to stay in cities for long periods of time and I’ve always kind of gotten anxious and not really known where my place is. Part of what appeals to me now is that I’ve learned to really find the adventure in it and not look at it as a downside. When people ask me where I’m from and I say lots of places, it’s not to be obtuse or enigmatic, it’s just because I genuinely feel like I have left little pieces of myself in all these different places that I’ve lived. That to me is so special because I can go back to those cities and feel like I’m right back at home in a way that I’ve gotten to meet incredible friends and family all over the world. So I think those are things that appeal to me about it. I’m just someone that’s never been able to sit still.

Do you feel most at home when you’re on tour?

Yes, I do. I definitely feel most comfortable. When I’m stuck in one city and I have a lot to do like I am right now— I’m about to leave in two days again for tour—but I tend to have the most anxiety and stress when I’m stuck in one place. I do feel at home on tour; I just feel at home when I’m traveling.

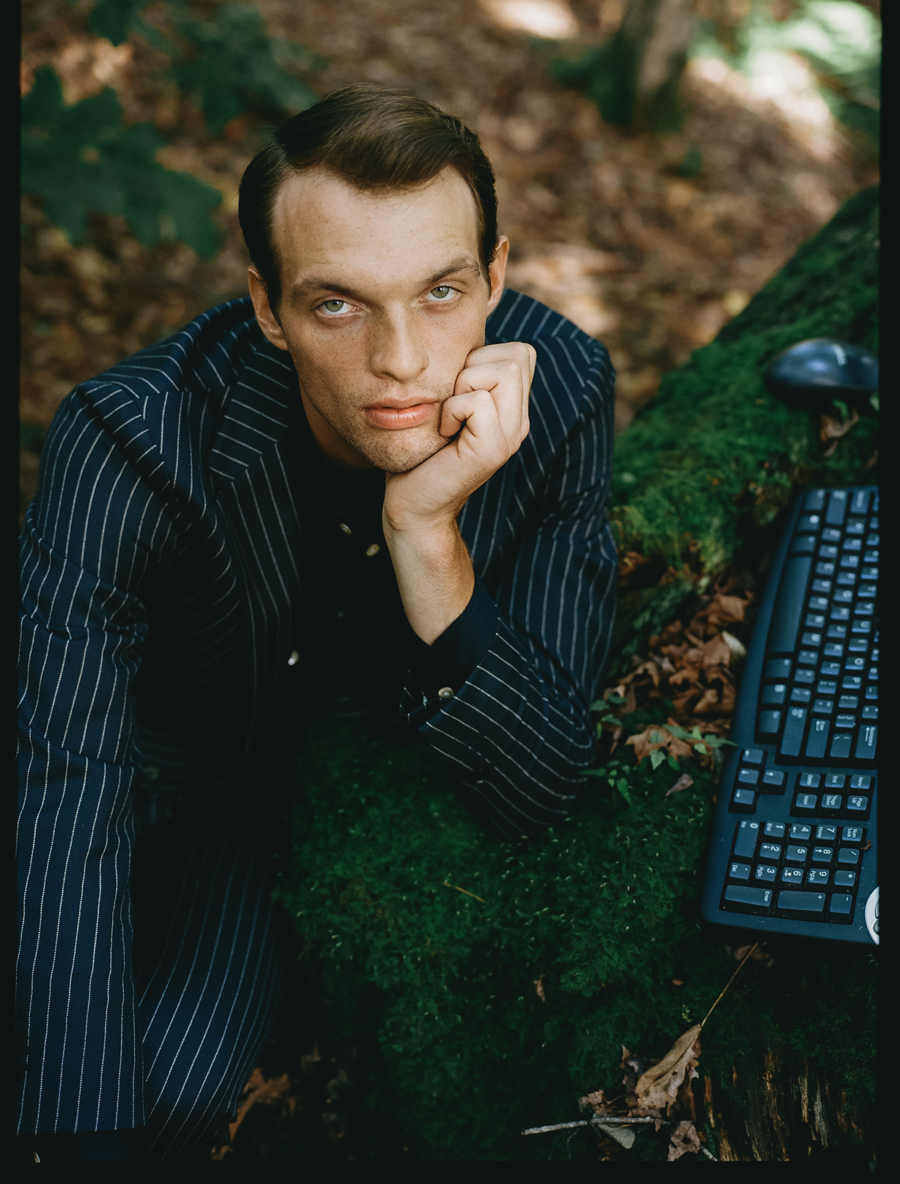

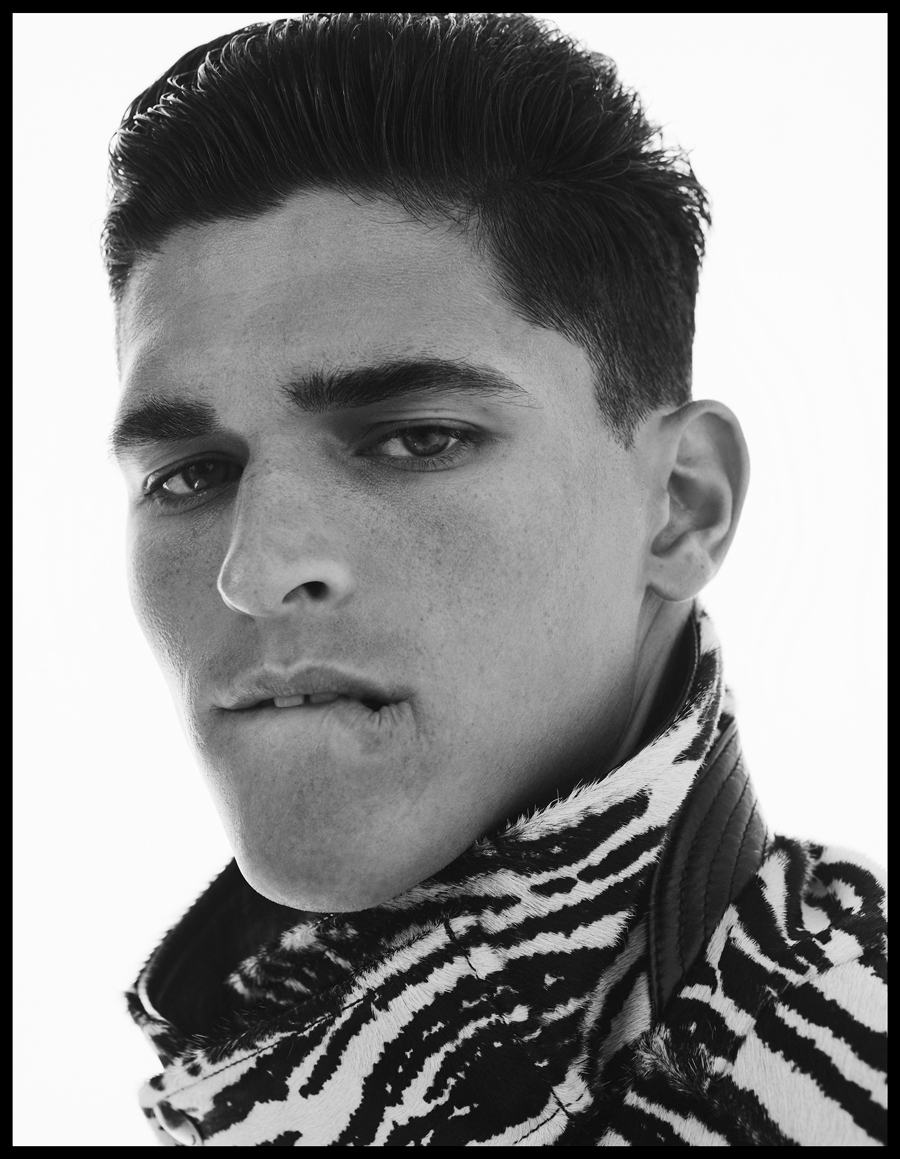

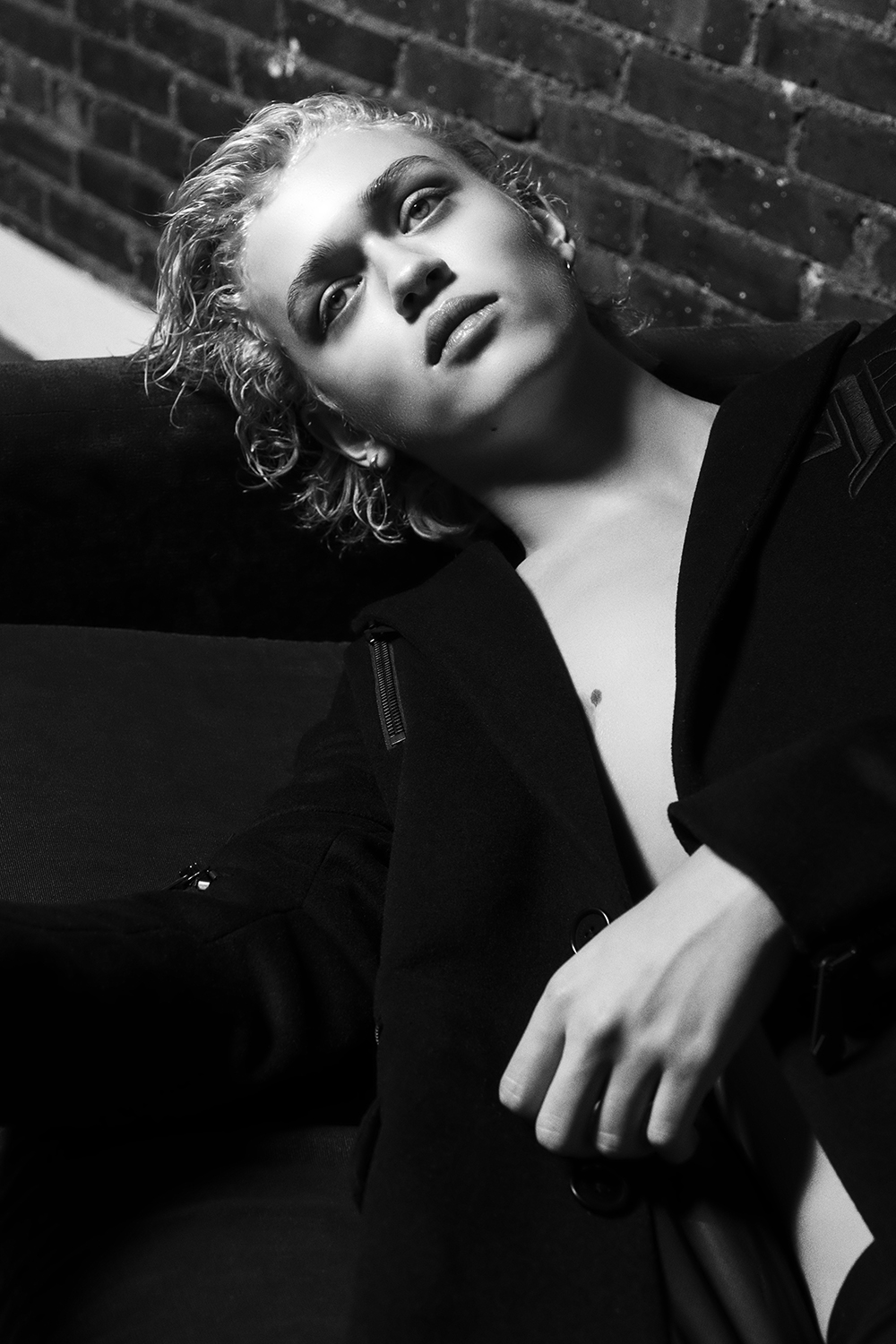

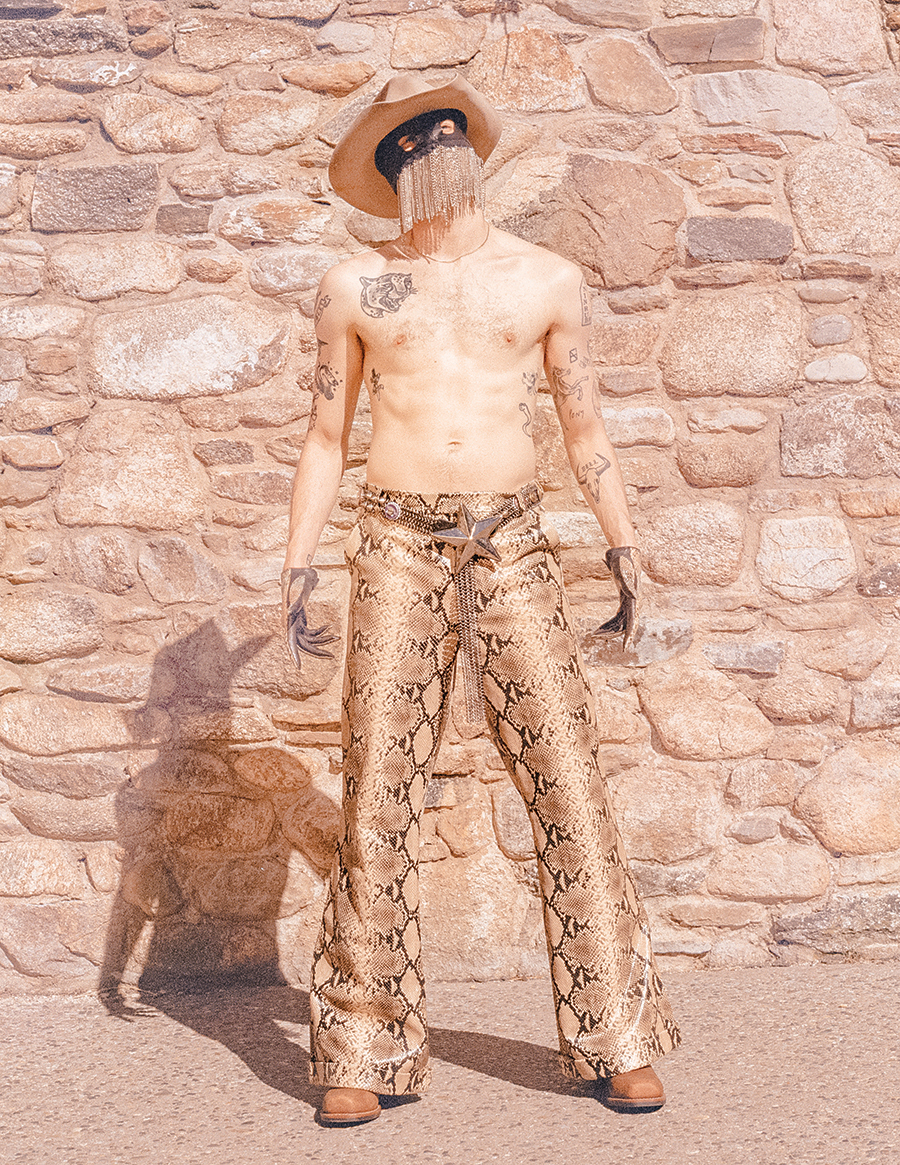

Pants: Gucci, Hat: Stetson, Gloves: Wing + Weft Gloves, Belt: Diesel, Belt Buckle: Stylists Own, Boots: Frye, Necklace: His own

What is your song-writing process? How often do you write? Is it an ongoing discipline or something you do only when you apportion studio time for it?

I’m kind of writing all the time. It’s all different. Sometimes it’s an idea just based around a concept for a song. Sometimes it’s based around a melody that I have in my head. Other times it’s based around one lyric or a line that I want to try to incorporate. Oftentimes I start from more of a visual or kind of an emotive place where I know what kind of vibe I want the song to be or what emotion I want to evoke for the person listening to it. Then I go from there by making it personal to me and hopefully telling a good story at the same time.

Pony was released in March earlier this year and received with splashy critical praise as well as excitement from your fans who’ve been waiting for it since your single release of “Dead of Night” in 2017. What are you most proud of about the album, and can you share any personal anecdotes from the recording process?

What I’m most proud about and just generally about the past year is that I’ve been able to express myself as an artist. That includes collaborating with people, which is something I never used to be very good at doing. I’ve learned in the past year to really embrace that. And I find it really fun and exciting now being able to work with people on videos, visuals, aesthetics, stylists… as an artist I think it’s really important. Then in addition to that, getting to do what I’ve wanted to do since I was little, which is to be a singer and really sing, and sing about heartache and things that are important to me and things that are sometimes difficult for me to sing about. I think the bonus of that is everyone enjoying it; it’s more than you could ask for and I find it very fulfilling.

I’m curious if you ever struggled with proclaiming yourself as a gay artist right from the start or did you ever feel that you would embark on your career and let it come out naturally? How important is it to your brand?

I’ve never struggled with it. I think it’s important to me and it’s also not important at all in a way. As an artist, if I’m going to write songs with any kind of authenticity they’re going to have to be from my perspective and my experiences. And my perspective and my experiences happen to be of someone who has been with men. To me it’s kind of a non topic in a sense, but not because I’m dismissive of it, but because to me I’m just following in the footsteps of every other singer and songwriter who sang about the people they were with and sang about their problems. I just feel like I’m being genuine to myself so of course it’s going to be about men if that’s who I’ve been with. So I think on one hand it’s a huge part of who I am, what I do, and what I sing about. I’m completely proud and open about being gay and being part of that community, but I also think it could hold just as much weight if it wasn’t my background either.

What has been your greatest internal or professional challenge that you’ve had to overcome as an artist thus far?

My biggest challenge I guess has been trusting and really believing in myself I guess, which is something I learned through the help of other people a lot more in the past couple of years. I always was a creative child. I knew what I always wanted to do; I knew that I could write songs and I knew I could perform and make people smile and clap. But I think I still had a lot of barriers and defenses up,and in some ways I still do. I just never had much opportunity to really collaborate with people growing up, so that’s been a big learning curve for me. It’s interesting because I used to think that opening myself up to working with other people or even really opening myself up to sharing personal things about myself through my art would in some weird way dilute me as an artist. But it’s only just really enriched me as an artist and made it far more exciting. That’s been a struggle for me but it’s been a nice struggle in a way — It’s important to be far more open than I used to be.

Vintage Jean Paul Gaultier top from Screaming Mimi’s Vintage, Hat: Silverado Hats, Gloves: Perrin Paris

Was there a defining moment in your career that proved to be a turning point or breakout moment that propelled you to the next level?

I think a lot of artists and creative people struggle with the fact of embracing that they’re going to do this for real or whatever. Like of course you have to supplement art with an income and usually that means working some job you’re not really interested in and that’s kind of soul sucking. But it’s also about a state of mind, just fully deciding one day that you know you are going to do it for real and you are going to own it. Even though I was a performer since I was very young, I still had those fears. It wasn’t until maybe my mid-twenties that I decided that I’m only going to be an artist and everything else is purely to facilitate that. It’s just that mine is a change of mindframe and a “jumping-out-the-airplane” thing. You just have to do it.

Queer people working in media and entertainment have enriched the sector, and provided more representation for fans who identify with and relate to what you’re creating as an artist. When you were growing up, did you have any queer icons you looked up to?

Definitely, I was a fan of the obvious ones like David Bowie and Freddie Mercury. I grew up loving dance and theater so there was no shortage of queer icons in that world. But I also grew up with a lot of icons who weren’t queer, I never felt outside of those people being references or inspiration for what I do. I never let the fact that I was gay define anything about me as an artist. Of course it’s enriched me in lots of ways, but I never let it be a barrier.

Now that you have this platform and visibility, how do you hope you can influence a younger generation of LGBTQ fans through your music?

It’s really lovely when I hear from young queer or trans people that tell me I represent something for them in country music that they never thought was there, or that they never felt a part of. If I can be that for someone, then I feel completely honored and thrilled by that. I hope that people feel welcome to express themselves and be a part of anything that they feel they want to be a part of, and not feel like the color of their skin or their gender, sexual orientation, or anything else should limit them. I think as marginalized people we tend to have to stand on the sidelines and be a fan from a distance or feel like maybe we don’t belong. I hope it inspires people to take up more room and get on and be a part of it because it is part of them, it’s already part of them, and there’s no invitation needed.

You’ve mentioned in previous interviews the landscape of country music is diversifying to include many new types of sounds and voices. How important is it to you to expand the genre and/or to receive acceptance from the mainstream country music industry?

I think it’s important to me in the sense that country music has always been diverse and there’s always been people of color making country music, there’s always been gay people making country music. Unfortunately, those things haven’t been able to be very visible. So I think it’s been a long time coming now that those different perspectives in country music are visible. I think it’s happening quite quickly now, and those walls put up by industry people in mainstream country music are starting to crumble. We’re getting a lot of weird new voices in country music, some have always been there, but they’re starting to creep through the cracks now. I think that’s great because it’ll just start ending the stigma about who country music is for.

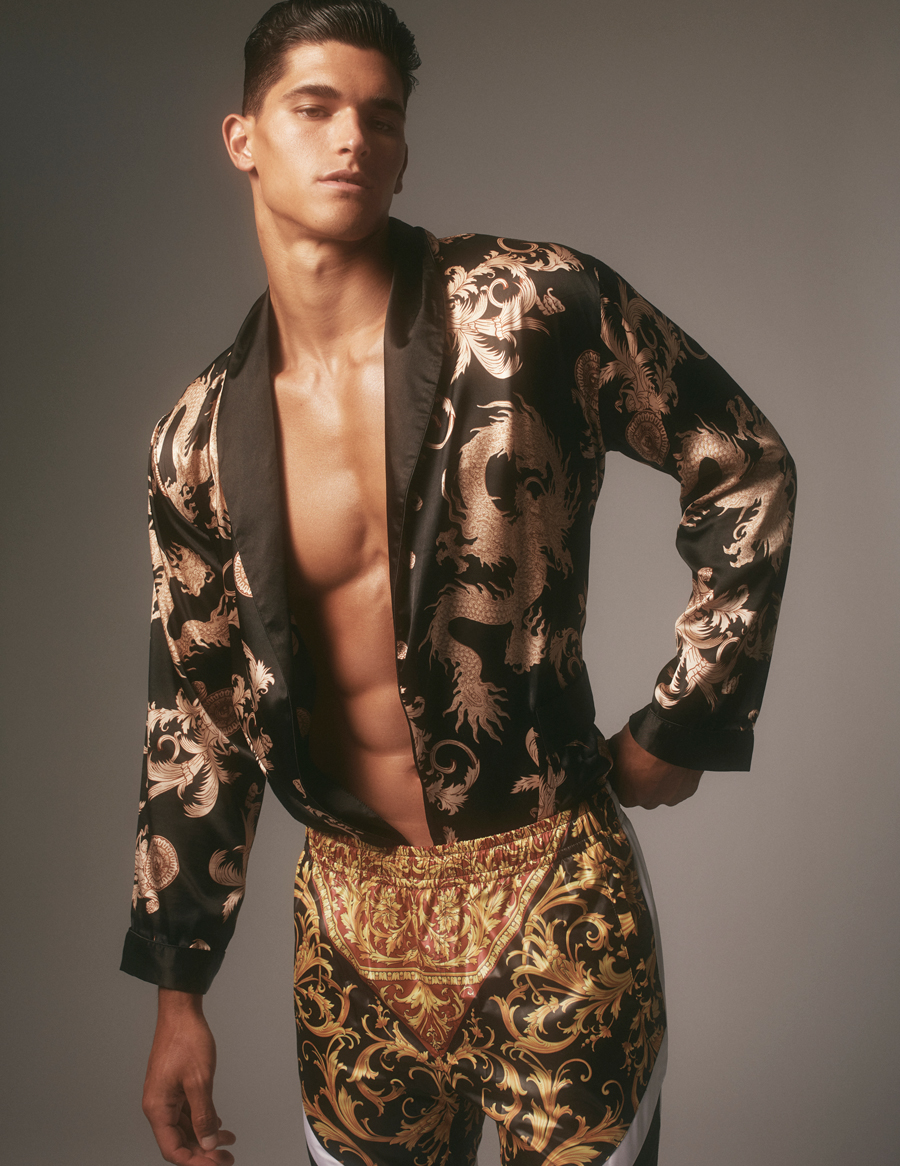

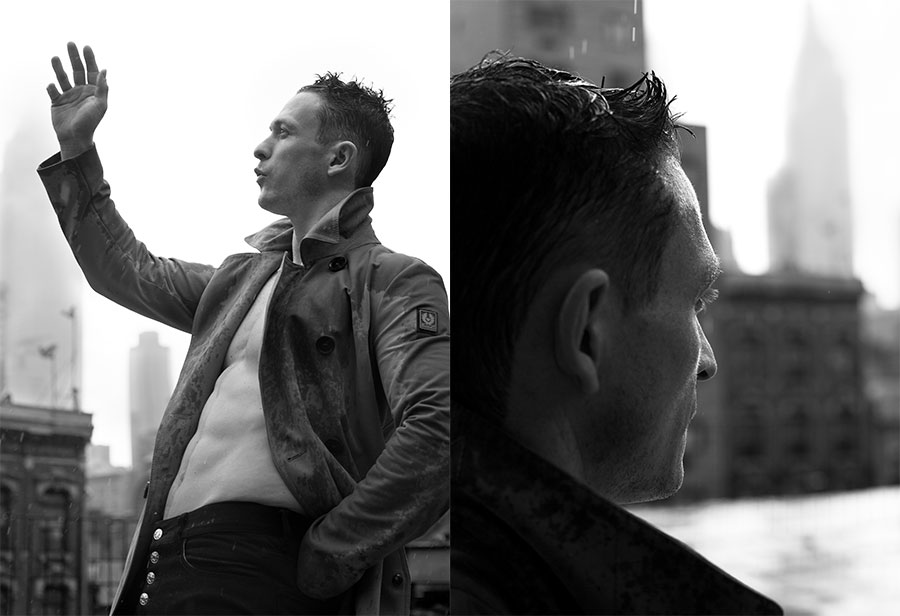

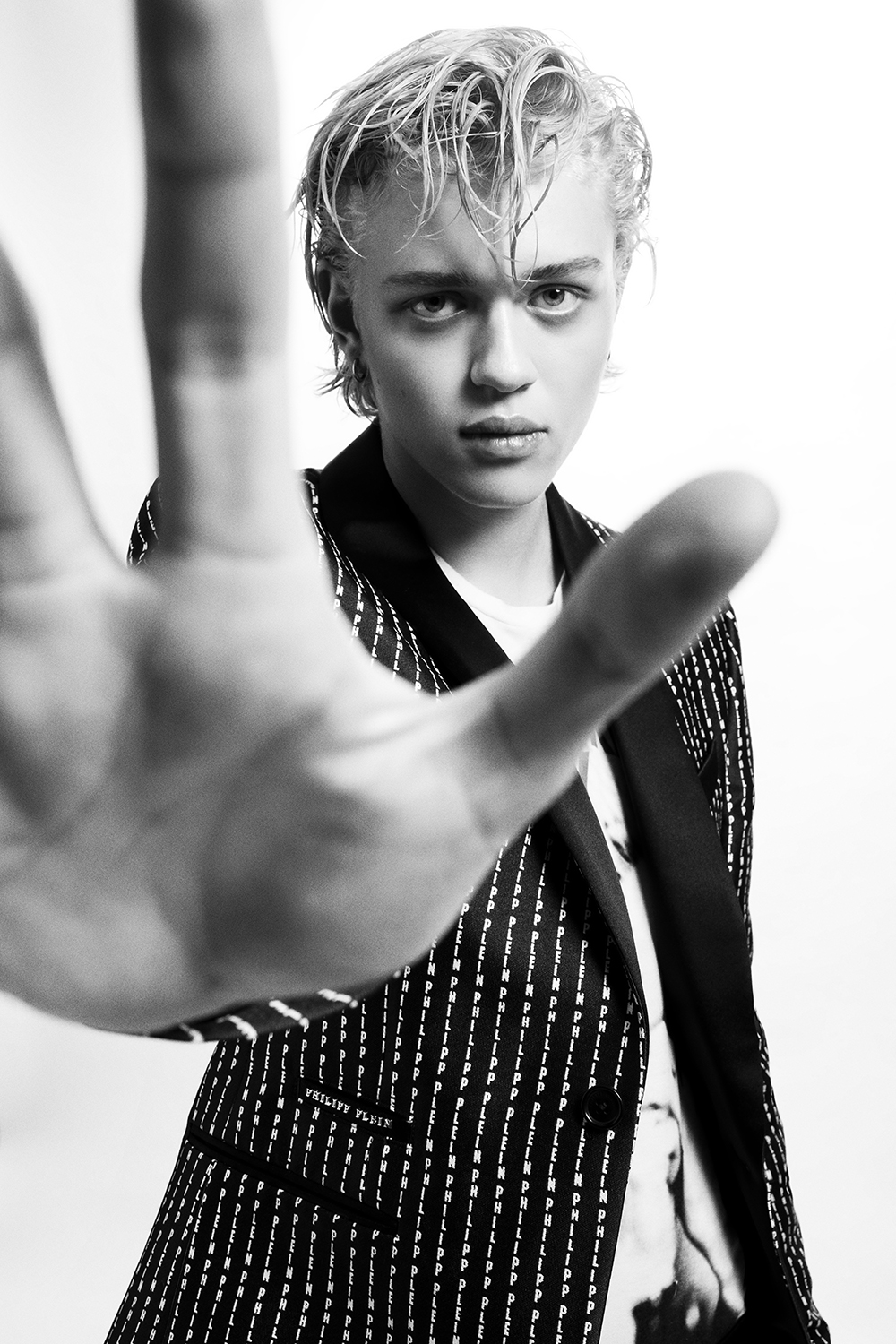

Shirt, Coat, Pants, Boxer Briefs: Versace, Hat: Stetson, Gloves: Lincoln, Boots: Star Boots

You’ve talked about your mask as having dual-purpose: an element of showmanship and a tool that allows you to be more raw / exposed as an artist. How did you arrive at the mask? Did you create the first one or did you work with a stylist or designer to engineer the look?

It’s all me and I make them. I think it was just my version of following in the footsteps of many country performers who had bold, camp, flamboyant visual imagery to their performance. There’s a huge lineage of that and a lot of them are very straight, conservative people in country music that would wear bedazzled rhinestone suits. Dolly Parton would wear 3-foot high wigs. It’s all in that sphere, so I’m definitely not the first person to do it. Maybe for newer country musicians it’s not as common, but that’s basically where I’m coming from.

Do you connect more with your audience because of the mask?

I think so. I think it eliminates a certain amount of pretense. I think it destroys the mask that people walk around wearing everyday, which you know, isn’t a real necessarily mask. I think it eliminates a lot of bullshit especially. It’s the same as when people feel so comfortable around a drag queen or someone like that. Something about it just puts people at ease and makes them feel like they can be comfortable and be themselves. That’s what I experience in my shows with people and they all look like they’re really connected to the performance because of it I think.

Jacket from Screaming Mimi’s Vintage, Pants: Gucci, Hat: Stetson, Gloves: Maison Fabre, Boots:Off-White, Necklace: His own

You’ve been described as a musical “outlaw” and the mask reinforces this idea. In a way it’s reminiscent of a bandana-wearing bandit hero, like Zorro or the Lone Ranger. Do you think your audience responds or relates to it because of this idea of a hero-like figure?

I think so. I think people project a lot of different interpretations of it. That’s what I love about it and that’s also why I hate to talk too much about it because I don’t want to put too much narrative on top of it. I actually like that people can have their own interpretation of it. Some people look at it and think of the Lone Ranger and then some people look at it and see an S&M mask and it’s like, well that tells me a lot about that person. That’s what I like about it—that it is open for interpretation. And it allows people to be involved in what I do. For a fan to feel involved in it and that they can get a piece of that too, then that is what you could only hope for as an artist. People not only enjoy what you do but they’re invested and they feel a part of it. Some of the musicians, visual artists, actors, filmmakers, and authors that I still respect to this day are people that made me feel like I had some ownership of what they did as well.

The dichotomy of being an openly queer artist while hiding your physical features is a striking juxtaposition. Do you think you’ll ever “out” yourself physically from under the mask?

I don’t know. To me I don’t feel like I’m hiding at all. I feel like I wear my heart on my sleeve in a lot of ways. We’ll see what that evolution is. At the moment I’m really happy just doing my thing as I’m doing it.

Your music explores the nostalgia of Americana and its sound. It’s a staple source of inspiration for many iconic popular country and folk-rock ballads. Having such a diverse international background, what inspires you most about Americana?

I think it’s the seemingly normality. I think Americana as we’ve been told to believe is apple pie. It’s very clean and neat with a picket fence. The reality of American culture is far weirder and darker than that at times. It involves a lot of trauma and craziness. I think that’s the part of Americana that I find far more fascinating. I think that is the real Americana. I always talk about how I love motels because the idea of this like chic version of a hotel that is on a highway and it’s very cheap, there’s no questions asked and sometimes people live in them for months at a time. That doesn’t even exist anywhere else in the world and that’s like a whole culture of America that is of its own. I find that really fascinating and I think the people and characters that inhabit those kind of worlds are really interesting.

Shirt from Screaming Mimi’s Vintage, Vest: Gucci, Jeans: R13, Hat: Stetson, Gloves: Agnelle, Belt: Kippys, Boots: Fyre

So many artists reinvent themselves over the course of their career. With your musical training, background, and musical influences being so diverse – Do you think you’ll stay exclusively a country music artist or begin to incorporate other sounds into your work?

I think I’ve always been kind of incorporating different sounds into it, but at heart I’m a country boy and I’ll continue to be a country musician. I think I’ll always try and push that to not leave it strictly in what other people’s idea of what country music is.

That darkness has, in recent times, become much more visible. Concentration camps have quickly become a new norm in America under the current administration. Trans rights have been challenged through rollbacks on protection for military service and healthcare provisions under the Affordable Care Act. Do you foresee this escalating its target on more LGBTQ+ people?

Unfortunately, I think I do. I think across the board not just with LGBTQ people, but also people of color, women, and marginalized people. In America we’ve been allowed to believe that things are changing but at the root of it nothing has been changing. Now that’s become more obvious to us and I think, strangely, not to sound flippant about it, but I believe that’s where this resurgence of cowboy aesthetic has actually come into play in our culture. To me being a cowboy has nothing to do with wearing a cowboy hat or being a rancher and roping cows or charging steers. I think being a cowboy is being someone who is intrinsically, innately on the outside of things and given a bad rap, maybe getting the short end of the straw, and forced to live on the outskirts of town. But instead of letting that be a negative, it’s about finding the power within that and the adventure and the freedom. The idea of getting on a horse and riding into the sunset, I think that sounds really beautiful for people like us right now where we can find our posse of rebels and cowboys, make our own rules and essentially live as outlaws. Those all sound like motifs and pastiche kind of ideas, but they do hold bearing. I think that is what being marginalized is about. It’s about not assimilating to the status quo, finding our community, our power, and charging ahead in the face of whatever. I think it’s a powerful thing, and I actually do believe that is why we’re seeing so much cowboy imagery in fashion and sub-culture and because there is something adventurous and powerful about that.

You alluded to this earlier in our conversation and in previous interviews drawn upon similarities between the Old West and the present state of affairs today saying, “We lived in a recent time when we hoped everything was going to be okay, that the powers that be were going to sort it out. But now everyone’s fending for themselves because they’re disappointed. Everyone’s on their own horse, doing their own thing.” So, if we’re all on our own horses, do you think we are equipped to become a calvary for change?

I think so. I do like to believe that. Listen, I have lived in countries other than America where I have seen, witnessed, had to live through massive social change on a really huge scale. I think it comes through perseverance and I think it comes to sticking to your guns and not swaying from who you are and what you believe in. I do believe that is powerful enough to make change because I’ve seen it happen. I think it’s time for all our posse, to find our community, and do exactly that—form a calvary and stick to who we are in the face of no matter what for change.